The passage of time

Courtly Observations is a recurring series by Erwin Chemerinsky that focuses on what the Supreme Court’s decisions will mean for the law, for lawyers and lower courts, and for people’s lives.

Please note that the views of outside contributors do not reflect the official opinions of SCOTUSblog or its staff.

When is it ever appropriate for the Supreme Court to decide that a federal law is unconstitutional because it is no longer needed?

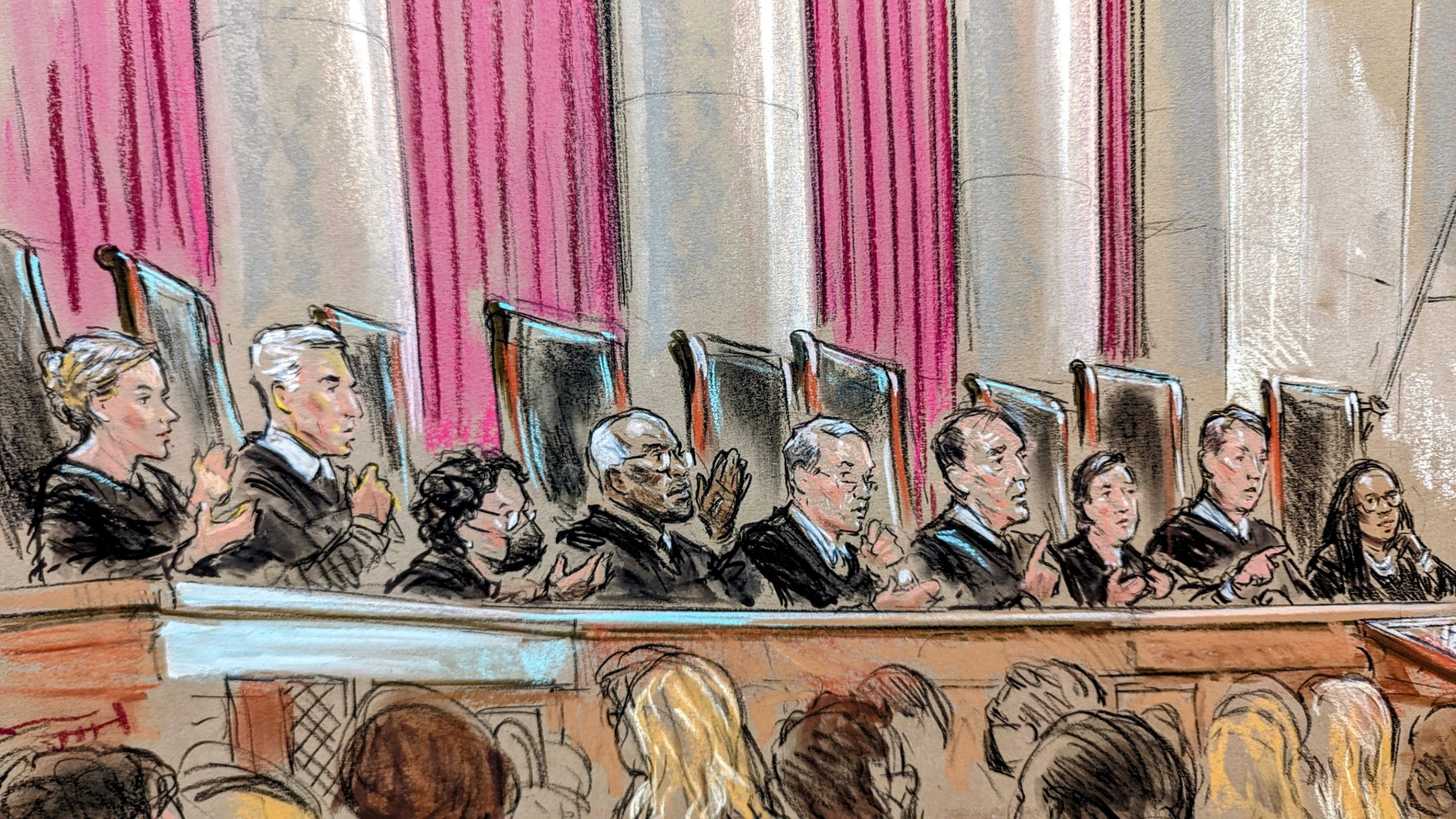

This question arose during the oral arguments on Oct. 15 in Louisiana v. Callais, involving the constitutionality of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits election standards and practices that have a discriminatory effect against minority voters. And it was at the heart of the court’s decision over a decade ago in Shelby County v. Holder, which effectively struck down another crucial part of the Voting Rights Act that required jurisdictions with a history of race discrimination in voting to obtain federal preapproval before making significant changes to their election systems. But it is not obvious why it is the court’s job to decide when a problem is over, and it is even less clear how the court should go about making such an inquiry.

The focus on the passage of time and change

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, which sought to remedy longstanding pervasive racial discrimination in voting, is one of the most important civil rights laws ever adopted in the United States.

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act provides that jurisdictions with a history of race discrimination in voting may change their election systems only if they get “preclearance” from the attorney general or a three-judge federal district court. Section 4(B) of the Act defines those jurisdictions that must get preclearance because of their history of race discrimination in voting.

Each time the preclearance requirements were about to expire, Congress extended them. In 1982, Congress held extensive hearings, modified the formula under Section 4(B) of the act, and extended its provisions for another 25 years. Before the requirements were set to expire in 2007, Congress held 21 hearings and produced a record that is over 15,000 pages. The Senate voted 98-0 to extend the law for another 25 years; there were only 33 “no” votes in the House of Representatives. Then-President George W. Bush signed the extension into law.

Yet in Shelby County v. Holder, in 2013, the court, by a vote of 5 to 4, held Section 4(B) unconstitutional and thereby also effectively nullified Section 5, which applies only to jurisdictions covered under Section 4(B). It was the first time since the 19th century that the court declared unconstitutional a federal civil rights statute.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the court and stressed that the formula in Section 4(B), last modified in 1982, rests on data from the 1960s and 1970s and that race discrimination in voting has changed since then. The court declared: “Nearly 50 years later, things have changed dramatically. Shelby County contends that the preclearance requirement … is now unconstitutional. Its arguments have a good deal of force. In the covered jurisdictions, ‘[v]oter turnout and registration rates now approach parity. Blatantly discriminatory evasions of federal decrees are rare. And minority candidates hold office at unprecedented levels.’ The tests and devices that blocked access to the ballot have been forbidden nationwide for over 40 years.” Thus, “[c]overage today is based on decades-old data and eradicated practices.” In other words, the court’s sense of the passage of time and the changes in society led to its conclusion that the formula in Section 4(B) was unconstitutional.

The other central provision of the Voting Rights Act is Section 2, which Congress amended in 1982 to provide that disparate impact (that is, seemingly neutral policies that result in negative effects on a particular group) can be used to prove racial discrimination; proof of discriminatory intent is not required. In Allen v. Milligan, in 2023, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, in a concurring opinion, remarked, “even if Congress in 1982 could constitutionally authorize race-based redistricting under § 2 for some period of time, the authority to conduct race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future.” At the Oct. 15 oral argument in Louisiana v. Callais, Kavanaugh again raised this issue and said: “[T]his Court’s cases in a variety of contexts have said that race-based remedies are permissible for a period of time, sometimes for a long period of time, decades in some cases, but … they should not be indefinite and should have a[n] end point.”

It is hard to think of other instances in which the Supreme Court has indicated that government actions that were constitutional have become unconstitutional because of the passage of time and changes in circumstances. There was the enigmatic comment in Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s majority opinion in the 2003 case of Grutter v. Bollinger, which upheld the University of Michigan Law School’s affirmative action program: “We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.” But why, as was asked at the time, 25 years? And did this mean that the court thought that affirmative action programs then would be unnecessary or that they would become unconstitutional? (In fact, less than 25 years later, in 2023’s Students for Fair Admission v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, the court effectively overruled Grutter and declared affirmative action by colleges and universities unconstitutional.)

Why and how?

Why should the court, rather than Congress, decide whether a problem remains and whether a law still is needed? In Shelby County, for example, why does it matter whether Congress relied on old data in voting overwhelmingly to extend the preclearance requirements of the Voting Rights Act? Nothing in the Constitution requires that Congress have data, let alone recent data, to support its legislative decisions.

The implicit answer in Shelby County was that the preclearance requirement intruded on state sovereignty and, to justify this burden on states, there had to be sufficient proof to support a compelling interest. But in New York v. United States, the seminal contemporary case reviving the 10th Amendment as a limit on congressional power over the states and preventing Congress from forcing them to enact or enforce federal law, the court declared: “No matter how powerful the federal interest involved, the Constitution simply does not give Congress the authority to require the states to regulate.” So if Shelby County was about state sovereignty and the 10th Amendment, it is unclear why it was a matter of proof of a current problem at all. In other words, either Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act is forcing states to regulate and therefore unconstitutional regardless of the evidence, or it is not forcing to states to regulate and therefore it does not violate the Constitution.

Also in Shelby County, Roberts’ majority opinion said that the preclearance requirement violated the principle of equal state sovereignty, the requirement that Congress must treat all states the same. But it is entirely unclear where this principle comes from: it is not in the text of the Constitution and was rejected by the Congress that ratified the 14th and 15th Amendments, which significantly limited the power of the states. Even if such a principle exists, the court failed to explain why it could be overcome by Congress relying on different evidence in extending preclearance.

Likewise, for Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, it is puzzling why the court should decide when it is no longer needed. The implicit argument is that avoiding disparate impact liability requires consideration of race, such as in drawing election districts, and this is allowed only if there is proof of a compelling government interest. But Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson addressed this directly when she said at oral argument that Section 2 “is not a remedy in and of itself”; it is instead “the mechanism by which the law determines whether a remedy is necessary” – which, she stated, may or may not involve the consideration of race. “And so that’s why it doesn’t need a time limit, because it’s not doing any work other than just pointing us to the direction of where we might need to do something.”

Underlying all of this is a basic question: if the court is to decide whether a remedy is no longer needed, how should it go about making that determination? This is a factual question as to whether a problem remains sufficiently serious to justify the law. One answer is that the court should defer to Congress in answering this factual inquiry, especially in light of Congress’ expansive powers under Section 5 of the 14th Amendment and Section 2 of the 15th Amendment, which empower Congress to enact laws to enforce these two constitutional amendments.

But if the court rejects such deference to Congress, then there must be a basis for the justices deciding the level of racial discrimination in voting sufficient to justify the provisions in the federal law and also for its determining whether that threshold is met. The problem, though, is that the justices seem to be relying on their own sense of race discrimination in voting rather than actual evidence. There is not a factual record in this case as to the current extent of race discrimination in voting, leaving the justices to rely on their own intuition (and biases) about whether there continues to be a problem and if so, its severity.

It always should be troubling for the court to decide empirical questions without actual evidence. But it should be especially disturbing for the court to strike down or narrow a vital civil rights statute based on a group of justices’ intuition that race discrimination in voting is largely a thing of the past.

Posted in Courtly Observations, Recurring Columns

Cases: Shelby County v. Holder, Allen v. Milligan, Louisiana v. Callais (Voting Rights Act), Louisiana v. Callais