Empirical SCOTUS: How the justices and advocates spent their speaking time during the May arguments

on May 29, 2020 at 3:32 pm

Editor’s note: This is the third post in a series analyzing the Supreme Court’s telephonic oral arguments with live audio instituted due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Supreme Court heard some of the most important cases of the term in a month when there almost were no arguments at all. The court canceled its March and April sittings due to COVID-19. With flexible ingenuity, it then rescheduled 10 arguments for May, which was the first time the court has had anything near a full May sitting since OT 1968 — Chief Justice Earl Warren’s final year on the court. Some of the most significant cases the court heard in May 2020 involved issues like the potential release of President Donald Trump’s tax returns and how states may deal with members of the Electoral College who do not vote according to the wishes of the majority of their state’s voters.

Much was said in these arguments, and over two prior posts (here and here) I examined both how these remote, telephonic, live-streamed arguments compared to past arguments this term and how the procedures in this new argument format led to unique forms of participation from the justices. The last post in particular focused on how Chief Justice John Roberts allocated time to the justices in a predominantly uniform manner. This post looks at how the justices and attorneys used their speaking time.

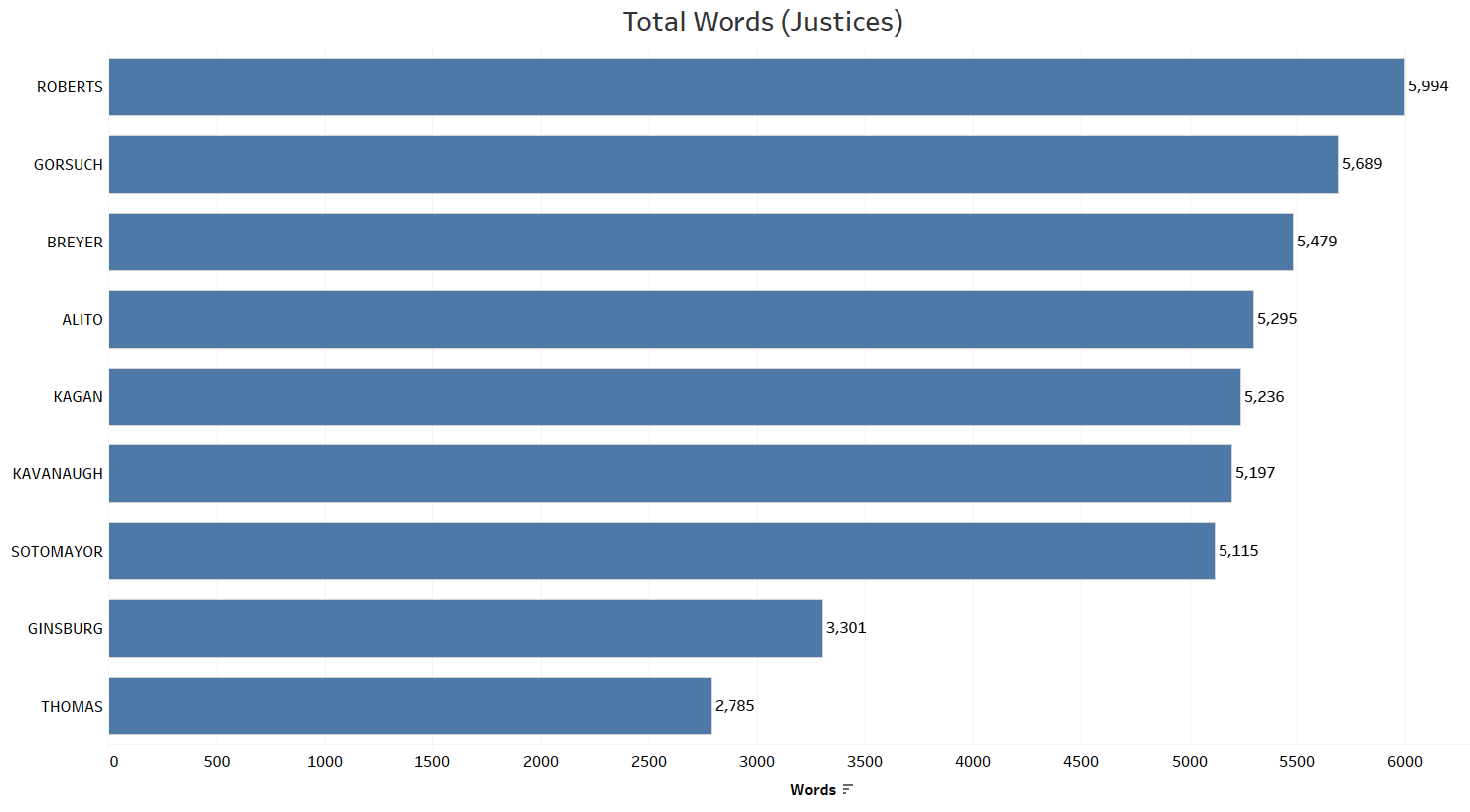

The oral argument transcripts provide data on how talkative the justices and advocates were as well as what was said. Looking first at the justices, the figure below examines the total words spoken for each justice across all 10 arguments in May. (Note that Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor were recused from one argument apiece, which ultimately diminished their word counts; Roberts’ counts include his role as timekeeper, so his high word count should be taken with a grain of salt.)

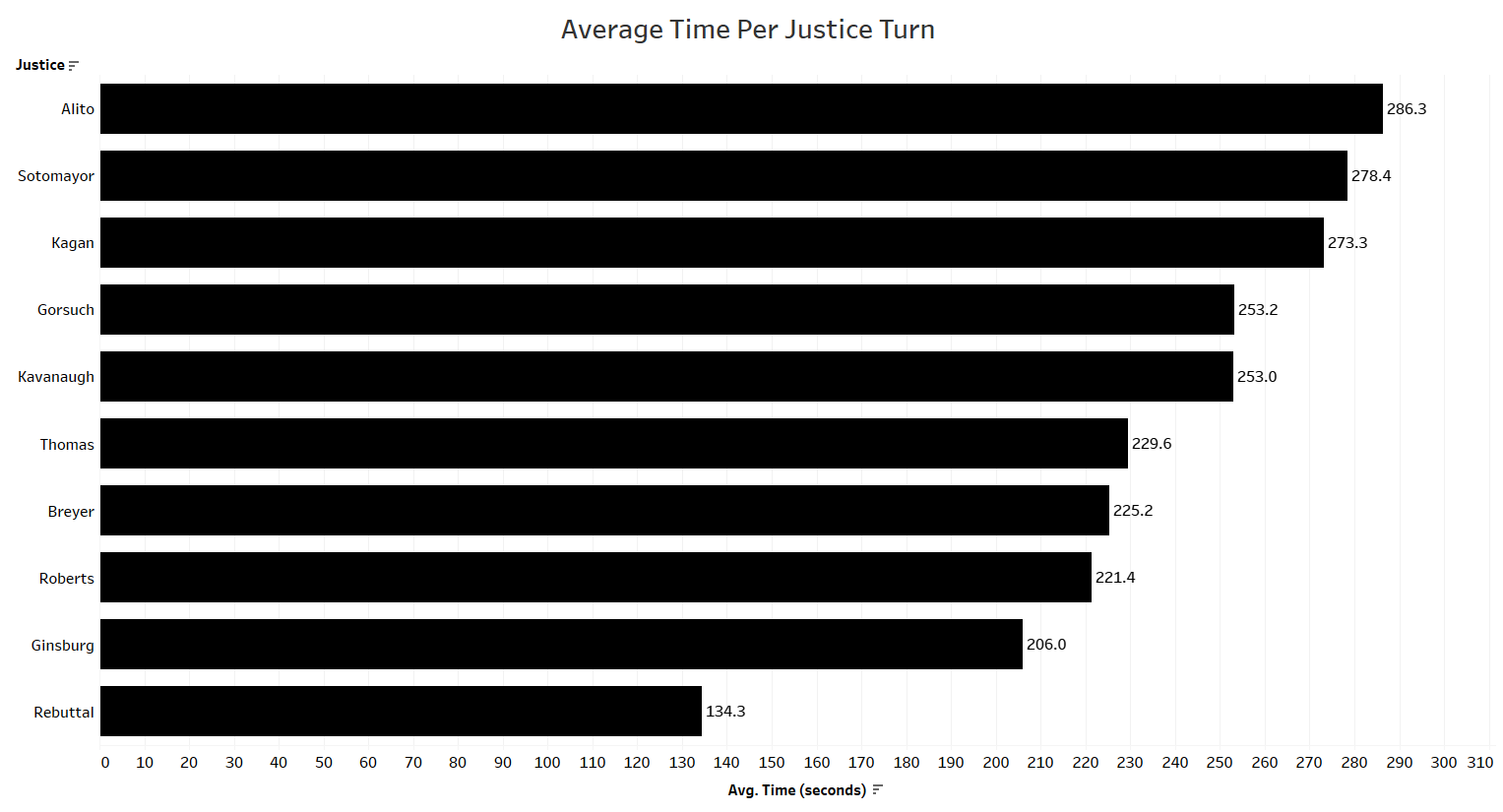

The word count totals are especially interesting because they differ from the time allotment list, which was led by Justice Samuel Alito, followed by Sotomayor and Kagan.

This shows that justices are able to articulate different levels of information in varying amounts of time and that time allotment is not the only way to analyze the relative participation of the justices in these arguments.

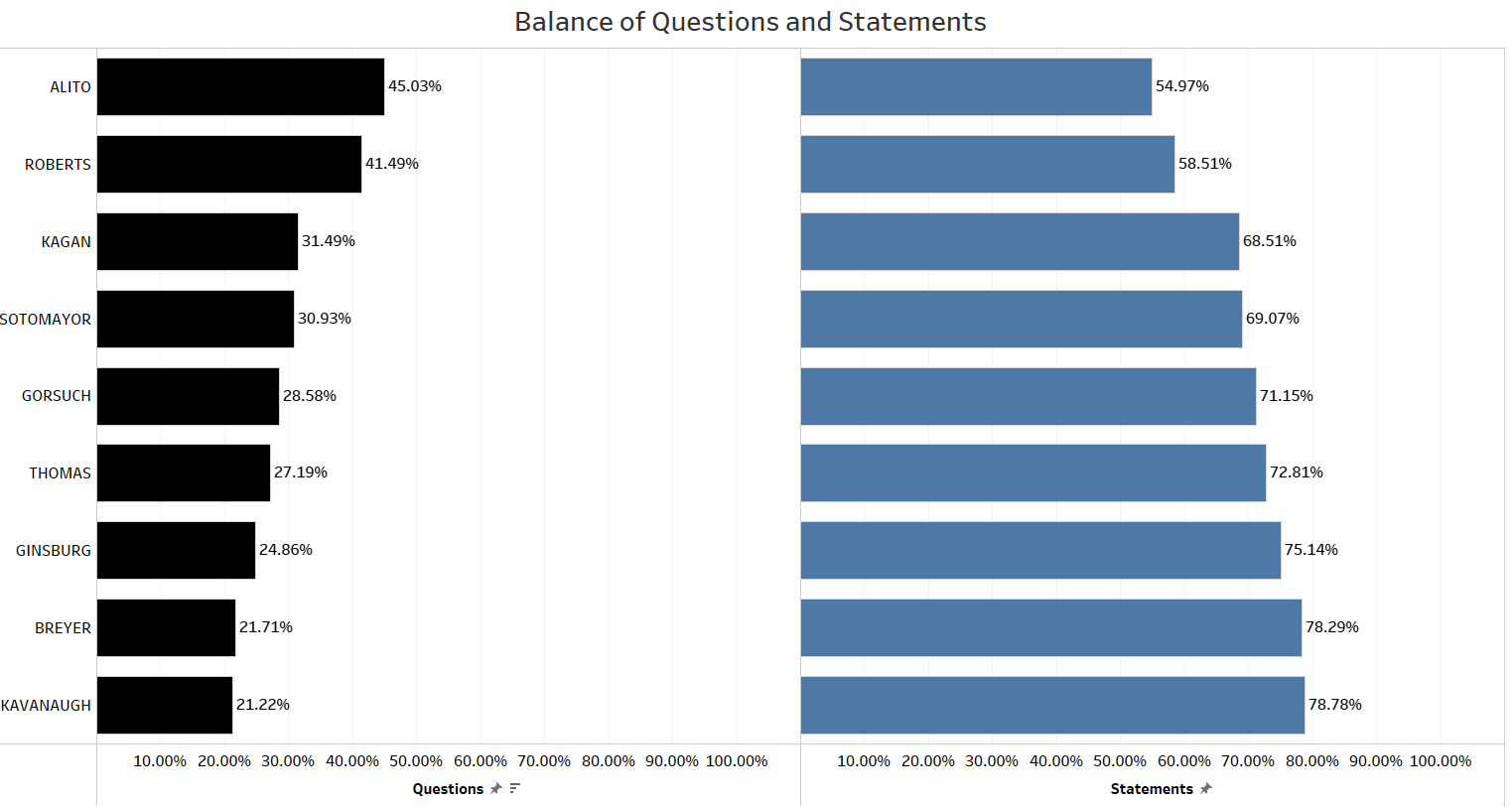

Next, looking at the balance of questions (sentences ending with question marks) and statements (sentences ending with periods), we can observe how the justices chose to spend the balance of their time with the attorneys.

Alito asked the highest percentage of questions relative to statements, with Roberts only a few percentage points behind. Justices Stephen Breyer and Brett Kavanaugh predominantly spoke to the attorneys, each using only slightly over 21 percent of their time asking questions.

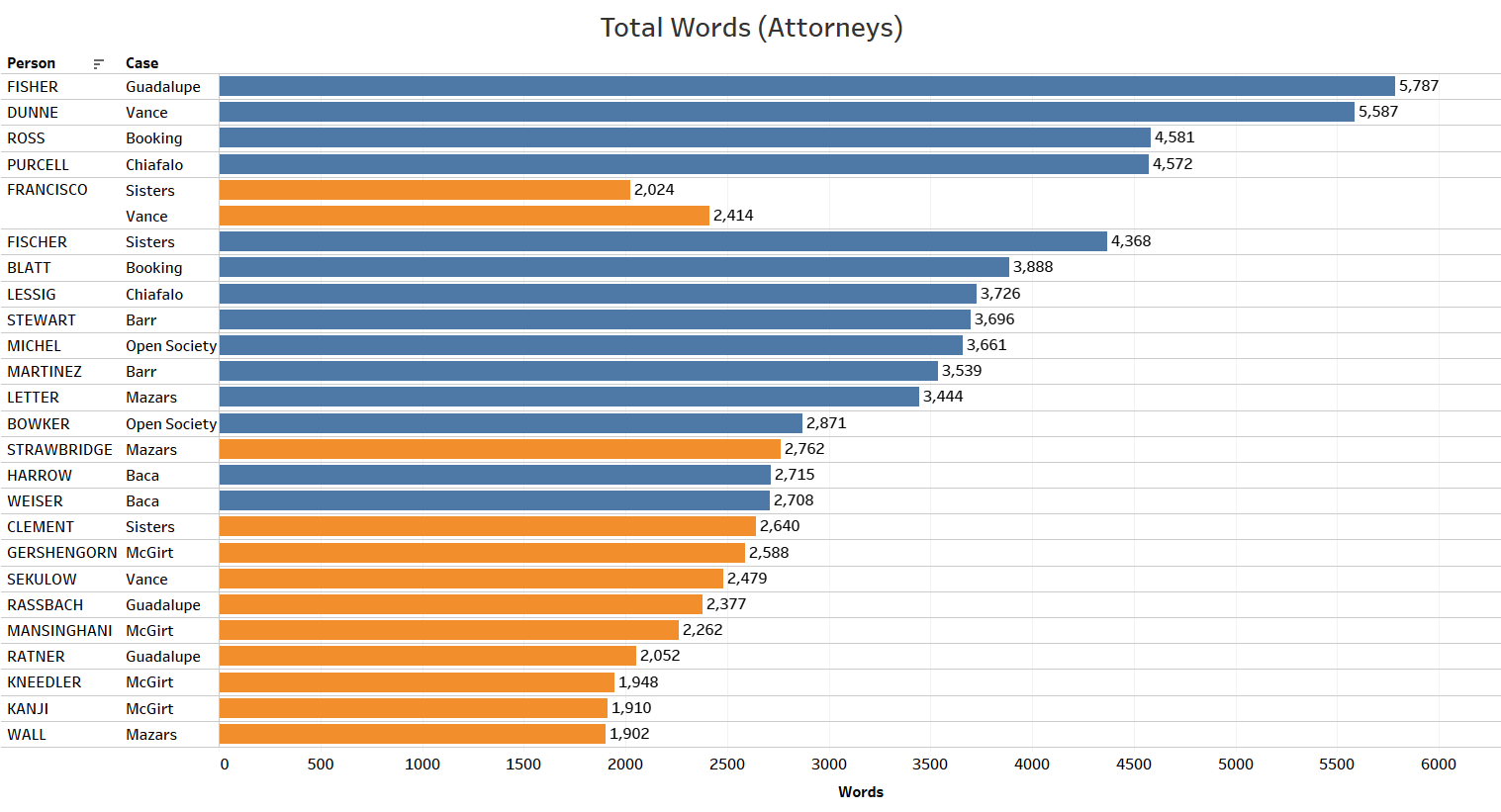

As for the attorneys, there was quite a large disparity in their amount of relative speech. A main factor in the disparity was that some attorneys were one of two who argued for the same side in a case. To differentiate these attorneys in the figure below, attorneys with orange bars were one of two attorneys for a side in a case, while attorneys with blue bars were the sole attorneys who argued for a side.

Solicitor General Noel Francisco was the only attorney to argue twice during this sitting — in Trump v. Vance and Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania, both times as one of two attorneys for the petitioners. When combined, Francisco’s total words spoken place him as the fifth-most talkative attorney. Jeff Fisher, representing the respondents in Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru, spoke the most of the attorneys during the May sitting, followed closely behind by Carey Dunne, who represented the respondents in the Vance case. For some context, only four attorneys spoke 4,000 or more words in an argument across the entire 2017 Supreme Court term. Fisher had the second largest word count that term, with 4,184 words in Koons v. United States, placing him only one word behind Adam Unikowsky, who spoke 4,185 words in Sveen v. Melin.

In total, Roberts and Kagan both spoke most in three arguments each, with Sotomayor speaking most in two arguments, and Kavanaugh and Gorsuch speaking most in one argument each. If we assume that Roberts spoke at least 50 words per argument as timekeeper, then Roberts only topped the speaking list in one argument (Vance), while Gorsuch moves into the top spot in three arguments. At the other end of the spectrum, Justice Clarence Thomas spoke least in seven of the arguments from the May sitting, while Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg spoke least in the other three.