Empirical SCOTUS: Results from the court’s experiment with a new oral argument format

Editor’s note: This is the second post in a series analyzing the Supreme Court’s telephonic oral arguments with live audio instituted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Data for this project was provided by Oyez, a free law project by Justia and the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School. Kalvis Golde and Katie Bart both provided invaluable assistance in aggregating data for this post.

We recently witnessed what was likely the biggest experiment in the history of Supreme Court oral arguments. As former Chief Justice William Rehnquist described in his essay looking at shifts in the focus of Supreme Court advocacy from oral arguments to the briefs, the biggest changes in the structure of oral arguments historically had to do with the time allotted to individual arguments. Now, even though potentially ephemeral, the new structure implemented in May included unprecedented changes to the argument format. The three main alterations were that the arguments occurred remotely, so for the first time during arguments the justices were not in the same room with the advocates and one another; that the court used an ordering mechanism whereby the justices asked questions individually and in order of seniority; and, critically, that the justices were limited in the time they could question.

With this new ordering mechanism, Chief Justice John Roberts took on a new role as timekeeper. In this role, Roberts noted when it was time to shift between each justice’s turn questioning the advocate. This did not always move smoothly, because certain justices were hampered by still-activated mute buttons that prevented them from seamlessly assuming the role of questioner. Transitions between questioning justices also were made difficult because Roberts needed to decide when was an appropriate point to end one justice’s turn and move to another.

Roberts could have granted the justices equal time, simply cutting a justice off when their time was over, but instead he attempted to let justices finish their questions. In certain instances this meant stopping an advocate or justice in the middle of a statement, and in other instances it meant allowing a justice or advocate more time to finish a question or statement after the time allotted was already complete. Beyond Roberts’ timekeeping methods, the justices, knowing they were limited in their individual time to interact with the advocates, needed to decide how to balance their time between questions and answers. This post examines how time was kept and spent during the May oral argument sitting.

Methods

Because these arguments were different in kind from previous arguments, new methods were used to track speech across justices than in prior posts. To track time, we used Oyez’s time-stamped oral argument data. We initially pulled the JavaScript Object Notation, known as JSON, text from each oral argument from the May sitting from Oyez’s repository and transformed it into spreadsheet format. The JSON data tracks each actor’s speech and the time taken for each speaking instance starting at time zero. For instance, Roberts may have said something from 0-5 seconds, then Justice Clarence Thomas from 5-7 and then an attorney from 7-10. This would tell us that Roberts spoke for five seconds, Thomas for two and the attorney for three. Using this method, we tracked the amount of time each actor spoke across each speaking turn in each of the arguments.

We then aggregated these times into three sets. The broadest set was the relative time given to the petitioner’s and respondent’s attorneys (and respective amici) during an argument. The next level was the relative amount of time spent in each justice’s turn, including time taken by the attorney and the justice. The time Roberts took interjecting to switch between justices was omitted from this measure. The most specific level was the time taken for questions and answers within each justice’s turn. Times for attorneys’ opening and closing statements were removed from justices’ individual times, because they were unrelated to any justice’s turn.

Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan were both recused from one argument apiece. They were given no time measures for these arguments.

Time by side in each case: Roberts’ decisions

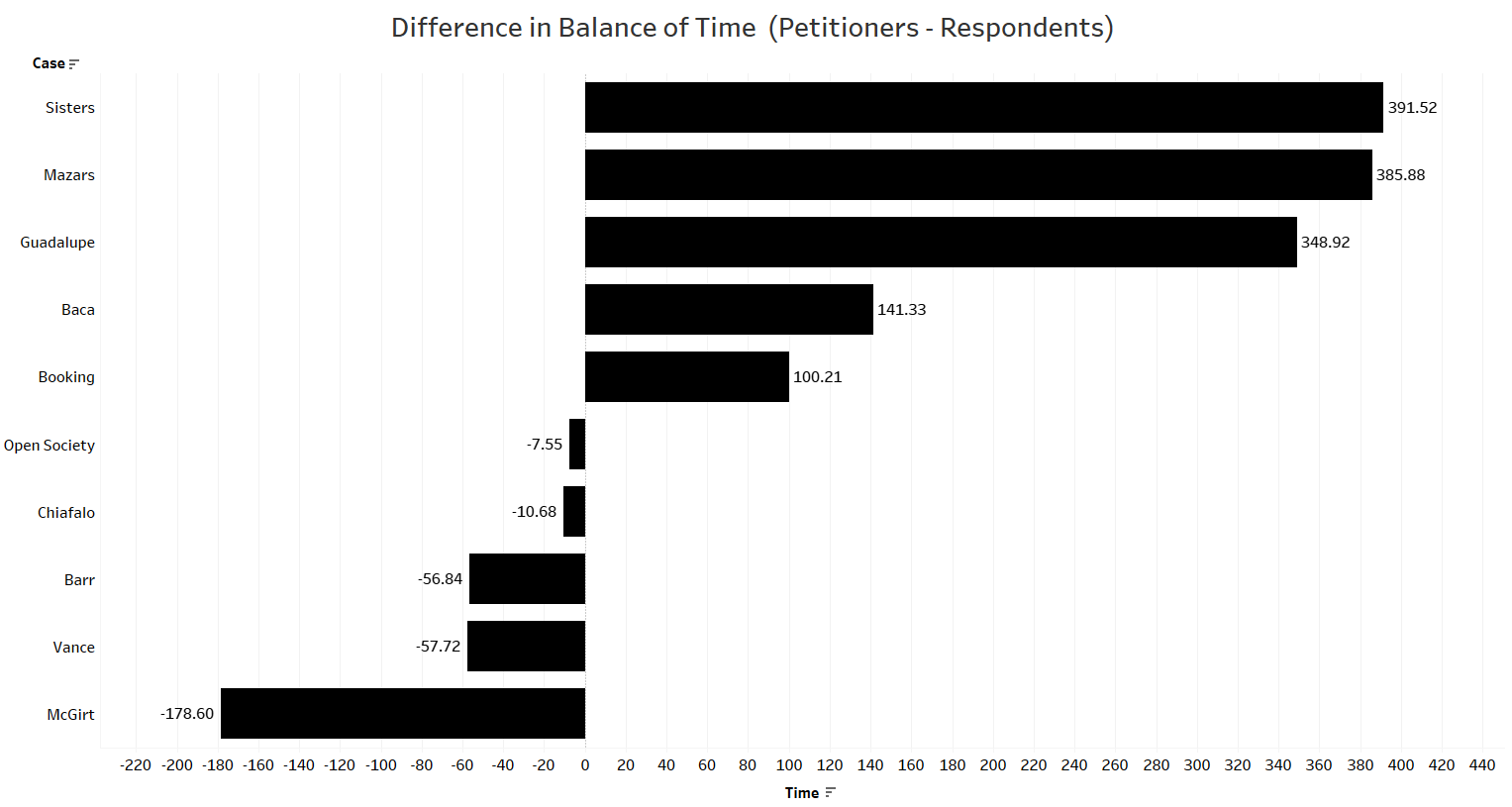

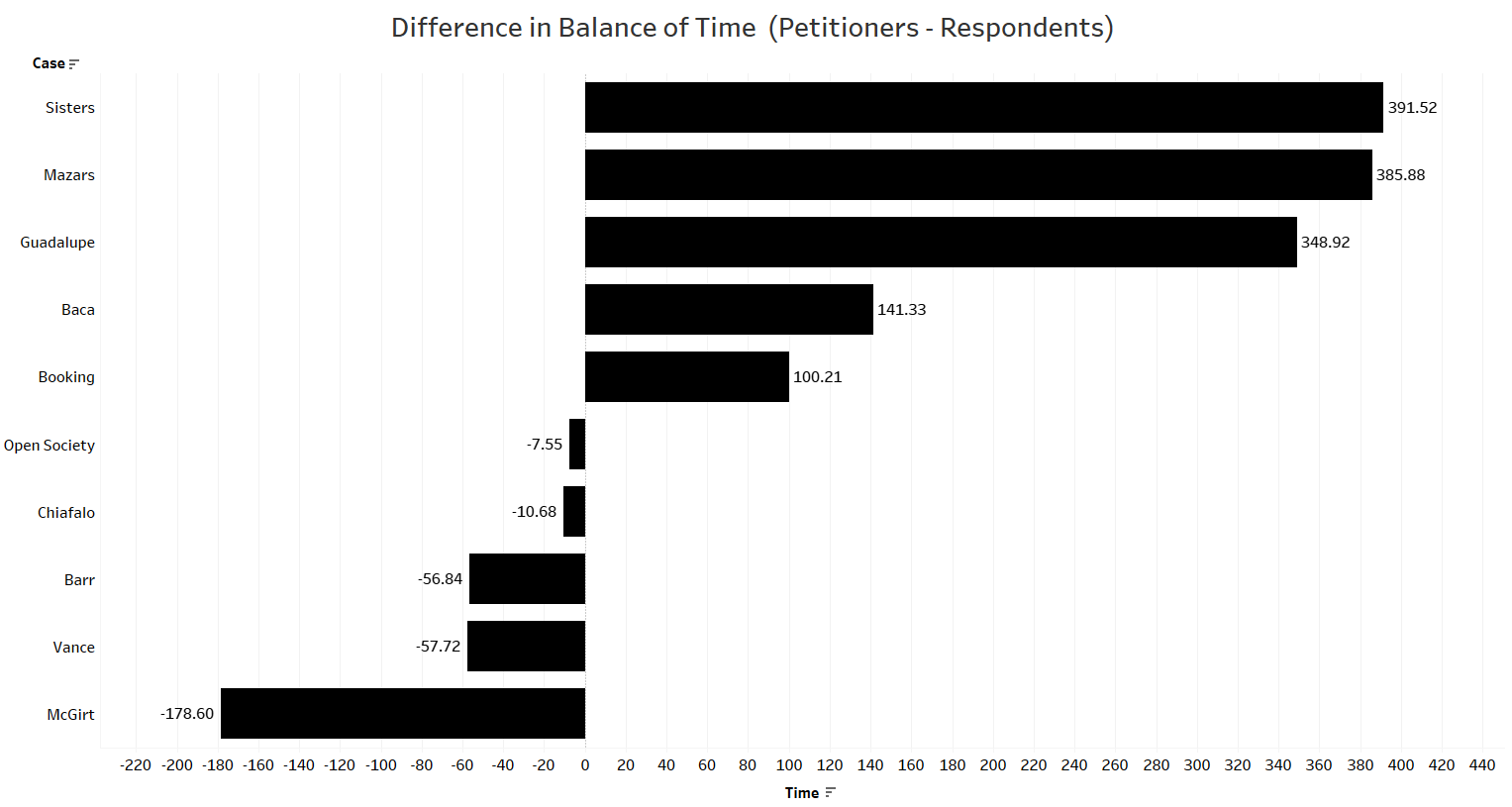

At the broadest level, Roberts had to balance the time given to the petitioners and the respondents in each case. This was complicated by the presence of multiple attorneys for particular sides in some cases. Still, for the most part, the amount of time given to each side was fairly evenly balanced. The following graph looks by case at the difference in time allotted to respondents subtracted from the time allotted to petitioners.

In three cases, one side received at least three minutes more than the other. The biggest difference in a case was in Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania, in which the petitioners were given 391 more seconds than the respondents, and there were also quite large differences in the petitioners’ favor in Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru and Trump v. Mazars. The petitioner in each of these three cases had a second arguing attorney. Although a second attorney argued on behalf of the petitioner in Trump v. Vance as well, the balance of time in Vance actually favored the respondent slightly..

Times by justice: mainly Roberts’ decisions

One major question raised by the new argument method was how equally Roberts would allot time among justices. In practice, though, this proved to be a blend of the individual justices’ choices as well as Roberts’. Roberts ended justices’ turns to transition between them on many occasions, but in certain situations, justices also either explicitly or implicitly hinted that they were through before their time was up. On these occasions, Roberts needed to make an informed decision about whether it was appropriate to move onto the next justice.

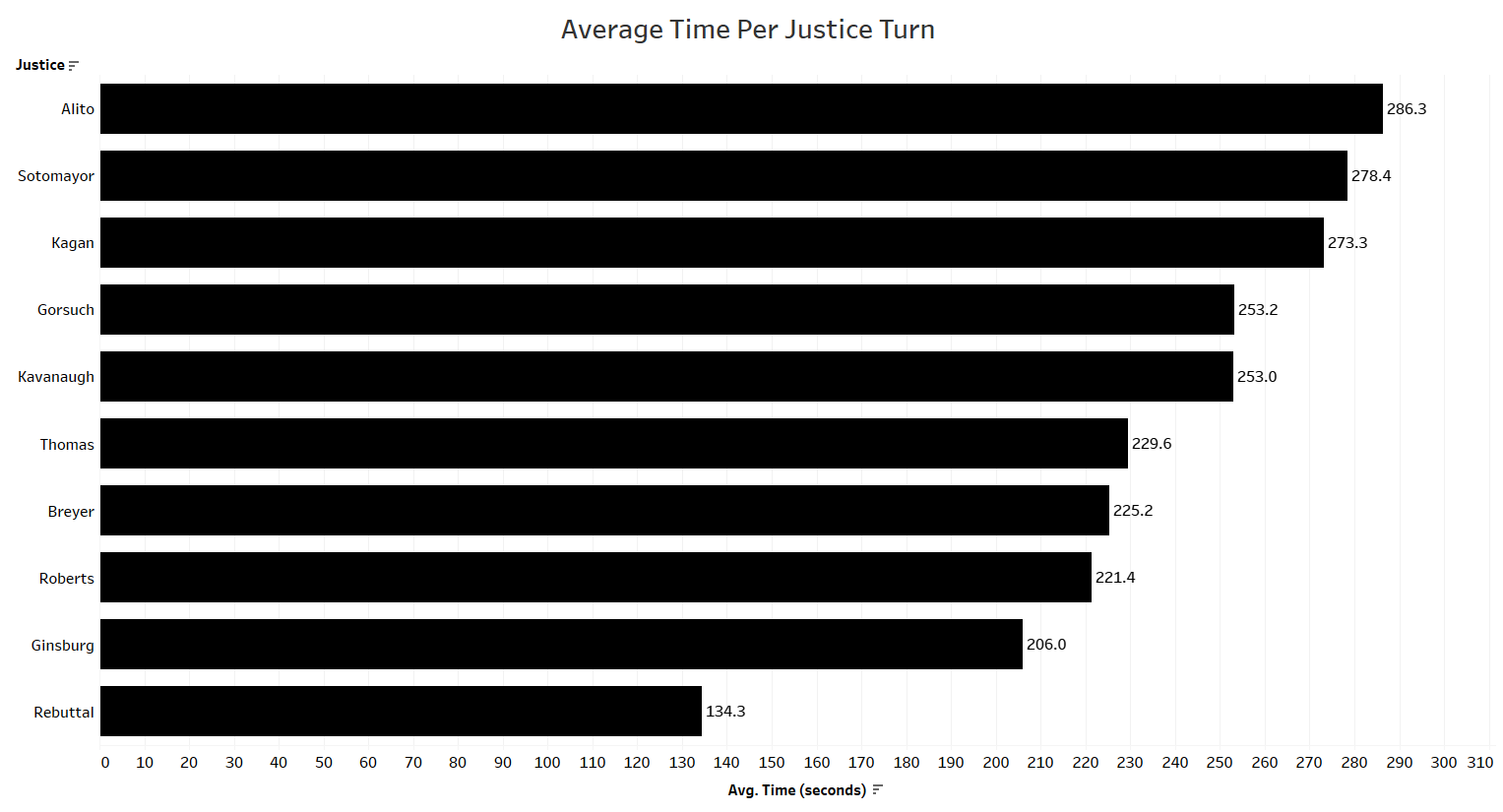

We aggregated the time spent on each justice’s turns with each attorney in each argument. We then averaged these numbers by justice. The graph below looks at the average time given to each justice by turn and is ordered from the justice who had the most time to the least. The average time for the petitioner’s rebuttal was retained as well.

Justice Samuel Alito was given the longest average time per turn, with 286.3 seconds. Sotomayor had the second-most time per turn, with 278.4 seconds. Thomas, who only spoke twice in oral arguments prior to this sitting over the past decade, took each talking turn he was given. His average was right in the middle of the justices, with 229.6 seconds per turn. Roberts, who led the proceedings, took the second-least amount of time on average, with 221.4 seconds (discounting any time Roberts spent in his role as timekeeper). Roberts took only 15.4 seconds on average more than Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who took the least amount of speaking time of the justices.

Rebuttals averaged 134.3 seconds, which amounted to nearly half of the amount of time many justices took for each of their turns.

These measurements do not suggest that Roberts was ideologically motivated in the way he allocated time among the justices, as he allotted large amounts of time to both more liberal justices Sotomayor and Kagan and more conservative justices Alito and Neil Gorsuch.

Questions and answers: justices’ decisions

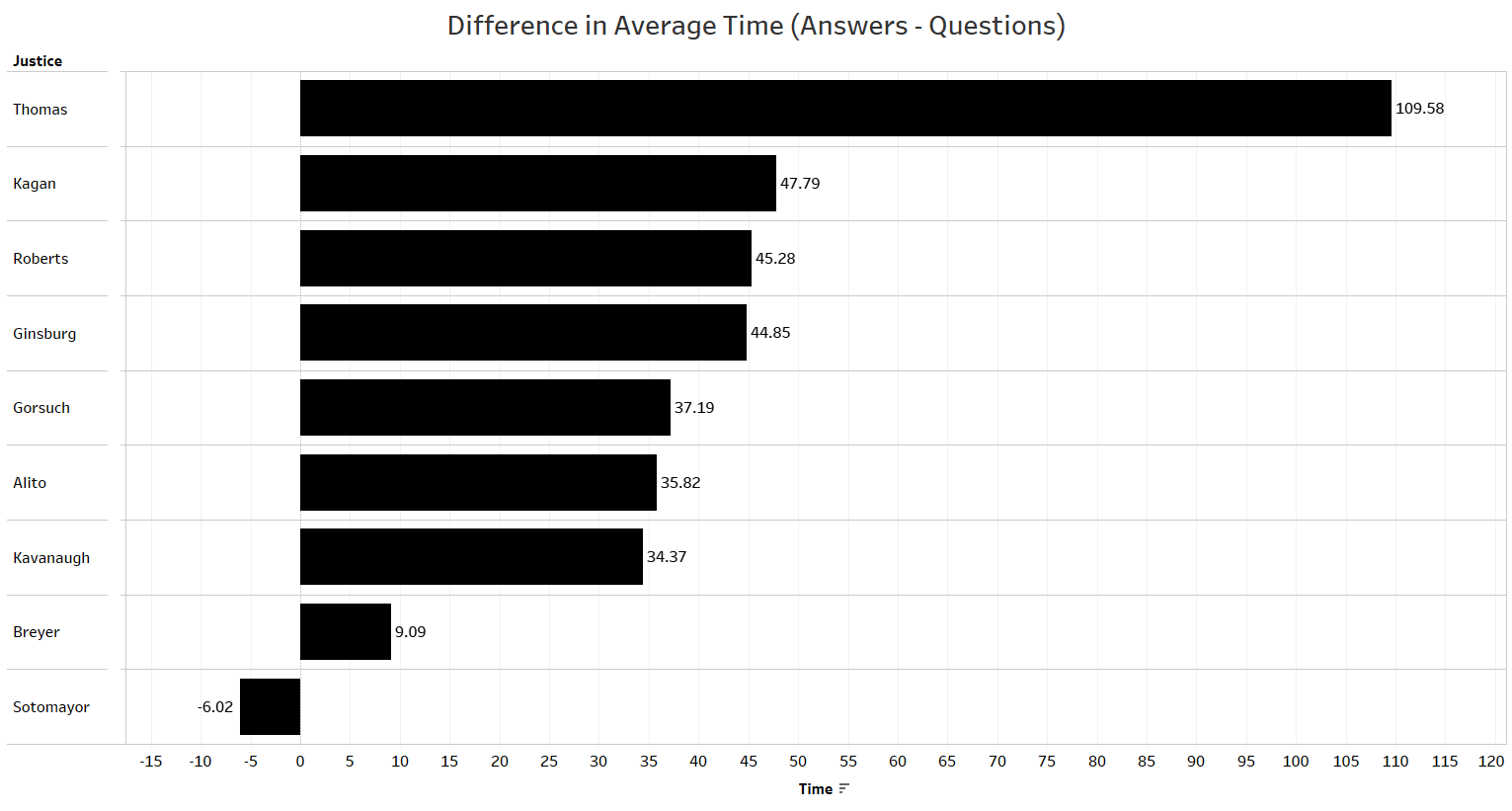

In a similar manner, we measured how the justices balanced time between asking questions and listening to answers during their argument turns. The graph shows the average differences between time left for answers and time spent asking questions by justice, ordered by those who left the most time for answers to the least.

Thomas left the most time for answers by far. His difference was 109.6 seconds in favor of answers. The remaining justices showed much more moderate differences in time between questions and answers, generally leaving between 30 and 50 seconds more for advocates to answer.

Six of the justices’ time differences between answers and questions fell into this 30 to 50 second range. With Thomas on the shorter end for questions, two justices spent much more time on questions. Justice Stephen Breyer, who is known for spending significant time on oration during oral argument, only averaged 9.1 more seconds left for answers. Sotomayor was the only justice to average more time on questions than answers, spending an average of six seconds more on questions.

Analysis

Large changes were afoot in the new-format oral arguments. This was something unexpected and for which no one was truly prepared. Given the way this argument format was in some ways forced on the court, the justices took the format changes in stride. From Thomas’ involvement to Roberts’ new role as timekeeper, each justice had a part in making these arguments work. Some differences in the justices’ behavior were notable as well. Alito took more time than other justices and Roberts took relatively little time. Thomas spoke more than many expected and spent the most time listening to advocates’ responses. Sotomayor, on the other hand, spent the bulk of her time asking questions and spent the least average time of the justices listening to the advocates’ responses.

There is no guarantee that any of the changes to this new format will be retained in future arguments. Some of this will depend on whether and to what extent the current pandemic lasts in into the OT 2020 argument season. Other decisions will relate to the justices’ level of comfort with changes to the old format, such as allowing live-streaming of arguments to continue. All in all, this experiment with the new format appeared successful in providing the justices with opportunities to ask questions and listen to answers without interruption from other justices.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS