Life, Law & Liberty: confessions of a judicial introspectionist

Please note that the views of outside contributors do not reflect the official opinions of SCOTUSblog or its staff.

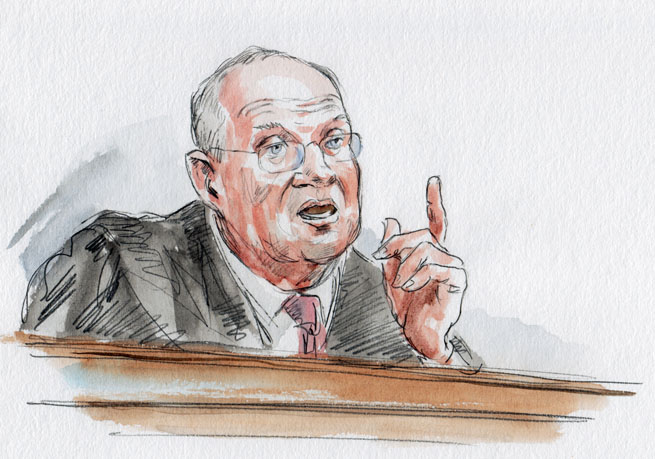

Life, Law & Liberty, Justice Anthony Kennedy’s memoir, was published earlier this month. The prose is simple and direct, and the book is a worthwhile read. Although Kennedy is not as colorful as my old boss, Justice Antonin Scalia, he has some good stories to share. He also defends his major decisions and his method of constitutional interpretation. I suspect many readers will find his approach to the law pretty unsatisfying in this day and age. But I also suspect most readers will admire his old-school empathy and ethical prudence. In many ways, Kennedy is of a different time.

The book’s first two parts – “Life” and “Law” – recount his time before joining the Supreme Court. Kennedy grew up in Sacramento with a father who was a lawyer and a mother who was a civic advocate. He took over his father’s law practice after his father died at the age of 61; after that, Kennedy was basically a small-town lawyer until he was tapped by President Gerald Ford for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit.

Kennedy emphasizes throughout the book how growing up in the West influenced his affinity for liberty. He paints a fairly idyllic picture of the West, albeit one interrupted by racial discrimination during World War II. Here, Kennedy tells a particularly poignant story about how one of his young childhood friends disappeared to the internment camps and was never seen again. He tells another about how his father refused to take advantage of the missing Japanese Americans to buy a farm.

Other stories in the book are less sentimental. Kennedy got a big scare after he came home to a ransacked house after ruling on the 9th Circuit in a case involving a follower of Charles Manson. He was on the 9th Circuit panel that ruled in favor of Jagdish Rai Chadha in the famous INS v. Chadha case, which held that the one-house congressional veto in the Immigration and Nationality Act was unconstitutional, and later ran into Chadha at a record store: Chadha was the cashier, and, once Chadha recognized him, offered him free CDs; Kennedy declined the gift. Later in the book, he also has great stories about meeting Vladmir Putin and Xi Jinping.

One of the themes of the book is how important his family is to him – he lost his sister, mother, and brother all within an 18-month stretch – and how they instilled in him a sensitivity to discrimination and a desire to do the right thing. Although some of this comes off as a little too precious, it was refreshing – in our day of judicial spouses flying provocative flags and texting about election litigation – to learn that Kennedy’s wife turned down a job in the Reagan administration when they moved to Washington, even though they needed the money, and how the two of them never, ever discussed cases.

The last part of the book – “Liberty” – is about Kennedy’s time on the court. He was the last justice unanimously confirmed to the Supreme Court, and he recounts the story about how he got the job after the first two nominees (Robert Bork and Douglas Ginsburg) flamed out. Kennedy spends most of this part defending his judicial record, including his opinions in Bush v. Gore (he discloses he was primary author of the court’s unsigned opinion), abortion cases, death penalty cases, free speech cases (including the landmark campaign-finance case Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission; I had forgotten he had authored that one), and gay rights cases. Some of these chapters include coda to demonstrate that time has proven him right: for example, he catches up with the inmates he spared and he revisits the ballot-box post-mortem on the 2000 election.

But deeply unsatisfying is his explanation of how he decided these cases. What he says in the book pretty much matches how we saw him in the Scalia chambers: in Kennedy’s view, if a judge is introspective enough (he has an entire chapter on introspection) – for example, studies the law thoroughly enough and reflects on “who am I” often enough (he invokes that phrase over and over again) – the right answer will magically appear before him. It’s not judicial activism; it’s judicial introspectionism.

Although Kennedy says this method falls somewhere between originalism and pragmatism, it sounds much closer to pragmatism than to originalism. He talks a lot about liberty, human rights, and, perhaps most of all, “dignity.” (My Federal Courts classes sometimes chuckle at his invocation of the “dignity” of the government in sovereign immunity cases; do governments have feelings, too?) He also talks a lot about how our understandings of these concepts evolve over time. But Kennedy doesn’t say much about how only one of these words – liberty – actually appears in the Constitution or how the Constitution says even liberty can be taken away so long as we give you “due process” before doing so. Nor does he say anything about the other mechanism we have to capture societal evolution: our periodic elections of representatives to the other branches of government. For example, when he defends his gay rights opinions, Kennedy compares our evolution on gay rights to our evolution on slavery. But he leaves out that we ended slavery by amending the Constitution, not by judicial introspection.

Throughout his discussion of these cases, Kennedy rightly uses Scalia as his foil: they were about as opposite as you could get in both method and temperament. (I have a hard time believing Kennedy’s recollection is accurate that Scalia told him Griswold v. Connecticut was correctly decided.) Indeed, some of the most uncomfortable parts of the book are when he recounts some of the harsh words Scalia had for his opinions. Kennedy says they were friends, and I do not doubt this was true, but I know he frequently perturbed Scalia. Unlike the other swing vote back then, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who tended to make up her mind and stick to it, the judicial introspectionist is always susceptible to changing his mind after a restless night of sleep. So it was with Kennedy.

Yet, one of the most moving stories of the book is when Scalia came to Kennedy’s office shortly before his death to apologize for the harsh language in his dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges. Kennedy says Scalia had seemed down for months after that dissent and they did not talk much thereafter. But they eventually, and unexpectedly, reconciled, and Scalia’s wife called Kennedy after Scalia died to tell him that Scalia was “happier than he had been in months” after their reconciliation. Kennedy reminds us that life is too short for grudges.

I was surprised by two things in – or, in one case, not in – the book. First, I am admittedly biased, but I was surprised how little Kennedy says about his law clerks. Although he lists them all in the appendix, he doesn’t say much about them. He says a little about a law clerk who let him borrow an apartment when he arrived in Washington; he says a bit about the law clerks who are now justices themselves (Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavannagh); and he discusses research from Professor Dan Epps. But that’s pretty much it. He also acknowledges that he let his law clerks do first drafts of his opinions, but he insists he drafted “the substantive parts” himself.

Second, I was surprised how much of the book was devoted to his love of teaching. Kennedy was an instructor – I assume an adjunct professor – at McGeorge School of Law while he was in Sacramento and continued to teach for it in Europe during the summers after he joined the court. He describes his teaching methods in great detail – including his use of the Socratic method – and, indeed, one of the longest chapters in the book is about teaching. I got the impression that he might have enjoyed his time in the classroom even more than his time on the bench or in practice.

In the end, readers will undoubtedly conclude that Kennedy is a very decent man. But I doubt they will conclude that judicial introspection is much of a method of constitutional interpretation. If we aren’t quite all originalists now, we are pretty close.

Posted in Book Reviews