A VIEW FROM THE COURTROOM

The court of art criticism is in session

on Oct 12, 2022 at 7:32 pm

A View from the Courtroom is an occasional series offering an inside look at oral arguments and opinion announcements unfolding in real time.

This week has felt very cultured at the court. Despite the earthiness of Tuesday’s case about pig farming, I found myself revisiting, for one preview I wrote, literary works by Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, and Norman Mailer, addressing stock yards and meat processing in the 20th century. (I also consulted the most recent issue of Quarterly Hogs and Pigs, a periodical published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.)

Today, the court’s attention will be on the often glamorous worlds of Pop Art, rock photography, and glossy magazines. It will veer into “Lord of the Rings,” “Jaws,” “Mork and Mindy,” and “The Jeffersons.” And one of the lawyers participating today will try to bury a beloved television producer and social activist. But I’m getting a little ahead of myself.

It has become more clear, during this second week of the public’s return to the courtroom after pandemic-required measures, that there are some limitations on the number of people being let in. The public gallery has several rows that have been kept empty. And the seats in the bar section are spaced apart a bit more than before the pandemic, and it appears that the capacity of that section may have been reduced by one whole row.

A few regular members of the Supreme Court specialty bar are here. Kannon Shanmugam of Paul Weiss is in the bar section, while Michael Dreeben, a former deputy U.S. solicitor general now with O’Melveny and Georgetown University Law Center, takes a seat in the public gallery. And Paul Clement, now of the boutique firm Clement & Murphy, is seated at the second case counsel table to await argument in Helix Energy Solutions Group v. Hewitt.

When the justices take the bench, Chief Justice John Roberts proceeds with the recently restored practice of in-courtroom bar admissions. “The clerk — the deputy clerk” will entertain motions for admission to the bar, he says, catching himself because Clerk Scott Harris is absent today, and Deputy Clerk Laurie Wood is fulfilling his courtroom duties.

And then it is on to the argument in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Inc. v. Goldsmith, a copyright dispute over a photograph of the musician Prince. Rock photographer Lynn Goldsmith, who took the photo of a vulnerable and sensitive-looking Prince in 1981, when he was still an up-and-coming musical artist, is in the second row of the public gallery today.

When Prince shot to stardom by 1984 with his “Purple Rain” album, Vanity Fair licensed Goldsmith’s photo for use as an artist’s reference for an illustration to accompany a profile of Prince. The artist they engaged was Andy Warhol, famous for his paintings of Campbell’s Soup cans and celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe.

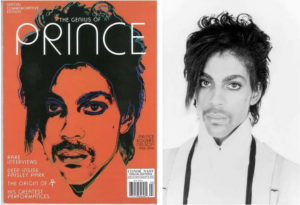

Warhol cropped and silkscreened Goldsmith’s photo into a series of 16 images of Prince, now known as the Prince series. One of those — “Purple Prince” — ran with the Vanity Fair article. Another, “Orange Prince,” ran on the cover of a commemorative magazine that publisher Condé Nast issued after Prince’s death in 2016.

Left: A 2016 Vanity Fair cover featuring Andy Warhol’s image of Prince. Right: Lynn Goldsmith’s 1981 photograph of Prince, which was a basis for Warhol’s image. (Source: court documents)

Goldsmith objected to the 2016 use as a violation of her copyright, though the New York City-based Andy Warhol Foundation filed suit pre-emptively to seek a declaration that the entire Prince series was a fair use under copyright law because, according to the foundation, Warhol’s images transformed Goldsmith’s photo into a new work with a different meaning or message.

Roman Martinez, representing the foundation, tells the court that “the stakes for artistic expression in this case are high. A ruling for Goldsmith would strip protection not just from the Prince series but from countless works of modern and contemporary art. It would make it illegal for artists, museums, galleries, and collectors to display, sell, profit from, maybe even possess a significant quantity of works. It would also chill the creation of new art by established and up-and-coming artists alike.”

Goldsmith is shaking her head as Martinez speaks. Throughout the argument, she will visibly show her disagreement or nod in agreement with various points made by the lawyers and justices. Elsewhere in the courtroom are several representatives of the foundation—President Joel Wachs, Chair Paul Wa, and Chief Financial Officer and Treasurer KC Maurer. I can’t see whether they are shaking their heads or not.

The justices press Martinez about what it takes to create a derivative work that falls under his test for transformation.

The chief justice wonders about taking the Goldsmith photo and putting a smile on Prince’s face.

“The message is: Prince can be happy,” Roberts says. “Prince should be happy. Is that enough of a transformation? The message is different.” (Martinez says it would depend on the degree of transformation in meaning or message.)

Justice Clarence Thomas tries to ask Martinez a question about transforming Warhol’s “Orange Prince” image into a “Go Orange” message in support of Syracuse University.

“Let’s say that I’m both a Prince fan, which I was in the ’80s …” Thomas says, before Justice Elena Kagan interrupts him.

“No longer?” she says.

“Well,” he says to laughter, “so only on Thursday night.”

Several questions for both lawyers concern book-to-movie adaptations, which generally involve licensing. Some justices wonder whether Martinez’s test would “eviscerate” a key analytical factor for fair use under the Copyright Act.

“If a work is derivative, like ‘Lord of the Rings,’ you know, book to movie, is your answer just like, well, sure, that’s a new meaning or message, it’s transformative, so all that matters is [the Copyright Act’s factor on effects on the market]?” Justice Amy Coney Barrett asks.

When Martinez suggests the “Lord of the Rings” movies are not fundamentally different from the J.R.R. Tolkien works, Barrett seems surprised.

“The movie?” she says.

“I would probably have to learn more and read the books and see the movies to give you a definitive judgment on that,” Martinez says, to laughter in the courtroom.

When Lisa Blatt moves to the lectern to argue on behalf of Goldsmith, she makes it clear that she believes the Warhol Foundation benefited in the district court, where the foundation won, from Warhol’s reputation as a Pop Art icon.

The foundation says that “Warhol is a creative genius who imbued other people’s art with his own distinctive style,” Blatt says. “But Spielberg did the same for films and Jimi Hendrix for music. Those giants still needed licenses. Even Warhol followed the rules. When he did not take a picture himself, he paid the photographer. His foundation just failed to do so here.”

Her past-tense treatment of the still-working Steven Spielberg is a mere foreshadowing of a more, um, grave error she will make a little later.

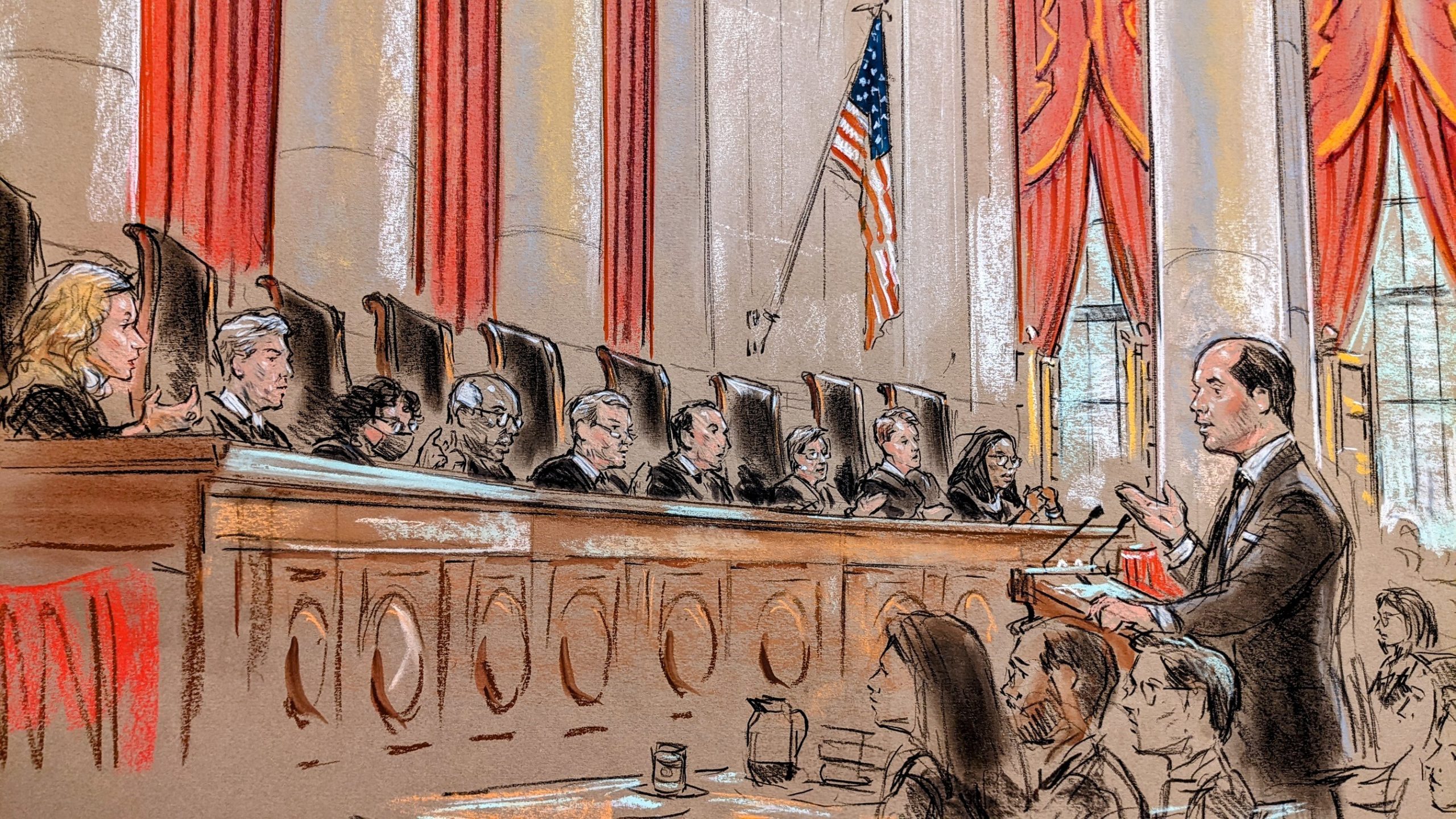

Lisa Blatt argues for photographer Lynn Goldsmith. (William Hennessy)

Sometime after Blatt refers to a page of the 2nd Circuit decision that “they’re yakking about,” Justice Samuel Alito picks up on her word choice. He asks about the 2nd Circuit’s suggestion that a district judge in a copyright case “should not assume the role of art critic.”

“What do you think the 2nd Circuit meant when it yakked about art critics, about judges not being art critics?” Alito says. “Was the point that … a person who knows nothing about either of the works of art is supposed to determine whether they seem different?”

Blatt’s answer includes a quick shift to more book-to-movie and -TV adaptations.

“Was the character in ‘Jaws,’ the book, different than the way the sheriff was depicted in the movie?” she says, before turning to “The Shining.” “We know Stephen King had a very specific view of who Jack was. It was basically him and it was a tragedy, and we know what Stanley Kubrick did to it. He said, I don’t like your Jack. I’m going to do my Jack, who’s a horror film.”

She has TV spinoffs on her mind as well, as part of her argument that such book-to-movie or TV show-to-spinoff adaptations might not require licensing under the Warhol Foundation’s test. Her references are mostly from the 1970s, including the perhaps little-remembered fact that “Mork and Mindy” was a spinoff of “Happy Days.” And then there were the more socially relevant shows of that era.

“Take ‘All in the Family,’” Blatt says. “Norman Lear would be turning over in his grave right now. He had more spinoffs than any show in American history. ‘The Jeffersons’ was about a prospering African American family who lived on the East Side. ‘All in the Family’ was about a white bigot living in Queens who couldn’t keep up with society.”

Blatt evidently did not watch the 90-minute special on ABC in August celebrating Lear’s 100th birthday. He was born July 27, 1922, and is still very much alive. On the special, he discussed the idea behind spinning off “The Jeffersons” from “All in the Family.”

No one on the court seems to have watched the special, either, as none of them call attention to Blatt’s miscue.

Still, Blatt, who was joined in the argument by assistant to the U.S. solicitor general Yaira Dubin, appears to make headway with at least some of the justices, and she seeks to allay the fears of art museums that they would face greater copyright risks under Goldsmith’s view of the case.

“If the poster child for museums is Andy Warhol, let them tell you what Andy Warhols they’re worried about,” she says. “He took all the pictures of the famous ones or he got a license.”

“But maybe there’s a different point about museums,” says Justice Kagan, who seems more sympathetic to Martinez’s arguments. “And the point is why do museums show Andy Warhol? They show Andy Warhol because he was a transformative artist because he took a bunch of photographs and he made them mean something completely different. And people look at Elvis and people look at Marilyn Monroe or Elizabeth Taylor and Prince, and they say this has an entirely different message from the thing that started it all off. And that’s why he’s hanging up on those museums.”