The consummate public servant

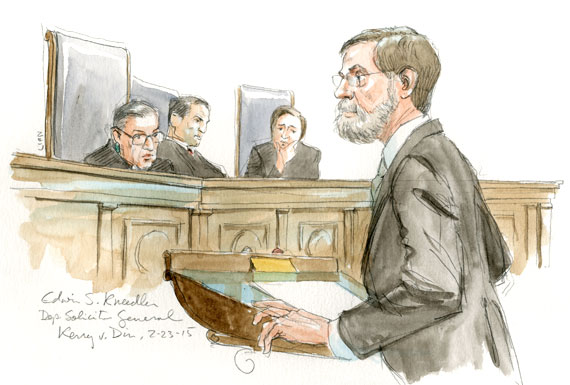

On April 23, 2025, United States Deputy Solicitor General Edwin S. Kneedler made his 160th argument before the Supreme Court, following which he will be retiring. This article is one in a series of tributes from Mr. Kneedler’s former colleagues on his remarkable career.

Edwin Kneedler was the very model of a public servant. His career at the Justice Department spanned nine presidential administrations and coincided with remarkable changes in constitutional law and statutory interpretation. The Constitution as interpreted by the courts is very different today from what it was in the final years of the Carter administration. When Ed joined the Justice Department, Antonin Scalia was a law professor, Sandra Day O’Connor was a state-court judge, and John Roberts was graduating from law school. Courts still looked to the legislative history as often as the statutory text and interpreted statutes consistent with their remedial purposes, the wall of separation between church and state was high, and executive power was near its post-Watergate nadir. All of that changed over the course of Ed’s career.

Ed was no mere bystander to all this dramatic change. Over his remarkable career in the solicitor general’s office, Ed took the podium to represent the United States 160 times, a modern record. In each case, he defended the position staked out by the executive branch with great skill and complete candor. But for every lawyer in the office, Supreme Court arguments are just the tip of a proverbial iceberg – the most public role, but by no means the most time consuming or important work the lawyer performs. The day-to-day work of the office involves editing briefs and making recommendations on which government cases to appeal or to drop. The unseen bottom of Ed’s iceberg was far larger than anyone else’s.

The rules and time constraints for oral arguments and briefs are uniform and certain. Everyone gets 30 minutes a side or 15,000 words. But there are no set rules for how long an assistant to the solicitor general can spend on a memo recommending an appeal or how much time a deputy solicitor general can spend in annotating that memo or providing guidance to the lawyers in the litigating divisions outside the solicitor general’s office about the brief if an appeal is authorized. Most deputies kept their input down near the manageable minimum. After all, appeal recommendations come at a deputy fast and furious, with approximately 500 for each deputy every year. Ed always gave maximum effort. He would not only annotate the recommendation memo in his inimitable scrawl, but he would provide specific guidance on the lower-court briefing. He employed the same hands-on approach to merits briefs and all the other work of the office. Ed did not take many days off, but he never took a case off. There were no unimportant cases in Ed’s view, and he took particular effort to get the government’s position right on issues that were technical or obscure. Indeed, Ed recognized that it was on those issues that the government’s position could carry the most weight, and so it was particularly important to get the government’s position exactly right.

By the time I first had the privilege to work with him, Ed was still in the first half of his remarkable career at the Justice Department. But it did not feel that way. With over 20 years of service under his belt, he was already the institutional memory of the office and the keeper of its best traditions. As someone new to the office, he was an invaluable resource. When I thought I was confronting some novel issue of administrative law or executive authority, it was both humbling and reassuring to run the issue by Ed, and watch him, with a twinkle in his eye, retrieve a brief from the depths of his file cabinet that he had written a decade earlier that thoroughly addressed the issue. And that twinkle was virtually always in Ed’s eye. The man’s middle name is Smiley, after all. Despite the long hours he worked on often contentious issues, Ed kept an even keel and a sense of humor. My experience was hardly unique. An entire generation of OSG lawyers, from Bristow Fellows to newly confirmed solicitors general, learned their trade and were introduced to the traditions and rhythms of the office by Ed. That is a contribution to the rule of law that will continue to pay dividends for decades to come.

In my years since leaving the office, I watched Ed operate from the other side of the table as I came into the office seeking the government’s support on a pending cert petition or a recently granted case. In that context, Ed’s amazing institutional memory was on full display, as was his dedication to getting the United States on the right side of the “v.” It is typical for the deputy with substantive responsibility over an issue to run such meetings, but not every deputy approaches the meetings in the same way. Ed ran his meetings far more like moot courts than any ordinary government meeting. Ed was already thinking ahead to a potential Supreme Court argument and how he would best answer some of the hardest questions on either side of the case. On a number of occasions since I left the office, I had the great privilege of sharing time with Ed at the podium on the same side of the case, including in what turned out to be Ed’s antepenultimate argument before the court. It was an extra pleasure to divide an argument with Ed, because I knew it would involve not just the usual moot courts, but a weekend call or two to discuss the intricacies of the case. Plus, there was no better feeling – or greater advantage for a client – than being able to argue a case with the United States and Ed at your side.

As has been widely reported and remarked, when Ed gave his final argument before the Supreme Court he was greeted with an unprecedented standing ovation. I was not surprised. Over half the court served alongside Ed in the office of the solicitor general or the Justice Department. More to the point, every member of the court heard Ed argue cases with complete candor and dedication to the long-term interests of the United States. He was an embodiment of the rule of law and what it means to be an officer of the court. For his four-and-a-half decades of dedicated public service, Ed deserves a standing ovation from all of us.

Paul Clement is a partner at Clement & Murphy, PLLC, and served with Ed Kneedler in the office of the Solicitor General from 2001-2008.

Posted in Tributes to Ed Kneedler