Supreme Court clerks and networks of power

Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

Sarah Sloan, a Columbia Law School graduate who clerked for Justices John Paul Stevens and Elena Kagan, told her law school’s alumni magazine that she never thought she’d wind up at the Supreme Court until she was encouraged by professors and federal judges who knew the path well. Reid Coleman, who graduated from the University of Texas School of Law, had an early White House stint, two appellate clerkships with prominent judges (on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th and District of Columbia Circuits), faculty-backed clinics, and then spent his capstone year with Justice Clarence Thomas – before landing at Kirkland & Ellis.

Both former clerks’ stories serve as a case study in how modern pipelines run: mentors and repeat-player judges smooth the way, district and appellate feeder judges (judges who commonly send clerks to the court) credential the résumé, and an elite firm scoops the clerk up. Texas Law’s climb in federal placements and, with Coleman, its 40th Supreme Court clerk, show the center of gravity widening beyond the usual Ivy duopoly (that is, Yale and Harvard). But the architecture remains the same: tight networks, long apprenticeships, and a hiring market that channels new court alumni into a handful of powerful institutions poised to shape litigation for years to come.

The clerkship universe

One former Roberts clerk described his clerkship simply: “It’s not just a credential—it’s an entire professional universe.” That universe is why firms now pay signing bonuses of up to $450,000 to attract clerks fresh out of One First Street, a practice so entrenched that it has reshaped lateral hiring at the country’s most profitable law firms.

The exclusivity of the system has long been recognized by scholars and commentators, though not always in a positive light. One Columbia Law Review article, for example, noted how Supreme Court clerkships concentrate opportunity in a handful of schools and chambers. The result is a cycle: the same institutions that dominate clerk hiring replicate their influence generation after generation.

The clerkship universe has not remained stagnant, however. From Justice Clarence Thomas’ first term in 1991 to the newer chambers of Justices Amy Coney Barrett and Ketanji Brown Jackson, the clerkship market has retained its familiar concentration in a handful of schools and feeder judges. But this continuity is paired with real shifts – longer timelines to the court, new district-level pipelines, and widening gaps in cross-party hiring. If anything, however, this reveals how the clerkship system is steadily hardening into even more defined networks of power.

Time to the court

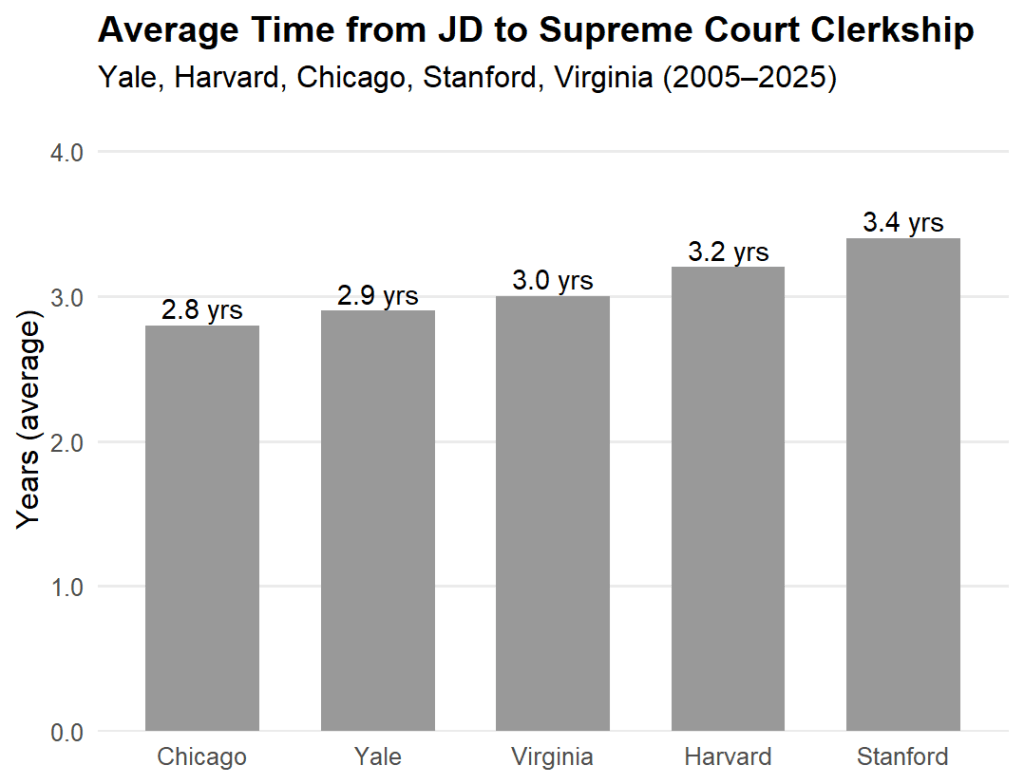

One of the more notable shifts is how long it now takes between graduating from law school and a Supreme Court clerkship. This timeline has lengthened considerably. In the mid-2000s, new Supreme Court clerks typically arrived about 2.5 years after law school; 20 years later, the average is closer to 3.8 years. This pattern reflects two shifts: candidates increasingly add a second clerkship or a year in the solicitor general’s office or at the DOJ before applying for a Supreme Court clerkship, and the feeder system rewards deeper résumés.

Clerks are not assistants so much as extensions of the chambers’ work – screening petitions, drafting opinions, and debating strategy – so it’s unsurprising that justices and feeders alike prize additional seasoning.

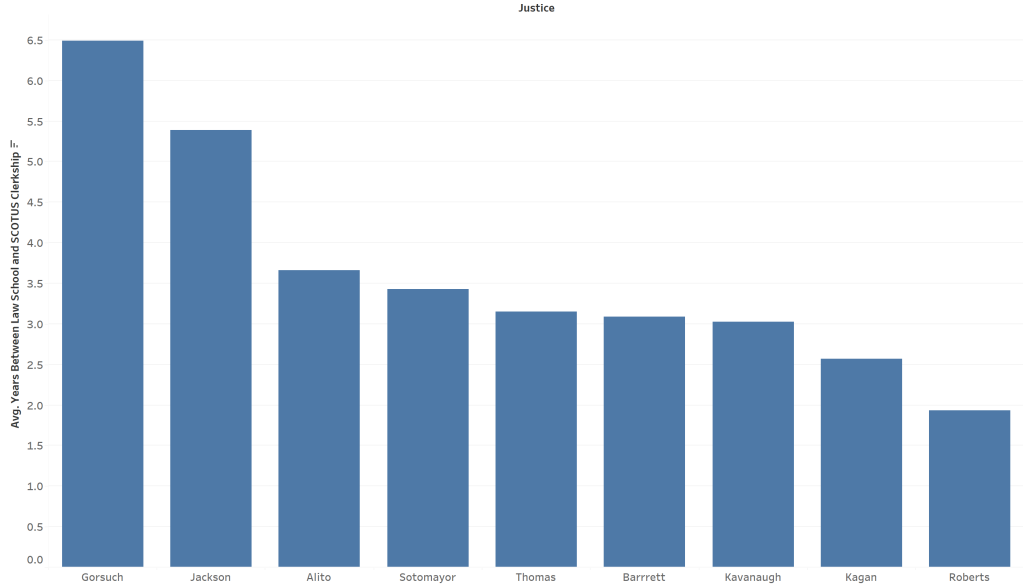

The differences by justice are also striking. Thomas and Justice Samuel Alito most often hire on the traditional cadence – one year with a repeat appellate feeder judge, then straight to the court – yielding compact timelines. In Chief Justice John Roberts’ chambers, there are two lanes: a fast track for those who clerked for certain judges on the D.C. Circuit and a longer path that includes a year with district court feeder judges in D.C. or the Southern District of New York before the court of appeals. Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s hiring mirrors that mix. On the left, Kagan and Justice Sonia Sotomayor show wider spreads; hires worked for the DOJ or solicitor general’s office between clerkships. Justice Neil Gorsuch often has the longest conservative-side tail, reflecting two prominent lower-court stops prior to the Supreme Court.

Gatekeeping by professors, feeder judges, and former Supreme Court clerks – often the same people writing recommendations and informally screening applicants – adds steps and time, and it tends to channel candidates within existing ideological and institutional networks. The result is credential stacking: two lower-court clerkships are common; short stints in the solicitor general’s office or DOJ appellate units signal readiness; and elite fellowships serve as holding patterns while recommendations are lined up.

As evidenced above, among the top law schools, patterns diverge. Yale is the steadiest: most clerks arrive in two to three years through a small circle of dominant feeders. Chicago is just as fast and tight, reflecting deep ties to conservative appellate judges who hire and recommend on a predictable cadence. Harvard hits a similar mean but with a wider spread; graduates fan across circuits and into government roles, producing both fast tracks and “seasoned” four- to five-year paths. Stanford skews a bit longer, often adding an extra lower-court year or appellate-shop stint en route to D.C. from the West Coast. Virginia looks closer to Chicago: durable relationships with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th and 6th Circuits keep many UVA clerks in the two- to three-year band.

Cross-party hiring

The easiest way to see how polarized the pipeline has become is to look at who hires clerks who previously worked for judges of the opposite party; the pattern today is concentrated in a few chambers and nearly absent in others. Roberts, Kagan, and Sotomayor still reach across the aisle with some regularity – Roberts at 25% of his clerks with known prior-judge affiliations, Kagan at 26%, and Sotomayor at 21%. By contrast, the conservative supermajority’s core shows very little cross-party movement: Kavanaugh is at 9%, Gorsuch is at 3%, and Alito and Thomas are at 0%. Barrett and Jackson also show no cross-party clerks to date, though their totals are small.

The mechanics behind these numbers are visible in the rest of the pipeline. First, feeder networks are ideologically sorted to a degree that wasn’t as pronounced two decades ago. Repeat-player chambers on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C., 6th, and 11th Circuits –and, more recently, district courts in Washington, D.C., and Manhattan – tend to recruit and recommend within like-minded circles. Second, the value of former-clerk and repeat-feeder endorsements compounds over time, amplifying the same networks. And because the overall time to the court has lengthened, candidates now spend more time inside a single ecosystem before reaching the Supreme Court – extra years that, in practice, seem to reduce rather than increase cross-party movement.

Where they went next

Former Supreme Court clerks don’t just go far; they go fast. A detailed CNN reconstruction of the 2002–03 class shows how quickly clerkship cohorts move to the center of high-stakes litigation and government power. Just some examples: Adam Mortara became a lead architect of the lawsuit that ended affirmative action in college admissions; Jonathan Mitchell engineered Texas’ SB 8 abortion law; David Stras now sits on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit; Robert Hur served as special counsel in the Biden documents investigation; Toby Heytens is on the 4th Circuit; and Jesse Furman is a Southern District of New York judge.

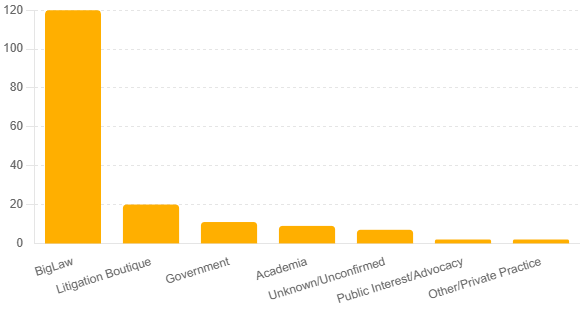

Looking at clerks from the 2019-20 to 2023-24 terms, Big Law accounts for 70% of placements, with litigation boutiques at 11%, government at 6%, and academia at 5%. A handful of firms dominate first jobs. Jones Day leads with 19% of placements, followed by Gibson Dunn and Kirkland & Ellis. Roughly one in five clerks starts at a single firm, and nearly half land at just three firms.

The immediate market signal is a blunt one: law firms pay signing bonuses approaching $450,000 to recruit Supreme Court alumni, a figure that now significantly exceeds a justice’s annual salary. Empirical work underscores the downstream effect: cases argued or filed by former Supreme Court clerks receive a measurably different reception at the court, and those alumni are overrepresented among federal judges and top government lawyers. And because the modern path increasingly runs through ideologically aligned feeder judges, the careers that follow often carry that alignment into the federal judiciary and the executive branch.

What it means

The numbers tell a simple story with outsized consequences: clerkships are pipelines. The path is longer than it was two decades ago and increasingly routed through a narrow set of schools, feeder judges, and ideologically sorted networks. Cross-party hiring is now the exception, largely concentrated in three chambers, while most others pull almost exclusively from their own side. On the back end, a small cluster of firms absorb the bulk of new alumni – sweetened by six-figure bonuses – while a thinner stream moves into government, academia, and the bench, carrying those same networks into the institutions that argue, interpret, and enforce the law.

What comes next follows from the machinery already in motion. District-court pipelines and rising feeder judges could harden into permanent lanes; new chambers may either replicate today’s polarization or build bridges that have mostly disappeared. However the lanes settle, the stakes are structural: who gets hired today will shape which cases get filed, which arguments are heard, and which rules govern a decade from now.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS, Recurring Columns