Empirical SCOTUS: The big business court

on Aug 8, 2018 at 4:51 pm

The current Supreme Court is friendly toward big business. How friendly? If the court’s trajectory continues, perhaps as friendly as any court dating back to the Lochner era, when laissez-faire policies permeated the court’s rulings. Prominent scholars, most notably Lee Epstein, William Landes and Richard Posner, have found empirical support for the proposition that the current court is more pro-business than previous iterations. (That study was recently updated through the 2015 term.) This post uses data from the 2015 through 2017 terms to add to this discussion. In particular it seeks to locate the trajectory of the court with the possible addition of Judge Brett Kavanaugh for the October 2018 term. Although the court’s right and left sides found themselves on opposite ends of business rulings during the October 2017 term, we might expect an even stronger pro-business court next term with the addition of another likely predictably pro-business justice in Kavanaugh.

The last three years

Not that Justice Anthony Kennedy tended to clash with conservative positions in business rulings. On the contrary, Kennedy authored many decisions that enhanced the power of businesses, including the court’s decision giving corporations First Amendment free speech protection in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. Still, for the 2015 through 2017 terms, Kennedy was less pro-business than several of his conservative counterparts.

This figure was created by coding all of the court’s orally argued cases from the October 2015 through 2017 terms as focused on a business interest or not and then narrowing the scope to cases that pitted a clear business interest against a contrary interest, thus excluding cases with dueling business interests. Sixty-six cases met the narrowed criteria that underlie the construction of the figure above.

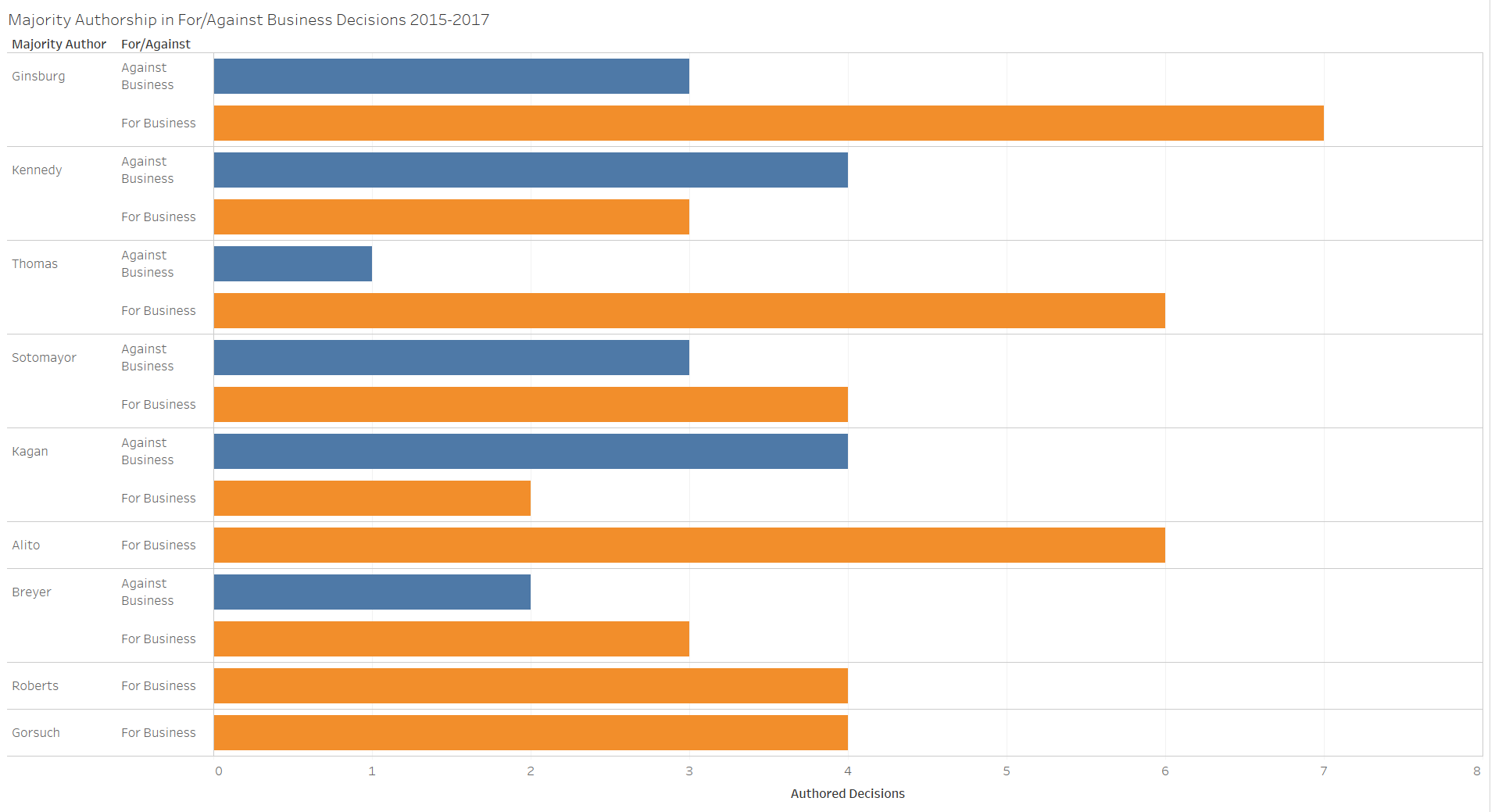

The next figure examining majority opinion authorship in pro/anti-business decisions corroborates this account of greater recent conservative support for business interests.

Three of the more conservative justices – Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch — only authored pro-business majority opinions during this period within this set of cases. Kennedy was the only conservative justice to write more anti- than pro-business opinions during this period.

An even bigger push for business

While the court continued its pro-business trajectory during the past three terms, it also increased its pro-business momentum over this period. This increase is evident based on the court’s fraction of pro-business rulings. The following figure looks at the number of cases the justices heard across the 2015 through 2017 terms that contained pro- and anti-business interests as well as the percentage of these decisions that were pro-business.

Although the court heard fewer business-related cases in the 2017 term, it heard fewer total cases last term as well, making the downshift in business cases more proportional to the court’s actual merits docket. With this curtailed caseload, the court ruled 81.25 percent of time in favor of pro-business interests. Even in the few cases in which the court ruled against business interests, the downstream effects on business interests may not necessarily be negative in the aggregate. One example of this is the court’s decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair. [Disclosure: Goldstein & Russell, P.C., whose attorneys contribute to this blog in various capacities, was among the counsel to the petitioner in this case.] Although the court’s immediate holding allowed states to tax out-of-state businesses, this decision may end up enhancing competition by leveling the advantage out-of-state businesses had over in-state businesses.

Major interests

Because the stakes in these cases are quite large, the parties marshal support from some of the top Supreme Court advocates. The list of repeat attorneys in this set of cases from 2015 through 2017 is a veritable who’s who of the Supreme Court bar.

Many of the most notable appellate attorneys now in practice argued several of these cases, with Paul Clement in the lead, followed by fellow veteran Supreme Court attorneys Carter Phillips, David Frederick and Seth Waxman. Although several other big-firm attorneys top this list, the list also includes a handful of attorneys from smaller appellate boutiques, including Peter Stris and Daniel Geyser from the Los Angeles based firm Stris & Maher (Geyser has since started his own boutique, Geyser PC) and Thomas Goldstein, from the D.C.-area firm Goldstein & Russell (who is the publisher of SCOTUSblog).

Amicus support for positions in these cases is another indication that these outcomes matter to a variety of interests. Many of these cases had over 10 merits amicus briefs, while several had 20 or more. The cases in this set with the top number of cumulative merits amicus briefs supporting the petitioners’ or respondents’ positions are displayed below.

The two cases with the most merits amicus briefs were Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association and Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees , which both involved mandatory union dues. Several patent-related cases, Oil States Energy Services v. Greene’s Energy Group and Impressions Products v. Lexmark International, also made the top of the list, along with two other cases from this past term — Wayfair and Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis. These cases already make up a large portion of the court’s docket, so we may expect to see an even greater influx of similarly minded petitions as the court moves policy in an even more favorable direction for big businesses. [Disclosure: Goldstein & Russell, P.C., whose attorneys contribute to this blog in various capacities, was among the counsel on amicus briefs in support of the respondents in Janus and in support of the petitioner in Oil States.]

What to expect

If Kavanaugh is confirmed by the beginning of the 2018 term, we can expect the court to be even further inclined towards ruling in favor of business interests. The first indication of this is from the first figure in this post, which shows that Kennedy was on the lower end of support for business interests over the last three terms for the conservative justices on the court.

Furthermore, although the court sided with pro-business interests more frequently last term than it has in previous terms, many of these were decided by a narrow margin. The following figure shows the difference in majority and minority votes in this set of decisions for the past three terms (the row labeled “1” is for cases decided by a single vote).

The justices decided eight business-related cases last term by one vote. That was compared to one such decision in both the 2016 and 2015 terms. Although not all of the decisions were based on close votes in the past several terms, we may expect more hotly contested cases on the horizon, especially if the court’s liberal and conservative justices continue to rule in divergent directions.

With this increased polarity, Kavanaugh will in all likelihood provide greater support for pro-business interests. What support is there for this proposition? The best signs are from his written opinions while on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. His opinions in the following cases are not only examples of his positions, but cumulatively show a propensity to rule in big businesses’ favor. These cases constitute the set of pure business cases as coded for a previous post.

In Wu v. Strombler, Kavanaugh wrote an opinion that ruled in favor of Carlyle Capital, which was accused of making material misstatements and omissions to investors about the sale of securities.

Kavanaugh wrote an opinion in favor of ExxonMobil in Metroil v. ExxonMobil, in which Exxon was accused of violating state and federal laws by selling a station leased and operated by Metroil to Anacostia, a gasoline distributor.

Kavanaugh wrote the majority opinion in Stilwell v. Office of Thrift Supervision, in which the D.C. Circuit upheld a regulation that allowed subsidiaries of mutual holding companies to limit minority shareholders to 10 percent of the subsidiary’s minority stock in order to prevent minority holders from taking advantage of voting rules regarding stock benefit plans.

In Pirelli Armstrong Trust v. Raines, Kavanaugh wrote for the majority holding in favor of Fannie Mae in a case dealing with a series of accounting failures reported in corporate earning restatements. Kavanaugh’s opinion upheld the district court’s ruling against allowing shareholder derivative suits filed against Fannie Mae’s directors.

In Doe v. ExxonMobil, Kavanaugh dissented in favor of Exxon in a case in which Exxon was sued under the Alien Tort Statute for aiding and abetting Indonesian officials’ abusive behavior towards Indonesian citizens.

Although Kavanaugh was consistently on the pro-big-business side of these decisions, not all these cases divided the panels ideologically. Several judges appointed by Democrats sided with Kavanaugh in some of the decisions listed above, including Judges Merrick Garland and Harry Edwards in Metroil. This is likely a similar orientation to what Kavanaugh will find on the Supreme Court if he is confirmed — the liberal and conservative justices often rule in the same direction in these cases, even though that pattern was inconsistent last term.

Although the Supreme Court still has a little less than half of its 2018 docket to fill, many cases on the horizon will juxtapose pro and anti-business interests. Attorneys in several of these cases are listed in the attorney figure above, further amplifying this trend of repeat attorneys in this set of cases. These cases include:

- Weyerhaeuser Company v. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, which involves a challenge by a timber company to an endangered-species designation.

- New Prime Inc. v. Oliveira, which deals with an exemption from the Federal Arbitration Act.

- Air and Liquid Systems Corp. v. Devries, which is a products liability case.

- Virginia Uranium v. Warren, which looks at federal versus state regulations on uranium mining.

- BNSF Railway Company v. Loos, which involves the applicability of taxes on lost-time payments.

- Fourth Estate Public Benefit Corp. v. Wall-Street.com, which examines when the registration of a copyright claim is complete.

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. v. Albrecht, which deals with a failure to warn claim.

- Apple v. Pepper, which focuses on consumers’ right to sue a deliverer of goods for antitrust damages.

- Lamps Plus v. Varela, which looks at whether the Federal Arbitration Act precludes a state law interpretation of an arbitration agreement.

- Henry Schein Inc. v. Archer and White Sales, another Arbitration Act case, in which the court will consider when a court can decline to enforce an arbitration agreement.

- Helsinn Healthcare S.A. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, in which the court will look at questions surrounding when a sold item can be properly patented.

- Lorenzo v. Securities and Exchange Commission, which examines whether a misstatement claim can be repackaged into a fraudulent-scheme claim.

From the previous figure of repeat player attorneys, the following attorneys are already counsel of record in the list of cases above (the numbers in parentheses indicate the number of these cases in which these attorneys are already listed): David Frederick (3), Shay Dvoretzky (2), Kannon Shanmugam (2), Peter Stris, Carter Phillips and Andrew Pincus.

The convergence of the factors described above almost ensures that a large portion of the court’s docket will be filled with cases implicating businesses’ interests. If Kavanaugh is confirmed, we can expect the pro-business direction of the court’s rulings to continue and perhaps even to increase in momentum. With five solid conservative votes on the court, the conservative justices will have more control over the court’s docket, as they can predict their desired outcomes each time they congregate as a united front. If they do so they will have great leeway in case selection and in setting the court’s course, whether in favor of pro-business interests or otherwise.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.