The Supreme Court’s vanishing fall docket

Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

By the middle of January of this term, the Supreme Court had issued seven decisions in argued cases. For casual observers, this might seem unremarkable. But anyone tracking the court’s recent patterns knows that something unusual is happening: the 2025-26 term represents a striking departure from a recent trend that had seen early decisions nearly vanish from the court’s calendar.

An analysis of more than 1,700 argued cases decided between 2000 and the beginning of the 2025-26 term reveals a dramatic transformation in when the Supreme Court releases its opinions. The court that once regularly issued a fifth of its decisions before February has, in recent years, pushed an overwhelming majority of its work to the final weeks of June. This shift raises questions about the court’s internal processes, the complexity of its docket, and whether institutional changes have significantly altered the rhythm of Supreme Court decision-making.

The disappearing act: early-term decisions in decline

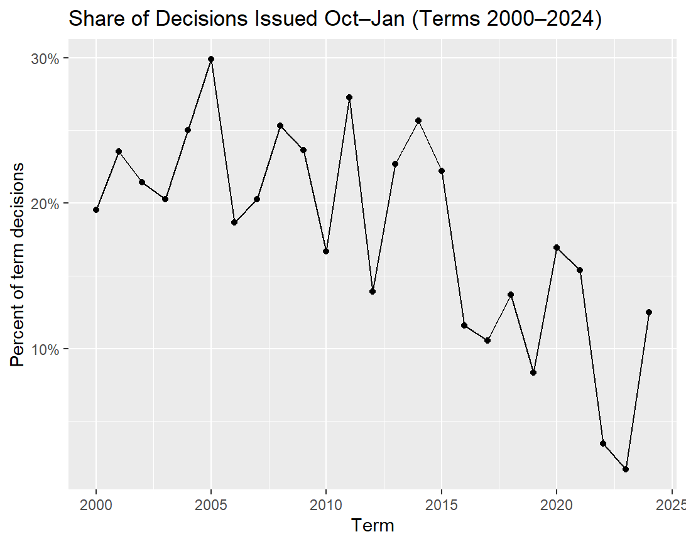

The numbers tell a stark story. From the 2000-01 term through the 2015-16 term, the court routinely issued between 15% and 30% of its decisions in the period between October and January. These early releases often involved straightforward cases with broad agreement among the justices, allowing the court to clear its docket and focus attention on more contentious matters scheduled for later in the term.

Then something changed. Beginning around 2016, the proportion of early-term decisions began to plummet. By the 2023-24 term, the court issued only two decisions between October and January – a modern anomaly. The 2024-25 term was only marginally different, producing just a single decision between October and January, representing less than 2% of that term’s output. For two consecutive terms, the court thus essentially abandoned its practice of issuing opinions in the fall months. In other words, the tradition of the “fall docket” – a recognizable feature of the court’s calendar for decades – effectively disappeared.

This year’s rebound to seven decisions by late January (12.5% of the term’s expected output) therefore stands in sharp contrast to the prior two terms. Whether it represents a course correction or merely a temporary deviation, however, remains to be seen.

The June crunch: when everything happens at once

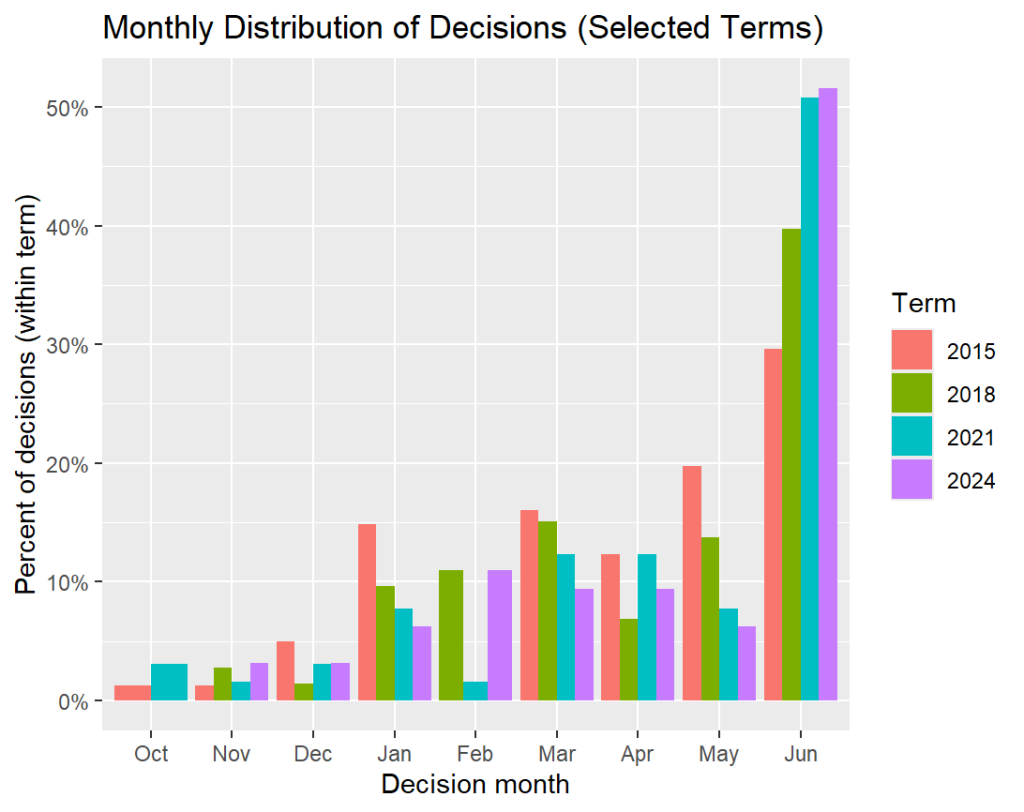

What is clear is that, as early-term decisions dwindled, the court’s output became increasingly concentrated at the opposite end of the calendar. June, traditionally the court’s busiest month, evolved into something approaching a decision-release marathon.

The numbers are, again, striking. Since 2000, June accounted for roughly 30-35% of the court’s annual decisions. In recent terms, that figure has exploded. During the 2023-24 term – the same term that produced only two decisions between October and January – a staggering 84.5% of all decisions came in the April-through-June window, with June alone accounting for 50% of the term’s output. The 2024-25 term showed a similar pattern, with 76% of decisions concentrated in the final three months.

This concentration has practical consequences. News coverage of the court becomes compressed into a few frantic weeks, with multiple high-profile decisions often released on the same day. The public’s attention, already fragmented, must somehow absorb and process complex constitutional questions in rapid succession.

The compression also affects how the court’s work is perceived. When contentious decisions cluster at the term’s end, it can create the impression – accurate or not – that the justices deliberately hold controversial cases until the last possible moment. (Whether this reflects strategic calculation, the natural complexity of divided cases, or simply the randomness of when opinions are ready for release remains a subject of some debate.)

A lengthening deliberation: time from argument to decision

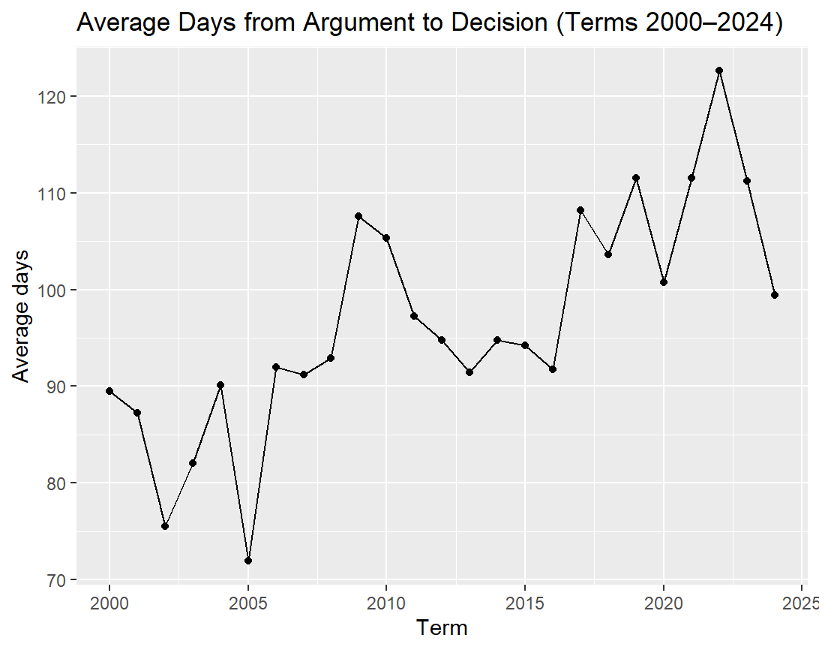

The court’s timing shift is not merely about when in the term it releases its decisions, but also about how long cases take from oral argument to an opinion. This next metric provides insight into the court’s internal deliberative process, and here too, the data reveals a significant change.

In the early 2000s, the average argued case took approximately 85-90 days from oral argument to decision. That figure has risen steadily. The 2022-23 term marked a recent peak, with cases averaging 122.6 days from argument to decision – nearly three weeks longer than the historical average. During this period, a case argued in early November would, on average, not see a decision until mid-March, and potentially much later.

Several explanations present themselves, none mutually exclusive.

First, the court’s docket may have grown more complex. Cases involving novel questions of statutory interpretation, constitutional first impression, or conflicts among multiple circuit courts require more extensive research, writing, and internal negotiation. Second, the court’s increasingly polarized composition may lead to longer negotiations over opinion language, particularly in cases in which a justice’s vote is uncertain. Third, the practice of separate opinions – concurrences and dissents – has proliferated in recent terms, and each of these opinions requires time to draft, circulate, and refine in response to the majority opinion. Fourth, the timing may have slowed down towards the end of the 2022-23 term and possibly into the 2023-24 term due to additional security protocols related to the leak of the Dobbs opinion. Finally, with the rise of the emergency application docket in around 2016, the justices have had the added burden of focusing on such applications over the summer and early into the term, which may lead to a delay in writing merits opinions until the end of each term.

Whatever the cause, the lengthening gap between the argument and decision contributes to the back-loading of the court’s term. Cases argued in October and November, which in earlier eras might have been decided by late January, now frequently extend into April or May, compressing the decision calendar even further.

The unanimity dividend: timing and consensus

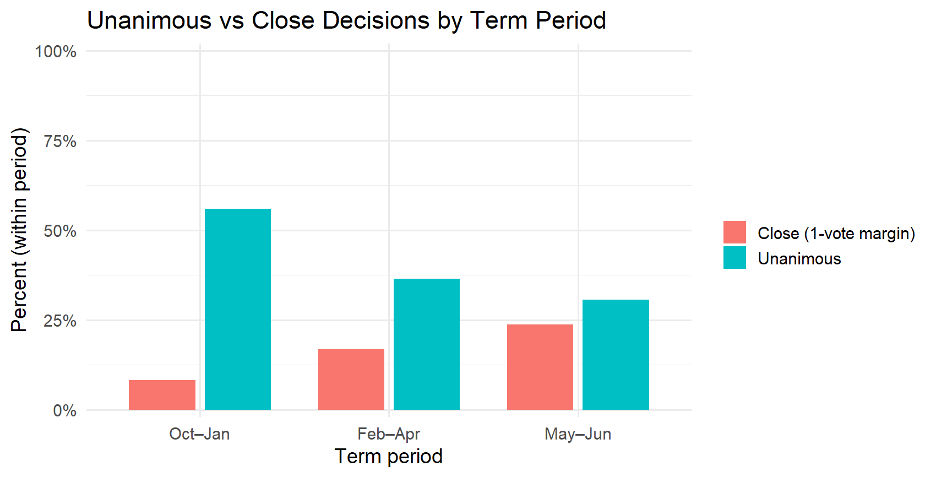

One of the most revealing patterns in the data concerns the relationship between case timing and vote division across the entire set of cases since the 2000-01 term. The numbers suggest a clear pattern (which should be quite familiar to court watchers): the court releases its less controversial decisions early and its most divisive cases later on. The figure below reports the share of decisions within each period that are unanimous (9–0) or narrowly divided by a single vote (5–4).

Consider the unanimity rates. Among the court’s most closely divided cases – particularly its 5–4 decisions – the likelihood of a narrow split increases steadily over the course of the term, peaking in May and June. Roughly half of decisions issued earlier in the term are unanimous, compared with closer to one-third of decisions late in the term, while 5–4 splits become roughly three times as common by May and June. This high rate of agreement early in the term may reflect the court’s apparent preference for clearing straightforward cases as soon as possible and pushing cases with more complicated vote splits to the latter part of each term.

The pattern becomes even more pronounced when examining the court’s closest cases. Among 5-4 and 6-3 decisions – the cases that commonly generate the most public attention and controversy – the overwhelming majority come in the final weeks of the term.

To be fair, this pattern suggests a rational workflow: the court resolves cases with broad agreement relatively quickly, allowing justices to focus their energy on cases requiring more extensive negotiation and compromise. But it may also reflect strategic considerations. Releasing unanimous or near-unanimous decisions early can help maintain the court’s public legitimacy, demonstrating that the justices can find common ground despite their philosophical differences. Saving divided cases for later minimizes the period during which the court faces criticism for those decisions while they are still deciding additional cases, as the term ends and they then quickly take their summer recess – potentially reducing the impact of any public response to their work in a given term.

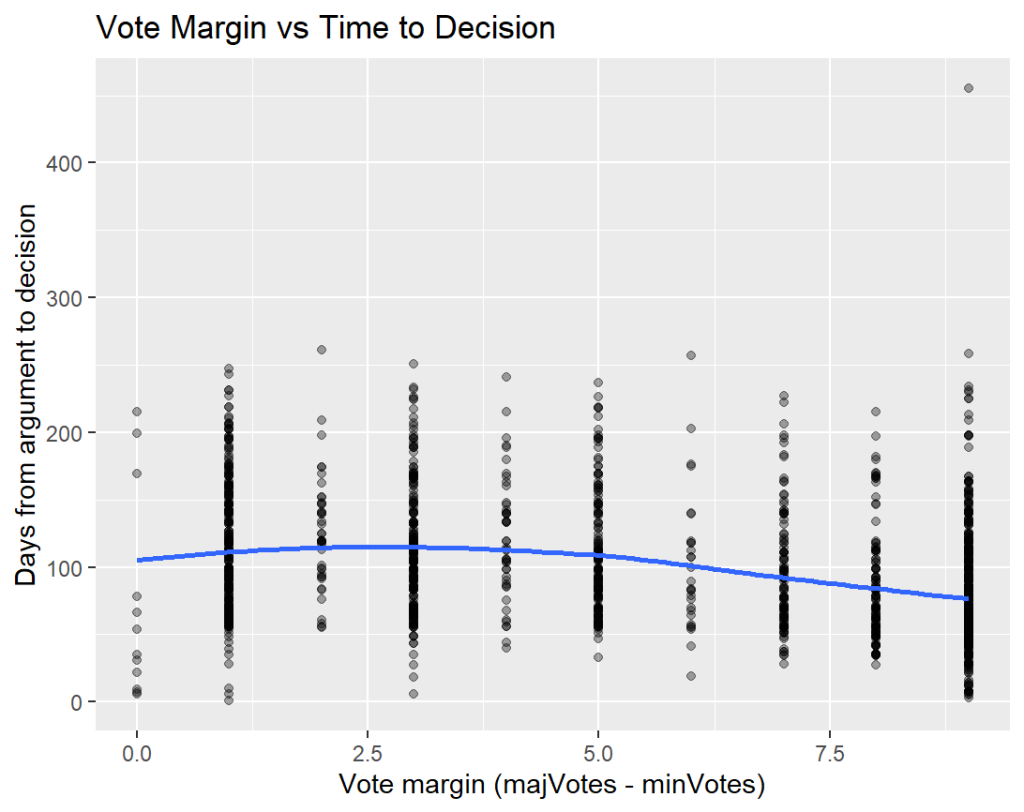

The vote-timing correlation also supports the theory that case complexity drives the lengthening decision timeline. Divided cases typically involve harder questions, more competing interests, and greater difficulty in crafting majority opinions that can hold five or more votes. These cases naturally take longer to resolve, and their concentration at term’s end reflects this reality.

The justice factor: writing speed and assignment patterns

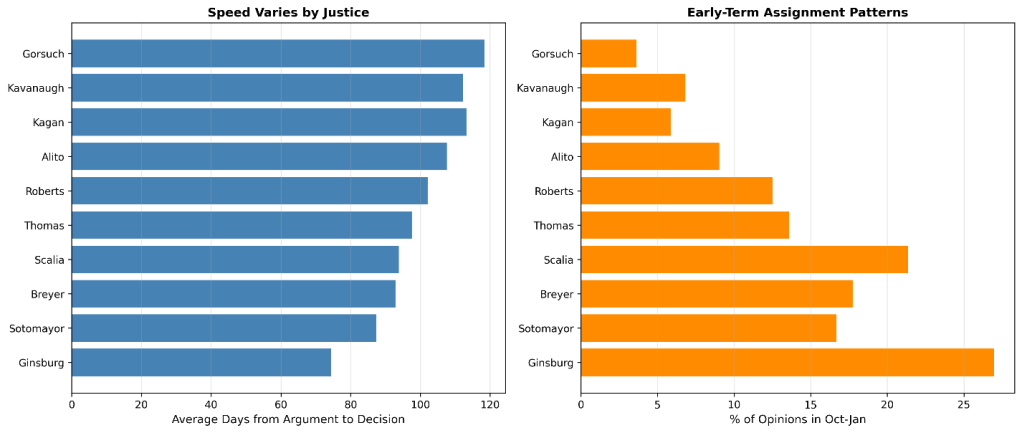

Individual justice patterns reveal striking variations in decision speed that have remained remarkably consistent across multiple terms. Among justices in the dataset who wrote at least 20 majority opinions, the gap between fastest and slowest is dramatic: the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg averaged just 74.4 days from argument to decision, while Justice Neil Gorsuch averages 118.5 days – a difference of nearly six-and-a-half weeks.

The current court shows a clear divide. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, at 87.3 days, produces opinions the fastest among the sitting justices. At the slower end, as noted, is Gorsuch at 118.5 days, followed by Justice Elena Kagan at 113.2 days and Justice Brett Kavanaugh at 112.2 days. Chief Justice John Roberts falls in the middle at 102.2 days, while Justice Clarence Thomas averages 97.5 days.

These patterns correlate with early-term output in revealing ways. Ginsburg authored 27% of her opinions in the October-through-January period, the highest rate in the dataset. The late Justice Antonin Scalia, at 21.4%, and Breyer, at 17.8%, also showed strong early-term productivity. Among current justices, Thomas leads with 13.6% of his opinions coming early in the term, while Gorsuch is at only 3.6%.

The data suggests that some justices either receive – or choose to take –cases that can be resolved quickly and released early. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who averaged a remarkably fast 77.2 days overall, produced 27.3% of her opinions in the first four months of the term. Whether this reflects deliberate assignment strategies by the chief justice, differences in writing style, or the types of cases toward which particular justices gravitate is unclear. But the consistency of these patterns across years indicates they represent genuine differences in judicial approach rather than random variation.

Vote margins and the complexity factor

The relationship between case divisiveness and decision timing reveals one of the dataset’s clearest patterns, mentioned earlier: close cases take substantially longer to decide. Unanimous 9-0 decisions average just 76.6 days from argument to opinion, while 5-4 decisions average 112.7 days. But the pattern is not entirely linear – the longest delays come in two-vote margin cases (125.1 days average) and four-vote margin cases (121.6 days average), suggesting that cases with highly unstable coalitions pose particular challenges.

This timing difference helps to explain the concentration of divided cases at term’s end. If close cases require an extra month or more of deliberation compared to unanimous cases, they naturally migrate toward later months. A case argued in November that might have been decided unanimously by late January will, if closely divided, not appear until March or April. This effect, combined with any strategic considerations about releasing controversial decisions, produces the familiar June crunch of divided opinions.

The vote-timing correlation also appears when comparing early decisions to late ones. Cases decided between October and January show an average vote margin of 7.17, while May and June decisions average only 5.21. More tellingly, 56% of early-term decisions are unanimous compared to just 30.6% of decisions issued late in the term. The court is not just releasing more decisions late – it’s releasing qualitatively different decisions, with different levels of internal agreement and, presumably, different levels of complexity.

Circuit origins and case characteristics

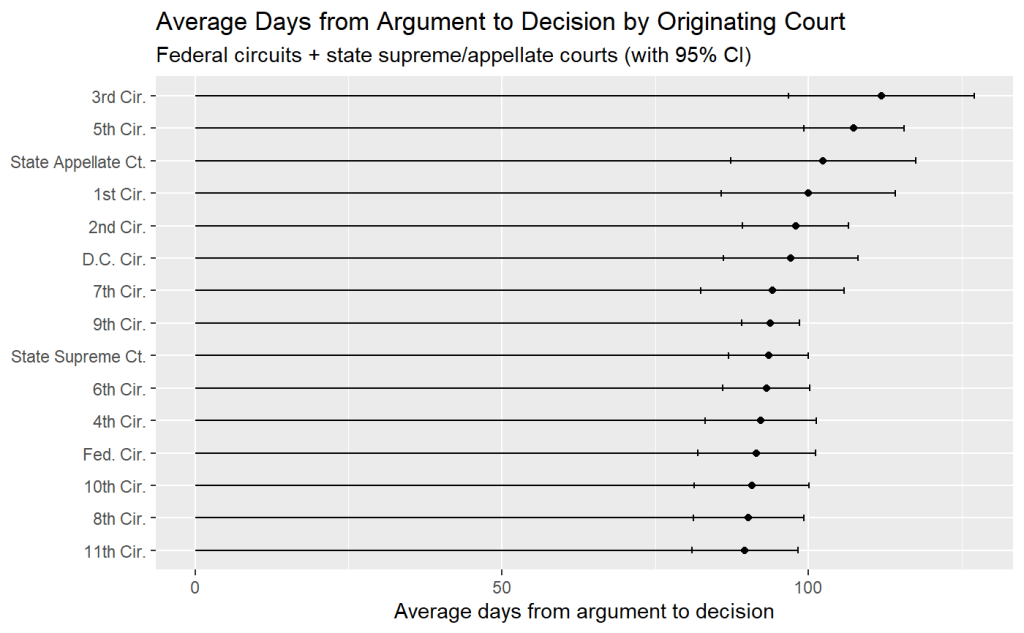

The lower court from which a case arrives also significantly predicts how long it will take the Supreme Court to issue its decision. Cases from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit average 111.9 days from argument to decision, the longest of any circuit. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit follows at 107.4 days. By contrast, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit – despite generating more Supreme Court cases than any other circuit (which is unsurprising, given that it is the largest circuit) – sees its cases decided in an average of just 93.8 days.

These variations likely reflect differences in the types of cases each circuit generates rather than any efficiency or inefficiency of the circuits themselves. The 3rd Circuit’s longer timeline may indicate more complex statutory interpretation cases or novel constitutional questions. The cases hailing from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which average 91.5 days, frequently involve technical patent disputes that, despite their complexity, may present cleaner questions for the Supreme Court to resolve.

State supreme court cases average 93.5 days, faster than many federal cases. State appellate court cases, although representing a smaller sample, average 102.4 days. This difference may reflect the types of cases the court grants from state systems – often involving well-developed constitutional questions with clear circuit splits – compared to the more varied federal docket.

Issue areas and subject matter

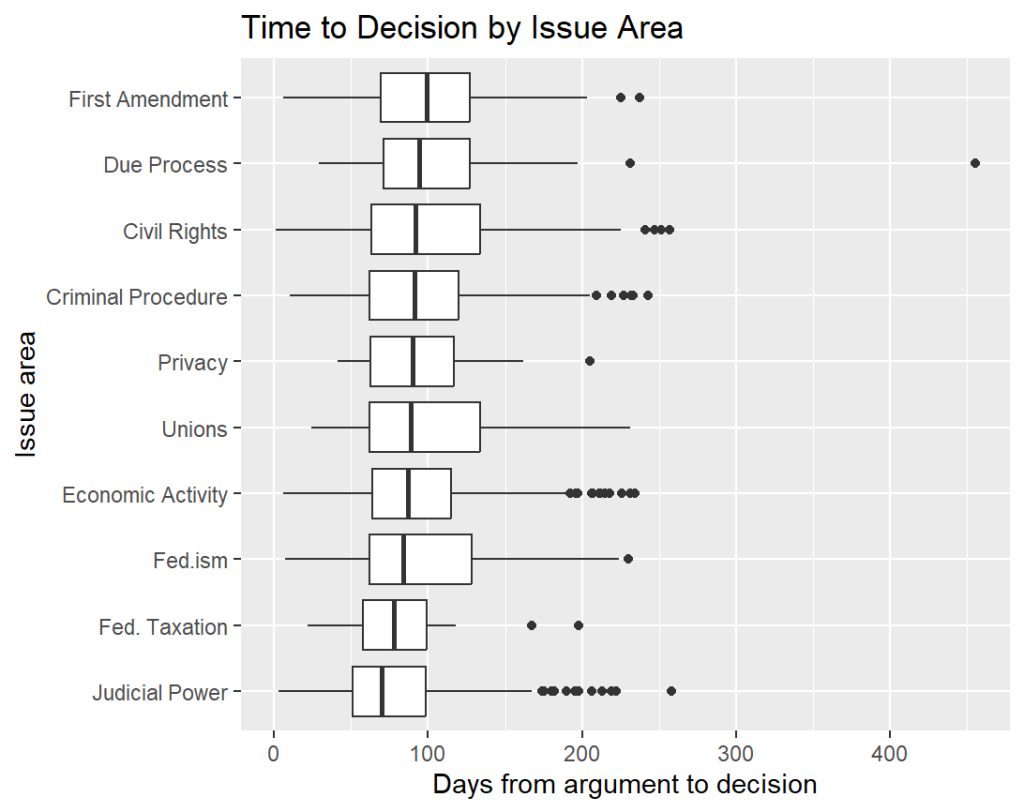

The substantive area of law significantly affects decision timing. Due process cases lead the pack, averaging 110.4 days from argument to decision. First Amendment cases follow at 105.1 days, while civil rights cases average 102.9 days. At the opposite end, judicial power cases – those dealing with the exercise and extent of the judiciary’s authority – average just 81.3 days, and federal taxation cases average 84.6 days.

These variations suggest that constitutional cases, particularly those involving individual rights, require more extensive deliberation than cases involving federal jurisdiction or technical tax questions. Criminal procedure cases, despite their frequency on the court’s docket (414 cases in the dataset), average a moderate 97.3 days to be decided, while economic activity cases average 94.3 days.

The issue area timing differences shown in the graph above may also reflect the political salience of different case types. First Amendment cases often involve contentious questions about speech, religion, or press freedoms that require careful coalition-building. Judicial power cases, by contrast, frequently present more technical questions about standing, mootness, or appellate jurisdiction that, while important, may generate less disagreement among the justices and thus require less time to decide.

Looking forward

The 2025-26 term’s rebound to seven decisions by late January raises the question of whether this represents a return to traditional patterns or merely a temporary deviation. The coming months will clarify whether the court has genuinely shifted back toward earlier releases or whether this term’s early output will prove anomalous as the familiar June crunch returns. What seems certain is that the court’s decision calendar has fundamentally changed over the past decade, with timing patterns revealing as much about the court’s internal dynamics as the decisions themselves.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS, Recurring Columns