“Supreme Advocacy”: supreme on style, a bit light on substance

We haven’t had a film review on SCOTUSblog for quite some time now. Given that, we figured Bloomberg Law’s “Supreme Advocacy: What It Takes to Argue at the Supreme Court,” was the perfect candidate. The 40-minute documentary, directed by Andrew Satter, follows Supreme Court litigator Roman Martinez, a Latham & Watkins partner who has argued 16 cases in front of the justices.

Specifically, the film follows Martinez as he prepares for and argues the case of A.J.T. v. Osseo Area Schools, which the court heard back in April. In that case, Martinez led an appellate team on behalf of Ava Tharpe, a teenage girl with severe epilepsy whose parents challenged the scope of her educational accommodations under federal disability discrimination laws.

Like some other Supreme Court documentaries (a la “RBG”) the film is laudatory of its star. But it principally highlights the advocacy process. In the words of film director Andrew Satter: “I think a lot of documentaries about the Supreme Court usually focus on an issue or a person. We really wanted to tell a story about the process, about how this works.”

The film opens with a black and white b-roll of a gavel being struck. Some seconds in, we switch to demonstrators outside the court with signs from “protect trans youth” to “sex change is a fantasy” and “bans off our bodies” to “abortion is murder.” “You can hardly think of a subject that matters to you as an individual that will never come before the supreme court,” says reporter Nina Totenberg.

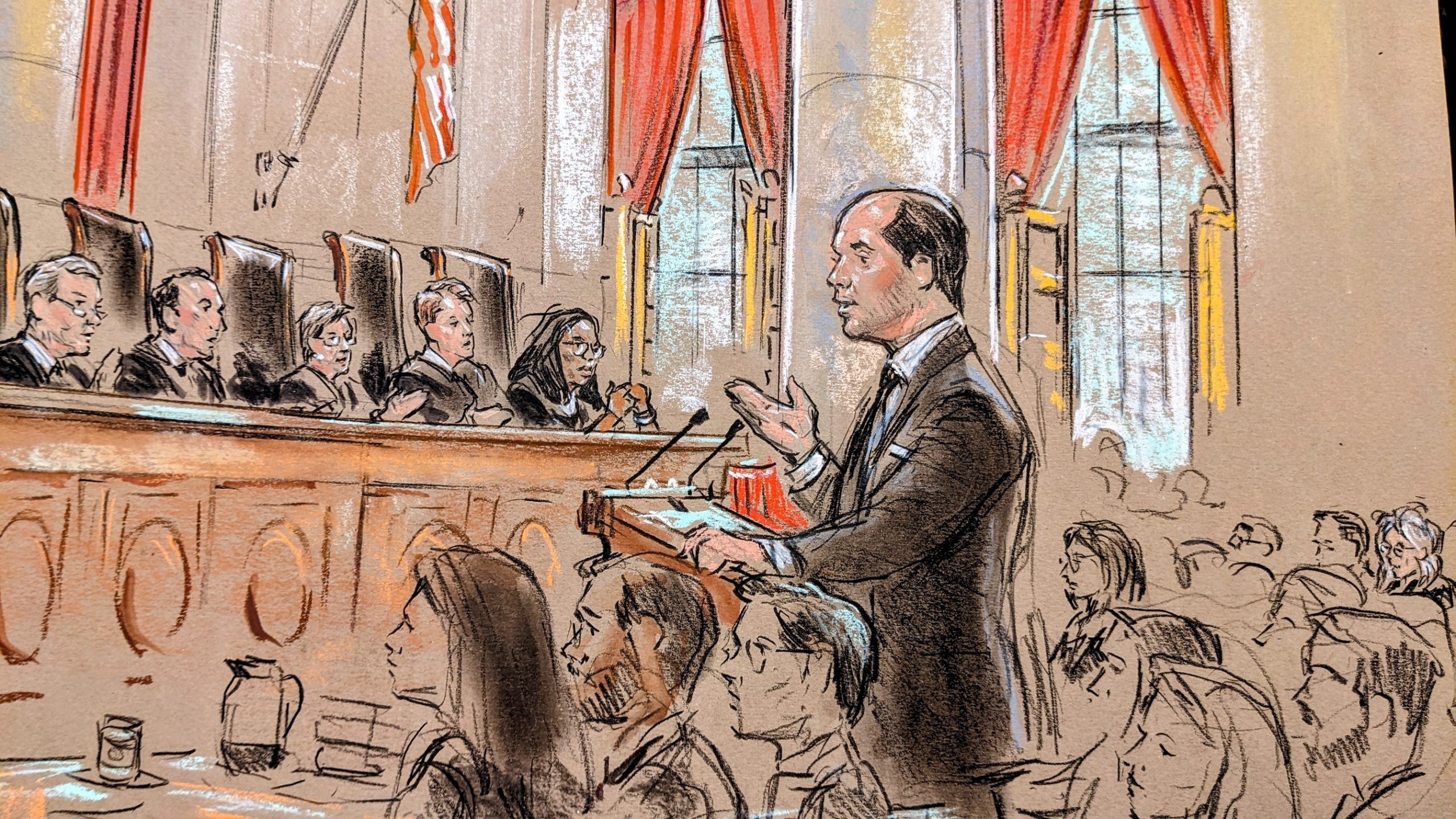

The documentary then pivots to Martinez himself, an extremely likable and down-to-earth litigator with the “pedigree you’d expect from an elite lawyer.” We learn about his Yale Law School education, his clerkship for Chief Justice John Roberts (complete with a framed photo and a warm inscription from Roberts), and Martinez’s time in the U.S. solicitor general’s office. Disappointingly, the film glosses over some of the most interesting aspects of Martinez’s background, like his role serving as an advisor on the Iraqi constitution or the substance of the 14 Supreme Court arguments before A.J.T. A sketch from Martinez’s highest-profile case, Relentless v. Department of Commerce (in which the Supreme Court overruled a longstanding doctrine on deference to administrative agencies) appears briefly, alongside a quote from Martinez praising the result as “a win for individual liberty and the Constitution.” Yet the documentary doesn’t delve into how such experiences informed his strategy in A.J.T.

A.J.T. itself is introduced through a Star Tribune headline about Ava’s family challenging the Osseo school district after their 2015 move from Kentucky to Minnesota, where the district refused to adopt her individualized education program and slashed her accommodations. Home videos of Ava’s seizures and her parents’ testimony – Gina and Aaron Tharpe describe how she lost her ability to communicate – also bring home the case’s personal stakes.

Bloomberg Law reporter Kimberly Robinson notes that many of the cases that make their way to the Supreme Court do so because the federal courts of appeals have reached different conclusions about the same legal issue. In A.J.T., however, the lower courts agreed on the damages for intentional discrimination but disagreed on what families like Ava’s must prove to show intent.

This is where the film’s emphasis on process shines. A clean timeline graphic traces the case from the family’s petition for review (filed after the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit ruled against Ava) to the grant of this petition, briefing before the court, and oral argument. We see Martinez’s team dividing research, editing drafts 20-30 times, and navigating amicus (“friend of the court”) briefs – including a supportive one from the U.S. government.

But, while I appreciated all the footage of Martinez working late (often with a sparkling water can in frame, as Sarah Isgur noted on a recent AO episode), the documentary doesn’t do a much deeper legal dive. We don’t really get any sense of how things played out in the lower courts or the nuances of the legal standard actually in play – the intent requirement at issue gets a passing nod but no real discussion. Rather, we get basics like the three branches of government, and other Schoolhouse Rock-like explanations that will already be familiar for anyone with a passing interest in civics.

So back to Martinez, where the film is at its best. We learn about his Cuban heritage (his father fled the revolution, his uncle was a Miami prosecutor), his family life in the D.C. suburb of Chevy Chase – complete with an “Honest Lawyer” pillow – and how he met his wife when she was a summer associate at another firm. A cute scene shows him bringing his daughter to the office, and we get a sense of Martinez’s pre-argument rituals (no all-nighters, unlike law school). The film also touches on his evolution as an advocate, and Martinez reflects on getting comfortable with the justices. (One thing missed: the film briefly shows a photo of Justice Brett Kavanaugh with Martinez’s children, but the fact that Martinez clerked for this justice when Kavanaugh was a judge is pretty much left out.)

After the argument, the documentary captures Martinez’s cautious optimism and the wait for decision day, showing him refreshing the Supreme Court website just like the rest of us. This ultimately resulted in a 9-0 win – and it’s delightful to watch Martinez announce that they won on a call with his team and the Tharpes. But it’s all a bit too simplistic: from early on, Martinez is fervently portrayed as the good guy, with everything reduced to a simple “hero’s journey” in which all the pieces align and the law’s actual nuances are left unexplored.

And then, of course, is the oral argument itself. The film sets the scene of the courtroom fairly well (for example, noting such things as the 94-inch diagonal distance between the advocate and the justices). There are also a few clips that capture some key moments, including an accusation by Lisa Blatt, who represented the school district, that Martinez and the government had lied in asserting that she had changed her position – which Martinez later states they have “moved past.” But, again, the film doesn’t clarify many of the issues actually raised by the justices, or delve into what these have to do with the arguments being made. Things are kept surface level, which will be frustrating to anyone (not just SCOTUS aficionados) looking to understand what, exactly, is going on here.

In the end, “Supreme Advocacy” excels on style, and viewers will appreciate its behind-the-scenes access and Martinez’s extremely likeable nature. It also weaves in some humor (a toilet flush heard while Martinez was arguing over the telephone during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as former U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar’s penchant for eating several bananas before an argument) amid the serious issues at stake. But it’s rather subpar on substance, treating the audience like they can’t handle the “why” behind the wins.

Posted in Film Review

Cases: A.J.T. v. Osseo Area Schools, Independent School District No. 279