Can traditionalism be originalist?

Please note that SCOTUS Outside Opinions constitute the views of outside contributors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of SCOTUSblog or its staff.

Tradition may have been a balancing force in “Fiddler on the Roof” but nowadays it has originalists feeling out of whack. Originalists unite around the belief that constitutional provisions should be interpreted according to their original public meaning; that is, how these provisions would have been understood at the time of their ratification. But what counts as evidence of original public meaning? And can post-ratification practices play a role?

Answering that latter question in the affirmative – looking for evidence of continuous and widespread practices to illuminate a law’s meaning after its passage – has come to be known as legal traditionalism. Leading originalists reject traditionalism or argue that rumors of its influence in recent Supreme Court decisions are greatly exaggerated. But, importantly, the court itself may not have gotten the message: Several recent landmark decisions instruct lower courts to do more than examine the law’s text and the historical context in which that text was ratified. Rather, the court has recognized that judges trying to apply old laws to contemporary disputes must account for long-running and widespread practices that illuminate the relationship between the law and the facts. While those practices may not be definitive, they are to be considered valuable clues regarding what the law has long meant – and therefore what it continues to mean.

This is for good reason. Despite the pushback from certain originalists, there is no betrayal inherent in the turn to traditionalism. Rather, originalism and traditionalism are compatible. So compatible, indeed, that when an avowedly originalist court gets to engage in analysis that cuts to the heart of the originalist project – determining what the law is – it finds traditionalism the best way to do so.

Some background

Originalism arose as a response to judicial misadventures in the mid-20th century, when the Supreme Court interpreted laws ratified in 1789 or 1868 based on contemporary liberal norms. The Sixth Amendment’s right to “the Assistance of Counsel” required states to provide indigent defendants with free legal representation, the court announced in 1963. The First Amendment’s protection of “the freedom of speech” required a complete renovation of defamation law, starting in 1964. Perhaps most infamous was the court’s 1973 declaration that the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause invalidated most state restrictions on abortion.

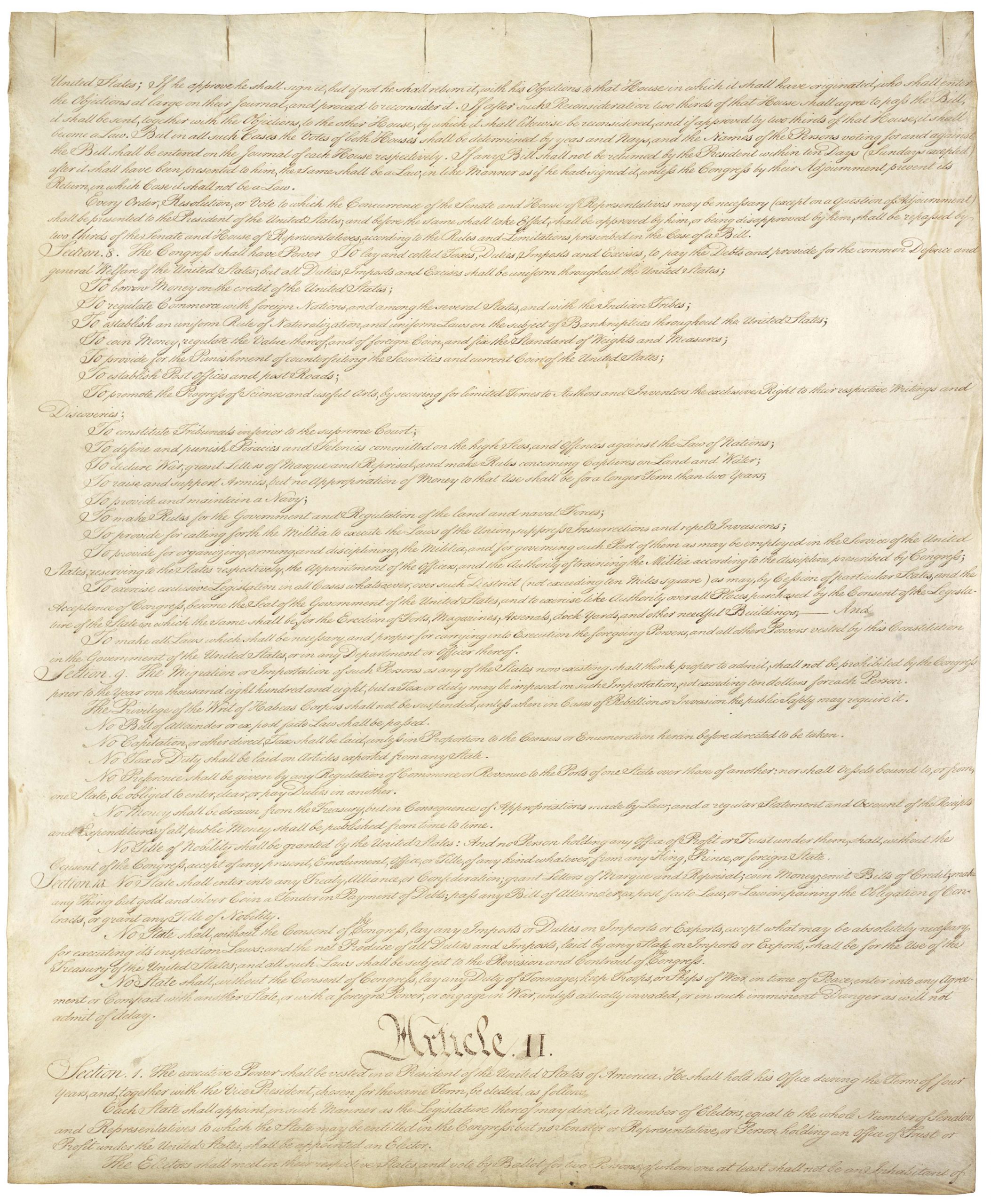

Originalists correctly perceived that this “judicial activism” represented a dangerous overreach. They knew the court was “legislating from the bench,” their go-to accusation, because nobody thought the Bill of Rights had this legal effect for decades, if not centuries. If the Sixth Amendment really meant that public defenders were constitutionally necessary, why did it take nearly 175 years before that argument found purchase (or was even raised) before the Supreme Court? Were Americans violating the Constitution, in myriad ways and unbeknownst to all, that whole time? Of course not. A fundamental tenet of the rule of law, and now the first principle of originalism, is that laws do not change without being changed by prescribed means. Yet without amending the Bill of Rights, which it obviously cannot do, the court changed its effects, deciding that its provisions had meanings incongruous with American traditions.

Originalism was designed to do the opposite; to return unamended law to its original, unchanged state. How precisely to do so is not obvious. Earlier iterations of the theory (and a minority of originalist theorists today) held that judges should look for evidence of ratifiers’ “original intent”; that is, the intent of the ratifiers in passing a particular law. But most originalists now want the Supreme Court to find a constitutional text’s “original public meaning,” or what it would have meant to the American public at the time of its ratification.

More controversial is whether post-ratification practices should factor in when interpreting a specific provision. In other words, should practices that occurred after the provision was ratified inform how its text should be understood? Most public-meaning originalists think that aside from precedent, the answer is no. In their view, using subsequent history unmoors interpretation from the Constitution’s text, whose content is the law as it was understood when passed – and not after.

That said, one exception has gained some momentum. Under the theory of “liquidation,” articulated by Constitutional framer James Madison and revived in recent years, a legal provision may be indeterminate until government officials “liquidate” (that is, determine) its meaning through practice. For example, if federal officials disputing the Sixth Amendment’s meaning in the late 18th century had decided, after deliberating on the question, that they had to provide pro bono representation to indigent defendants, that would be constitutionally valid – and fixed – even if it were not the best construction of the Amendment’s public meaning.

Traditionalism takes things one step further. It suggests that liquidation is on to something, because post-ratification practices tell us how indeterminate text came to govern Americans’ lives. We know the Supreme Court wrongly changed the law in the 20th century because we know what Americans were doing for decades if not centuries before the court decided otherwise. We had traditional practices. Those practices highlight that the unchanged law is not best understood as an abstract idea contained in law’s semantic meaning, or as the domain of government officials, but as something that gives shape to everyone’s behaviors – something that has a legal effect.

Living traditionalism?

Several justices displayed at least some comfort with a traditionalist analysis in the landmark 2021-22 term. Undoing Roe v. Wade, Justice Samuel Alito determined in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that abortion is not “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition” and was therefore not protected under the Fourteenth Amendment. To prove it, Alito examined pre-ratification English common law – perhaps that’s the history element – but also post-ratification state laws banning abortion and other materials that highlighted Roe’s innovation. In Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, Justice Neil Gorsuch employed a more narrative form of traditionalism, appealing to “the Constitution and the best of our traditions” to reject a strict separation between church and state and to argue that religious expression has historically been part of the public square.

Observing this pattern, Notre Dame law professor Sherif Girgis criticized it as “living traditionalism,” decrying the use of “post-ratification practices that do not shed special light on original meaning and do not reflect prior actors’ deliberate efforts to interpret the legal text.” Here at SCOTUSBlog, Girgis’ Notre Dame colleague Haley Proctor has also offered an ongoing critique of traditionalism amidst her superb analysis of Second Amendment cases. In New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that states regulating guns must “demonstrate that the regulation is consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” At first blush, that appears to be a traditionalist test, using longstanding practices as evidence of the Second Amendment’s metes and bounds. With her fellow originalists, however, Proctor disclaims the idea that “popular practices long postdating the ratification of the Constitution can give shape to the rights that this founding document protects.”

To be clear, this does not foreclose traditionalism altogether. The Bruen majority only “rejects evidence of ‘post-ratification adoption or acceptance of laws that are inconsistent with the original meaning of the constitutional text.’” There may be such practices that “supplement the original meaning without contradicting it,” Proctor admits. Perhaps post-ratification practices could, in other contexts or under a different interpretation of the Second Amendment, legitimately shed light on the Constitution’s original meaning.

Law belongs to everyone

Originalism’s great open question is how you figure out what the fixed meaning of a law is. Courts’ routine work entails answering that question by consulting precedent. Most legal questions may be resolved this way; as new laws are integrated into the legal landscape these are immediately shaped, limited, and otherwise interpreted by litigants with reasonable disagreements about what the law now demands. Advocates bring the issues to court, judges answer interpretive questions, and subsequent disputants argue that the precedent is on their side, inapposite to their case, or was wrongly decided.

But what do you do when there is little or no precedent? What if many years have passed, with minimal record of any disputes that might illuminate a provision’s meaning – much less any resolution? Importantly, this does not mean that the now-disputed law has taken on no meaning. It is equally likely that there is no legal precedent because the law’s meaning had long been perfectly clear. So where to look for such potential evidence?

Again, originalism answers that question by pointing judges to the semantic meaning of a provision’s text at the time it was enacted. Historical facts (such as colonial-era practices the provision came to supplant or codify) can supplement this by providing important context.

Yet by focusing on a limited corpus of materials considered good evidence – dictionaries, legal documents, literary materials that have happened to survive history – most public-meaning originalists end up recreating a hypothetical version of original meaning: What would this law have been understood to mean? That is not a bad inquiry. It’s certainly better than a judge consulting his moral intuitions. But it doesn’t quite answer the real question at issue, which is, what was this law understood to mean?

Contemporaneous evidence of actual understanding best answers that question. It would be nice to have explicit declarations from well-respected figures saying, “we have just ratified the Sixth Amendment, understanding that it requires states to provide lawyers to indigent defendants” while would-be opponents concede defeat on the record. But such evidence is hard to come by. Fortunately, there are other indications of how the law-abiding public understood the law. And here, practices that emerge after a law’s ratification can be helpfully revealing. We know how Americans understood the Sixth Amendment as it regards the right to counsel, for example, because for nearly two centuries we all behaved as though it did not include an entitlement to state-sponsored legal representation.

Indeed, traditionalism’s great insight, drawing on the common-law system, is that those who live under law’s rule interpret the law all the time. When a new law passes, we must conform our conduct to its demands, in combination with the many laws already governing us. We consult our lawyers and use our common sense. Disputes arise and resolve as sensible interpretations prevail. Through millions of individual acts – advice, lawsuits, adjustments to business practices, government enforcement – the legal system reaches equilibrium. Meaning is no longer contested, and a law’s meaning crystallizes. The process takes some time, and it’s not quite clear in the moment that the process has produced a final, fixed meaning. But a judge looking back and seeing an uninterrupted course of practice, done openly and without legal challenge, can safely conclude that Americans considered that practice consistent with the law’s demands.

A more perfect originalism?

This kind of analysis – which accepts the need for post-ratification practices – requires inquiries into not just legal history but social history. And to be sure, it presents plenty of theoretical and practical challenges. Rigorous academic history requires time, materials, and epistemic humility. It is hard to know when a practice was treated as a constitutional right, and when it was considered merely acceptable. Judges and academics will have to develop more detailed frameworks for analyzing evidence.

But these are challenges with analogs in all history-based modes of analysis. Judging, for those who believe that the law has a fixed meaning, is all about synthesizing evidence from the past and pronouncing a conclusion about where it points. If the alternative is judging cases by unspoken appeal to normative views of good governance, the choice is clear. Judges are much better prepared to assess and synthesize history than they are to make moral judgments, and they are at least arguably authorized to do so. As arch-originalist Justice Antonin Scalia put it, “the principles adhered to, over time, by the American people,” should provide color to indeterminate constitutional provisions, as opposed to the “philosophical dispositions of a majority of this Court.”

That stalwart originalist justices started invoking tradition at the height of originalist achievement should not be baffling. Originalists have been saying for decades that judges ought only say what the law is, never what the law should be. Traditionalists, who distinguish what the law is from what the law would have meant, have a strong case for being that mantra’s truest adherents.

Posted in SCOTUS Outside Opinions

Cases: Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. Bruen, Kennedy v. Bremerton School District