Why the Supreme Court agrees to hear some cases and not others

Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

Please note that the views of outside contributors do not reflect the official opinions of SCOTUSblog or its staff.

Most people think the Supreme Court’s big moments happen at oral argument. They don’t. The decisive act for nearly every case is earlier and quieter: a secret vote on whether the court will even hear it. That gateway vote – granting or denying review, also known by the Latin term “certiorari,” often abbreviated as “cert” – happens behind closed doors, guided by both the rule that four justices must agree to grant cert and a long list of unwritten habits. Because the court rarely explains those habits, even seasoned lawyers talk about cert in the language of hunches, rather than certainties.

By analyzing a dataset of Supreme Court petitions from 2017-2024, I have been able to shed some light on this mysterious process, and determine what factors increase the odds that the court will grant your case.

The data

A quick word on definitions. Every cert petition is either “paid” (filed with the $300 filing fee, typically by litigants who are represented by an attorney) or “in forma pauperis,” or “IFP” – filed without the fee by indigent litigants, often prisoners representing themselves who are challenging their criminal convictions or prison conditions. IFP filings make up the bulk of incoming cert petitions, but they are granted far less often: Many raise frivolous issues or depend heavily on the facts, do not involve a clear disagreement among the lower courts on a legal question (one of the main criteria on which the court relies in deciding whether to grant review), or present questions that the court has repeatedly declined to revisit. Paid petitions, by contrast, are where the justices most frequently find suitable cases to serve as the basis for nationwide rulings.

The analysis that follows therefore focuses on the more than 12,300 paid petitions filed from 2017 through the end of 2024 and excludes the IFP filings. That focus does two things. First, it keeps the signal-to-noise ratio high by studying the petitions that realistically contend for limited merits slots. Second, it zeroes in on the strategies attorneys can actually use in attempting to have their petition granted – timing, counsel lineup, coalition building, and how to manage (or resist) relists (as explained below) – without mixing in a mass of cases that follow a very different path to almost-certain denial.

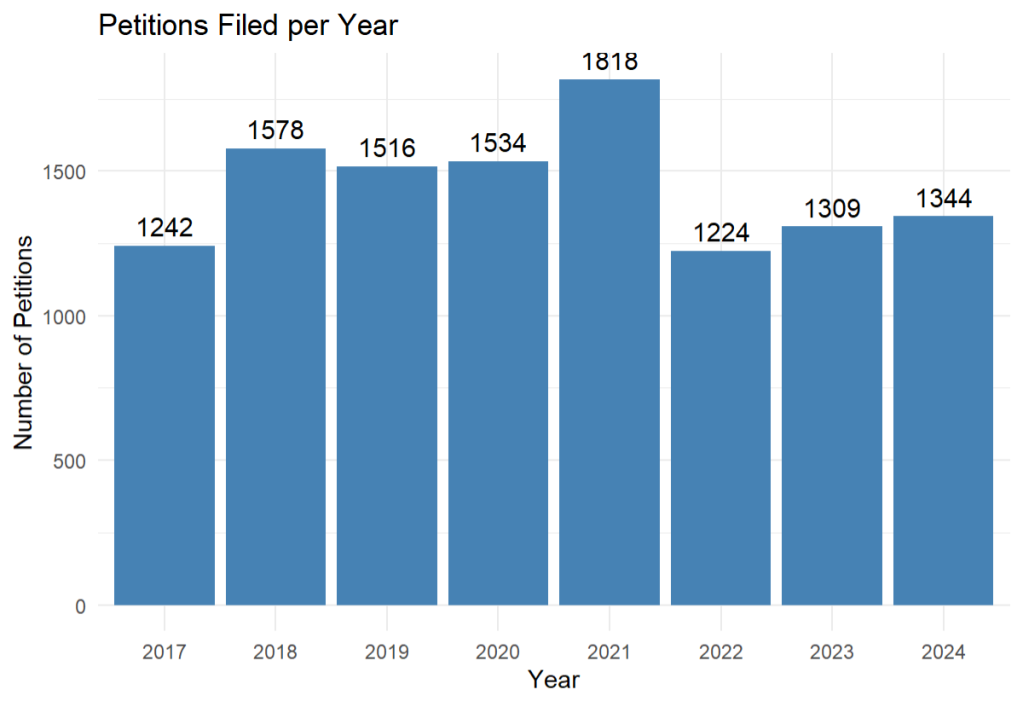

Petitions filed per year

Annual filing totals put the whole period in context. This bar chart is the backdrop for everything in the article:

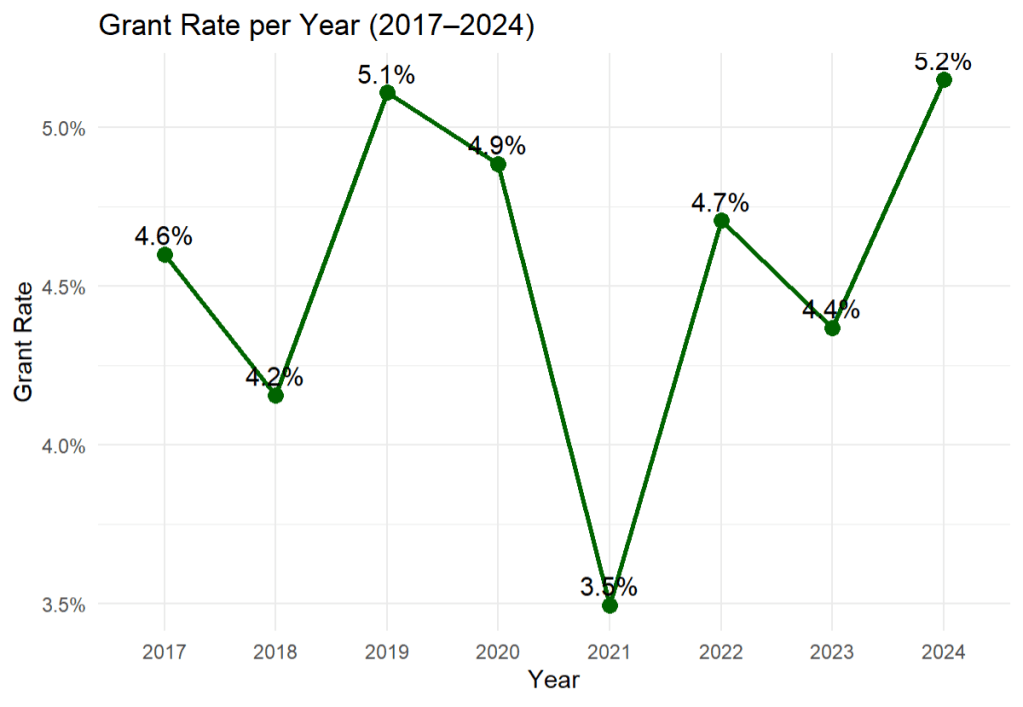

We can also see the change in yearly grant rates below (I removed GVRs or granted, vacated, and remanded petitions from this analysis to avoid conflating grant rates):

While the averages generally hover in the mid 4% range, there was a clear drop off in 2021 to 3.5%. Interestingly, the rates were over 5% in both 2019 and 2024.

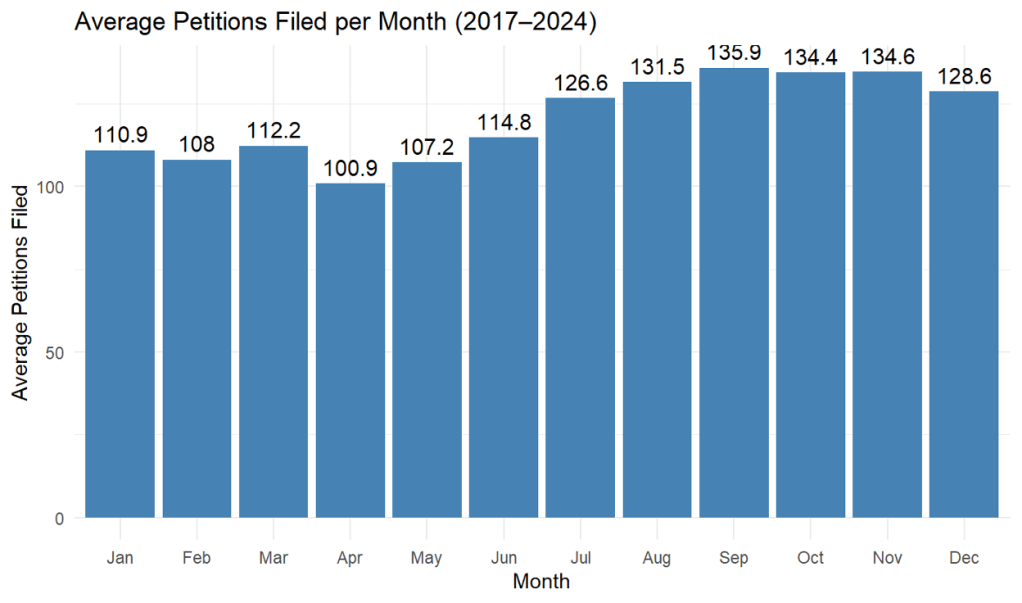

Average petitions filed per month

This figure shows how many petitions hit the docket each month, which in turn shapes how many cases the court must consider at its “long conference” – the justices’ private conference in late September, at which they consider all of the petitions for review that have accumulated over the summer – and how crowded the fall pipeline becomes. Use it to understand whether a given month’s grant rate is a function of appetite or crowding – or both.

Filings ramp up from late spring into fall, peaking between September and November. That peak aligns with the long conference’s heavy lift. It also helps explain why grant rates can be strong in early fall even as volume surges: The court must stock a merits calendar quickly. For litigants, this can cut both ways: You’re in a bigger crowd, but the court needs viable cases. A “crisp” petition with a clean division among the courts of appeals and without any complicating factors can benefit from that stocking pressure. In a crowded month, clarity wins.

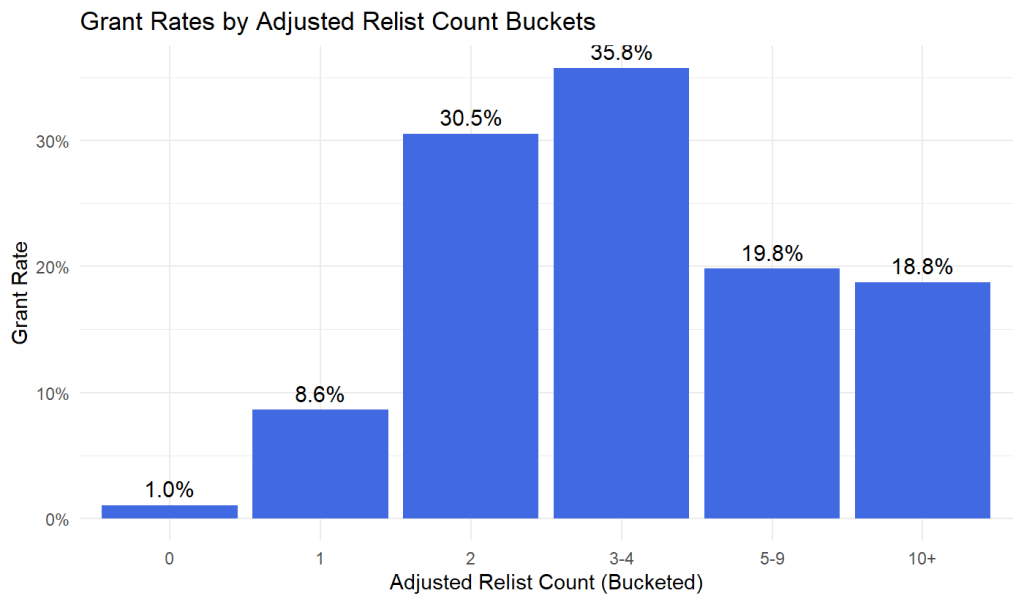

Grant rates by relist count buckets

Relisting is the court’s most visible, day-to-day tell during the cert stage. When the justices relist a petition, they decide to hear it at a later private conference rather than resolve it immediately. The outside world can see this because the justices do not act on the petition; instead, the electronic docket for the case will indicate that the case has been distributed for the next private conference. Practitioners often assume that the more relists a case has, the better the odds of it eventually being granted, but it is not that simple.

The figure below groups petitions by adjusted relist counts – normalizing it for “housekeeping” moves like rescheduling for administrative reasons – so we can see whether there’s a zone where a petition looks ready to grant, and whether multiple relists tend to mean something else (for example, some problem with the petition the justices are trying to fix, a push to narrow the question presented in the petition, or simply unresolved internal disagreement). Read the bars left to right as the court’s patience curve – how many relists typically signal momentum versus friction.

The climb from zero to a small number of relists is steep – the petition moves from almost no chance of being granted (at 1%) to decent odds of this. From there, the odds crest in the three to four relist “sweet spot” (at 35.85%) then decline for longer runs. That decline is the practical takeaway. If you’re the petitioner – that is, the litigant seeking Supreme Court review – and you’re past the fourth relist, you may assume the justices are wrestling with a defect in your petition. If you are the respondent – the party who won in the lower court – the same curve counsels patience: Past the sweet spot, the marginal value of another relist makes it less likely that your petition will be granted. Either way, the figure reframes a common myth: Relists are information, not a trophy count.

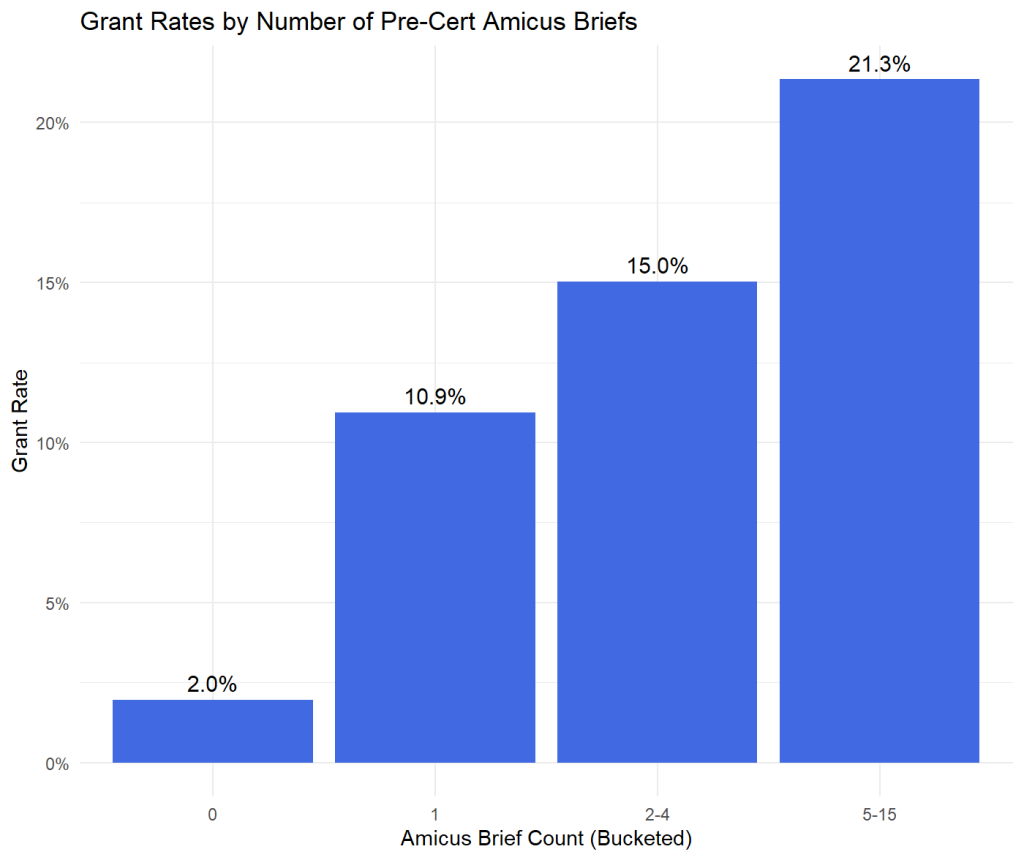

Grant rates by number of cert-stage amicus briefs

Cert-stage amici – briefs filed by “friends of the court,” almost always urging the court to grant review – are a classic way to signal that a case has national stakes, a division among the courts of appeals, or both. The question is whether additional briefs create momentum or merely document it. This bar chart buckets cases by amicus counts and tracks how the odds change with an additional amount of such briefs:

As the chart shows, each bucket of amicus briefs is associated with a higher grant rate, but the steps get smaller as the count climbs. Translation: Three or four well-targeted briefs are often better than a dozen repetitive ones. For petitioners, that means curating credible voices that cover different angles – doctrine, industry reliance, government impact – rather than collecting signatures.

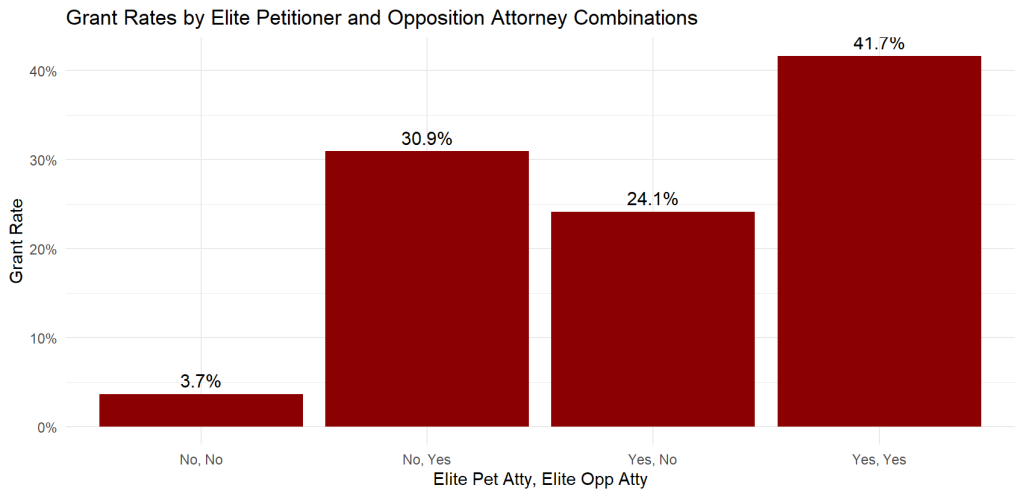

Grant rates by “specialist” attorneys

Supreme Court “specialists” (or “elite” petitioners) – attorneys who practice regularly before the Supreme Court – change the way petitions read. They trim the question(s) presented, anticipate obstacles, and, frankly, signal that the parties think the case is worthy of review.

This figure compares four matchups – cases without specialists, cases in which only the petitioner is represented by a specialist, cases in which only the respondent is represented by a specialist, and cases with specialists on both sides – so we can see how each configuration aligns with the odds of review. Specialists were designated based on Chambers & Partners Star individuals and band 1 attorneys. Think of it as a matrix for deciding whether, when, and how to bring in a specialist to file a Supreme Court petition.

As the chart shows, “no specialist” cases rarely get in – unsurprising, but useful as a baseline. More interesting: having only a specialist representing the respondent corresponds to a bigger lift than having only a specialist representing the petitioner, and having a specialist on both sides is the strongest of all. The asymmetry supports a practical rule of thumb: If it is plausible that the court could grant review and you’re opposing that review, hiring a specialist to represent you may signal a case’s importance in a way that actually persuades the court to grant the petition. Overall, the picture is clear: If you’re the petitioner, a specialist helps – but you’ll likely still need a case that has a division among the courts of appeals and is free from other complications to cash it in. And when both sides are represented by specialists, the court appears more comfortable granting: The case will likely be well-presented and opinions therefore easier to craft.

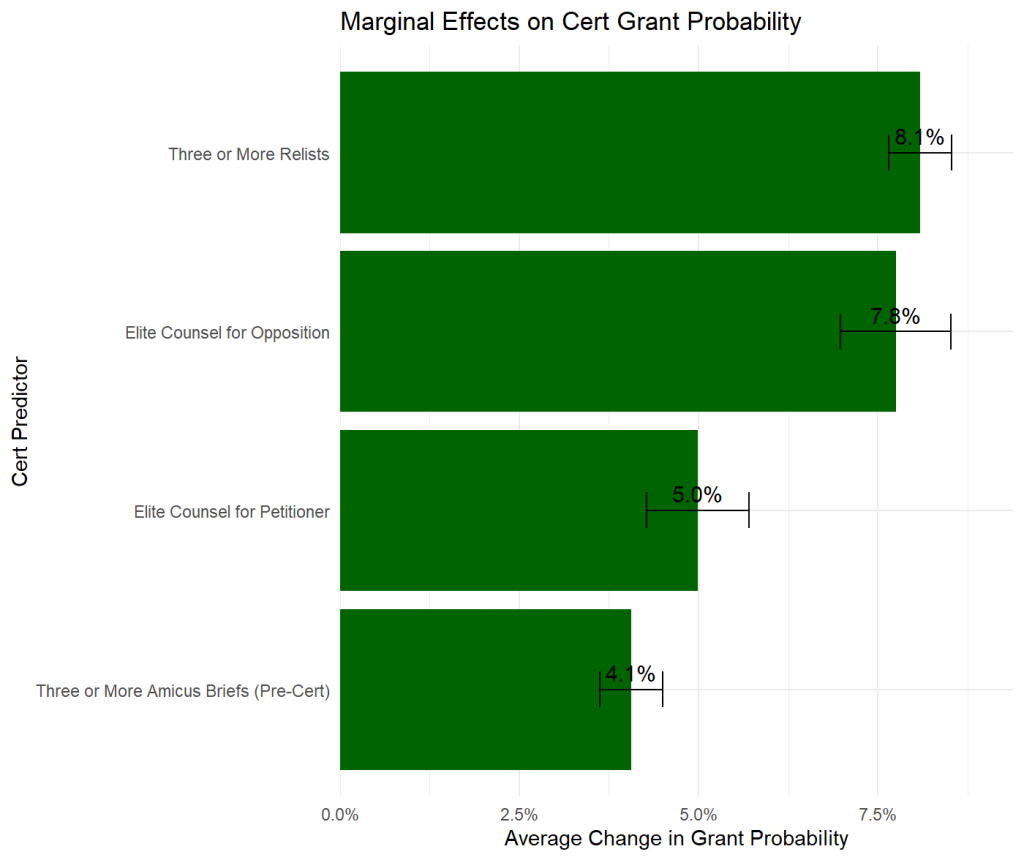

Marginal effects on cert grant probability

Different signals don’t operate in a vacuum. The horizontal bar chart below shows the average marginal effects from a unified model – specifically, how much each factor (the relist count, the use of Supreme Court specialists, and the filing of amicus briefs) changes the probability of a grant when the others are held constant. That “all-else-equal” perspective matters because many cert tells travel together (for example, strong cases attract amici and specialists and multiple relists).

Four levers consistently move the needle, in the following order: when the case is relisted three or more times, when the respondent is represented by a specialist, when the petitioner is represented by a specialist, and having three or more cert-stage amicus briefs.

Final thoughts

So where does this leave us?

For petitioners, the playbook is straightforward. Use targeted cert-stage amici to confirm the stakes of the case. If you add a specialist, make the presence of specialists in opposition part of the plan, not an afterthought; the court seems most comfortable granting when both sides have elite lawyers. Above all, fix legal and factual complications in the case early; if you need to narrow the issues in the case, do it yourself before the court does it for you – or before a run of relists turns into a slow “no.”

For respondents, the data justify having representation from a specialist. This is beneficial for crafting a strong argument and it can also lead to higher odds that the court will grant review.

None of this proves causation; the court will always keep some habits behind the curtain. But these patterns are stable enough to replace folklore with planning. Cert is rationing under secrecy, but it’s not random. Read the tells, budget for the levers that actually move the probability of review, and be willing to pivot when the relist curve turns against you. Strategy at the Supreme Court isn’t about confidence; it’s about calibration.

A longer-form version of this piece can be found at Legalytics.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS, Recurring Columns