The lone wolf

In Dissent is a recurring series by Anastasia Boden on Supreme Court dissents that have shaped (or reshaped) our country.

Please note that the views of outside contributors do not reflect the official opinions of SCOTUSblog or its staff.

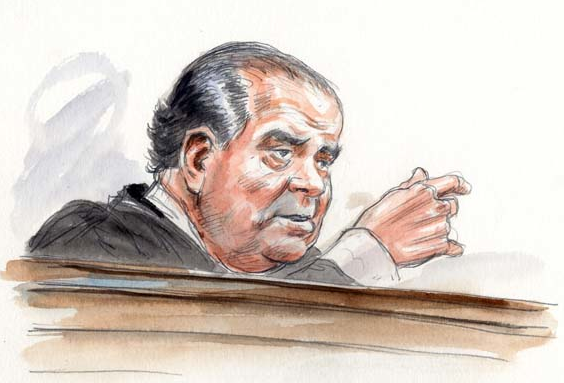

It became one of the great “I told you so” moments in Supreme Court history. Justice Antonin Scalia, dissenting alone in Morrison v. Olson, warned that letting Congress chip away at executive power in favor of unelected bureaucrats would come back to bite us – while giving us one of the most memorable judicial lines of all time. Forty years later, for better or worse, the court may finally be ready to follow his lead.

A law for the times, not the Constitution

Morrison involved the Ethics in Government Act of 1978, a post-Watergate reform measure aimed at restoring public trust. After President Richard Nixon fired the man investigating him, Congress sought to create a new framework for pursuing potential ethical violations. The EIGA created a special court and empowered it to appoint an “independent counsel,” who was further empowered to investigate and prosecute high-ranking officials. This counsel wasn’t subject to normal executive oversight, as would be a typical prosecutor. Instead, she could be removed only by the attorney general for “good cause” or other listed reasons – not, as would be the default, at the president’s discretion.

In 1986, Alexia Morrison was appointed as independent counsel to investigate Ted Olson, then assistant attorney general in the Reagan administration. The dispute began after Congress demanded that the Environmental Protection Agency turn over documents related to the Superfund program – a massive pot of money meant to help clean up toxic waste sites. Members of Congress suspected that the Reagan administration, and in particular, EPA administrator Anne Gorsuch Burford (yes, Neil Gorsuch’s mother), had mismanaged the program and withheld documents for political reasons.

As legal advisor to the president, Olson had recommended that the EPA assert executive privilege. In response, congressional Democrats cried obstruction and perjury. Eventually, Morrison was appointed as independent counsel and she subpoenaed Olson. He refused to comply on the basis that restrictions on the president’s ability to remove Morrison – effectively, an unelected functionary – rendered her office unconstitutional.

The court before Morrison

To understand Olson’s argument, it helps to review the court’s evolving interpretation of the president’s removal power. Other than impeachment, the Constitution is largely silent on removal. But in the famous “Decision of 1789,” the first Congress concluded after heated debate that the president must be able to unilaterally remove executive officials – not because the Constitution says so explicitly – but because political accountability demands it. The president, unlike others in the executive branch, is elected. If the buck is to stop with him, he must control anyone who wields executive power. And firing, of course, is the ultimate means of control.

That principle was affirmed in 1926 in Myers v. United States, in which Chief Justice (and former President) William Howard Taft wrote that the president had exclusive removal power over purely executive officers. But just nine years later, the court shifted. In Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, it upheld limits on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ability to remove members of so-called “independent agencies.” The court reasoned that these new bodies were not “units in the executive department,” but performed “quasi-legislative” and “quasi-judicial functions.” Independence from the president, once seen as an impediment to an effective and accountable chief executive, was rebranded as a virtue.

This empowered what is known as the administrative state. In the wake of Humphrey’s Executor, Congress increased the number of agencies filled with unelected bureaucrats and insulated them from executive oversight. These agencies had – and continue to have – incredible power over our lives, determining everything from the milkfat in our ice cream to the flow rate of our dishwashers.

Indeed, there’s no definitive account of just how many executive agencies now exist, nor how many regulations they’ve passed. When the Office of Management and Budget recently asked federal agencies to put their guidance documents online, they reportedly refused for no other reason than they didn’t know where to find all of them. Proponents say these agencies need independence so they can exercise expertise free of partisan politics. But to critics, these agencies represent a fourth branch of government – and one that lacks any meaningful political accountability.

Humphrey’s Executor, at least, ruled that the president didn’t require removal power because those agencies weren’t performing traditional executive tasks. But in Morrison, the court was asked how to evaluate removal protections for what many see as a core executive function: the power to prosecute.

The lone wolf

In a 7-1 opinion written by Chief Justice William Rehnquist (Justice Anthony Kennedy was recused), the court upheld the Ethics in Government Act. Humphrey’s Executor, it said, hadn’t hinged on the nature of the agency, but rather on the extent to which Congress had usurped the president’s ability to do his job. Just as the ability to remove quasi-judicial, quasi-legislative officers is not necessary for a president to be effective, neither is the ability to remove independent counsel, even if that counsel is capable of prosecuting people.

Scalia would have none of it.

His dissent – during just his second year on the court – was unrelenting. Reading from the bench, he called the case “one of the most important opinions the Court has issued in many years.” Though some would see the case as a political skirmish with no immediate effect on their lives –after all, it didn’t involve flashy constitutional rights, like freedom of speech or freedom of religion – “[i]n the dictatorships of the modern world, Bill of Rights are a dime of dozen.” According to Scalia, what makes our government special is its structure, which is designed to protect liberty by diffusing power among the different branches.

This case, he said, was about “power,” and power is a zero-sum game. Congress and the executive had sparred, and now an unelected special prosecutor, unmoored from any influence by the Department of Justice or even the president (who had been elected), was wielding the awesome power to prosecute high-ranking executive officials. In short, Congress had forced the Justice Department to surrender its prosecutorial discretion to someone else, who was neither voted into office nor could be easily removed by the person who had been.

“Frequently an issue of this sort will come before the Court clad, so to speak, in sheep’s clothing,” Scalia wrote. “But this wolf comes as a wolf.”

To Scalia, the issue was not about figuring out whether the removal restrictions had gone too far (which he said was “not analysis,” but rather “ad hoc judgment”). Instead, Article II vests the entirety of executive power in the president. If prosecution is a purely executive function, then any law that denies the president exclusive control over it violates the Constitution. This is sometimes referred to as the unitary executive theory, and it has come up in cases regarding executive privilege, presidential immunity, and Congress’s delegation of its law-making power to executive agencies. Proponents, including Alexander Hamilton, have argued that putting the whole of executive power in a single executive has the counterintuitive effect of safeguarding liberty, since it makes it easier to track, criticize, and ultimately vote out that one person. In other words, believers in the unitary executive theory (at least in its purest form) are obsessed not with presidential power but democratic accountability.

In Morrison, the majority tried to gloss over concerns that limiting the president’s removal power undermined political accountability by noting that the attorney general could still remove the independent counsel “for cause.” But Scalia wasn’t impressed. “This is somewhat like referring to shackles as an effective means of locomotion.” What was long recognized (and in fact heralded) as an impairment to executive power could not be rebranded as an important means of executive control.

Invoking his own experience in the Department of Justice, Scalia emphasized that prosecution is a tremendous and weighty power. And the reality is, whether because of scarce resources, or national security, or because justice so requires, prosecution requires discretion. While there’s a real danger that prosecutors will move forward against people they don’t like (or refuse to prosecute people they do), the check on that potential abuse has always been political; The public can vote out a president who mishandles his obligations. But now, Congress had effectively transferred prosecutorial discretion to an official answerable to no one. The majority, he said, had given “shoddy treatment” to both precedent and Article II. “[O]ne must grieve for the Constitution.”

What became of the cast?

Alexia Morrison concluded her investigation without bringing charges, and Congress let the independent counsel provision expire after it was occupied by Ken Starr during the Clinton administration. Turns out, an unaccountable special prosecutor is less appealing when it’s wielded against your guy.

Ted Olson went on to become solicitor general under George W. Bush, a role at the core of executive power. He also became one of the most respected legal conservatives in America, arguing several Supreme Court cases in private practice and representing Tom Brady during “Deflate-gate.” Scalia, of course, became a legendary dissenter.

And for a while, the enduring winner was a fourth branch within the executive branch, which enjoyed the power to promulgate rules with enormous effect on American’s everyday lives, to enforce those rules, and to adjudicate prosecutions using in-house tribunals – sometimes with removal protections, effectively insulating them from executive oversight.

But the tide may finally be turning against the administrative state.

In the decades after Morrison, the court has gradually chipped away at that decision’s foundations. In 2010’s Free Enterprise Fund v. PCAOB, the court invalidated a scheme of double removal protections, wherein board members were removable “for cause” by another agency member, who also was only removable “for cause,” ruling that such double insulation from the president exceeded even what was allowed in Morrison and thus giving the president more influence over agency members. In 2020, in Seila Law v. CFPB, the court struck down for-cause removal protections for the head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, reasoning that the board of that agency looked nothing like the one in Humphrey’s Executor and its officers wielded more power than the special counsel did in Morrison. One year later, in Collins v. Yellen, it held the same for the Federal Housing Finance Agency. Thus, in each of these cases, the court chose to empower the presidency over various administrative agencies.

And just weeks ago, the court issued a decision on its emergency docket, involving a dispute that arose after President Donald Trump fired members of the National Labor Relations Board and the Merit Systems Protection Board despite statutes saying they could only be removed “for cause.” The employees asked to be reinstated while the case makes its way through the courts – but the court declined. In her own memorable dissent, Justice Elena Kagan wrote: “Today’s order favors the President over precedent.” A fitting echo of the old debate.

The question now is not whether Morrison will be remembered; it’s whether its dissent will become the majority. If it does, it will mark one of the great reversals in Supreme Court history – and represent a posthumous triumph for Scalia over the wolf he believed Congress had let loose.

Anastasia Boden is a Senior Attorney at the Pacific Legal Foundation, where she brings civil rights lawsuits that advance the Constitution’s promises of equality and economic opportunity. She also writes the biweekly newsletter, SCOTUS Scoop.

Posted in In Dissent, Recurring Columns