Empirical SCOTUS: The wide arc of the Supreme Court

on Oct 3, 2018 at 3:50 pm

The Supreme Court now hears around 70 arguments a term, and each case tends to have issues unique from others on the court’s docket. After the court’s merits docket is assembled each term, however, similarities between cases become apparent and these similarities may present an area of law in which the court is more invested and wants greater resolution. Such areas can be either broad-based or narrow.

Last term the court settled multiple issues surrounding the First Amendment. The court resolved public-sector employees’ First Amendment rights regarding agency fees in Janus v. AFSCME, First Amendment retaliatory-arrest claims in Lozman v. Riviera Beach, acceptable political apparel at polling places in Mansky v. Minnesota Voters Alliance, and the compatibility of the California Reproductive Freedom, Accountability, Comprehensive Care, and Transparency Act with the First Amendment in NIFLA v. Becerra. It also worked through the free exercise First Amendment question in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, while it left the free speech component of the case unanswered.

During the 2016 term, the court resolved several issues relating to patent law in the cases Samsung v. Apple, SCA Hygiene v. First Quality Baby Products, Life Technologies v. Promega, Sandoz v. Amgen, Impressions Products v. Lexmark and TC Heartland v. Kraft Foods Group Brands. Although there was a drop off in such cases for the 2017 term, the court heard several salient patent cases last term as well, with Oil States Energy Services v. Greene’s Energy Group, SAS Institute v. Iancu and WesternGeco v. ION Geophysical Corp.

What will the court hear this term? According to Professor Rory Little, the court’s merits docket is currently filled with criminal law cases. That is not all though. Although the court’s argument calendar currently lacks blockbuster cases, certain patterns are evident in the types of cases the court has already accepted for oral argument.

One of the most interesting ways to locate underlying patterns without significant prior information about content is through unsupervised learning and more specifically through topic modeling. Empirically minded legal academics have used topic models to gauge issues before the court in the past. In a recent paper, Professors Michael Livermore, Dan Rockmore and Allen Riddel used topic models to longitudinally study agenda formation in the Supreme Court. Professor Douglas Rice used topic models in an article looking at differences in framing between Supreme Court majority and dissenting opinions. In another article, Professors Benjamin Lauderdale and Tom Clark used topic models along with other methodological tools to highlight issues in Supreme Court cases along with the justices’ preferences based on case issues. This post takes a cut at the court’s recent cases to see what the justices have examined in the past several terms as well as what they will review this term.

This is an interesting and dramatic time for the Supreme Court. Although expectations ran high for a conservative agenda this term based upon Justice Anthony Kennedy’s departure, now the reality is setting in that the court might consist of eight justices for at least the near future and so the conservative agenda might be shelved, if only temporarily. The public expects the court to handle cases with significant impacts in the near future, although the majority of the public’s position is not always aligned with that of the majority of the justices. The uncertainty about the ninth seat on the court seems in any case to have left the court without cases dealing with hot-button issues like abortion or voting rights.

Although one of the key aspects surrounding topic models is that they don’t require much prior substantive knowledge of the area under exploration, one setting that users input is the number of issues that the algorithm will uncover. This number could be arbitrary but is usually either based on some expectation or can be narrowed through a process of iterating the algorithm several times with different parameters for the number of topics.

2013-2017

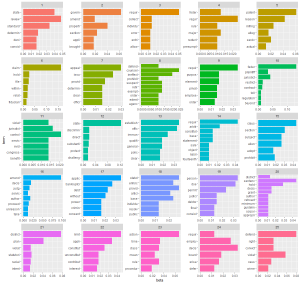

The texts I used to generate the topics were each case’s question or questions for the court as contained on the Supreme Court’s website (as in this example from last year’s case Jennings v. Rodriguez). Although the estimate of topics is rough at best, I set the number of issues for cases between 2013 and 2017 to 25 and the number of words per topic to six (although sometimes the number of words is greater than six if there are equally weighted words). The words in the topics were stemmed so that words with the same root were combined (for example, tell, tells and telling would be grouped together). The topics were derived as follows:

When evaluating topics, notice that the beta values or relative level of significance below each topic are on different scales. A larger number in these scales indicates a greater importance of a term to a topic and consequently the presumed importance of the term to cases that fall within that topic.

Some of the topics can clearly be associated with case categories. Topic 5, for instance, focuses on patent cases, Topic 13 on qualified immunity, Topic 17 on bankruptcy, and Topic 20 on criminal sentences. The cohesion between terms in other topics is vaguer. Topic 22, for example, likely deals with campaign contributions and Topic 21 with statutes that have differential race-based effects. Topic 1 might relate to the review of state statutes but also might be more in line with rules of federalism. Topic 9 likely has some relationship to employment discrimination, although this is still not entirely clear based on the words alone.

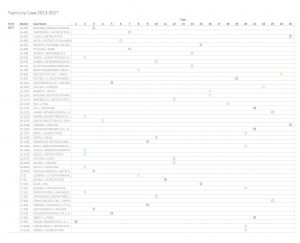

We can get a better sense of the connective glue between terms in a topic by matching cases with their top topics (Cases are weighted into multiple topics, but for the purpose of this analysis only the top-ranked topic per case was retained.). This also allows us to differentiate cases by their underlying issues as well as to group similar cases together. The next figure is an exhaustive list of 320 argued cases between the 2013 and 2017 terms along with each case’s top issue.

With topics and cases in hand, we can begin the process of matching cases to topics and interpreting how and why cases fit into their respective topics.

An example from each of the court’s terms between 2013 and 2017 will help illustrate this interpretive technique. During the October 2013 term, the court decided McCullen v. Coakley, which dealt with abortion-protester buffer zones. The case’s top topic was 18, with the word stems: statut, enforc, provid, articl, base, individu, resolv and public. Although the link between these terms and abortion clinics may not have been clear at the outset, more clarity is attained with a little information about this case (even the modicum provided above) as it relates to this topic.

In the October 2014 term, the court heard the employment discrimination case Young v. United Parcel Service. The case specifically looked at disparate treatment of pregnant women, of whom some but not others were afforded accommodations. This case fell under Topic 7, with the term stems: appeal, issu, provid, determin, clear and offici. These stems do not clearly indicate that they relate to employment discrimination on their face, but when connected to this case the relationship becomes evident.

The court heard the standing case Spokeo v. Robins during its October 2015 term. Spokeo fell under Topic 9. Topic 9 looks at requirements and elements that both fit well with questions of standing. Spokeo also looked at the enforcement of rights between private parties. Based on the topic terms, Spokeo is properly categorized under Topic 9.

During the October 2016 term, the court heard the criminal-sentencing case Beckles v. U.S. Beckles’ main topic is number 20, which among other things includes sentences, decisions, retroactivity, guidelines and minimum. These are all very important words in relationship to Beckles, which specifically dealt with the Federal Sentencing Guidelines.

Last term the court heard Gill v. Whitford. Although the substantive questions in the case remained largely untouched, this gerrymandering case, which fell under Topic 21, dealt with election districts, voting plans and violations of the First and 14th Amendments.

Cases are not isolated to one topic, and topics do not always clearly establish the main issues in cases. Take last term’s case Carpenter v. U.S. Carpenter’s main topic is 7. Carpenter dealt with Fourth Amendment protections against warrantless searches of cell-tower records. Topic 7 does not overtly describe these facets with its terms. Carpenter most likely falls into a mix of several topics with no topic in particular dominating its composition. Based on this analysis, not all case issues are going to be clarified by the main topics, although some cases will be described much better than others.

2018

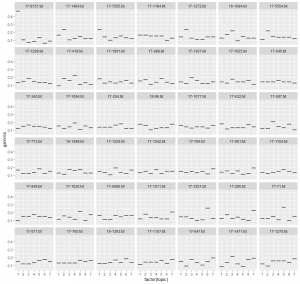

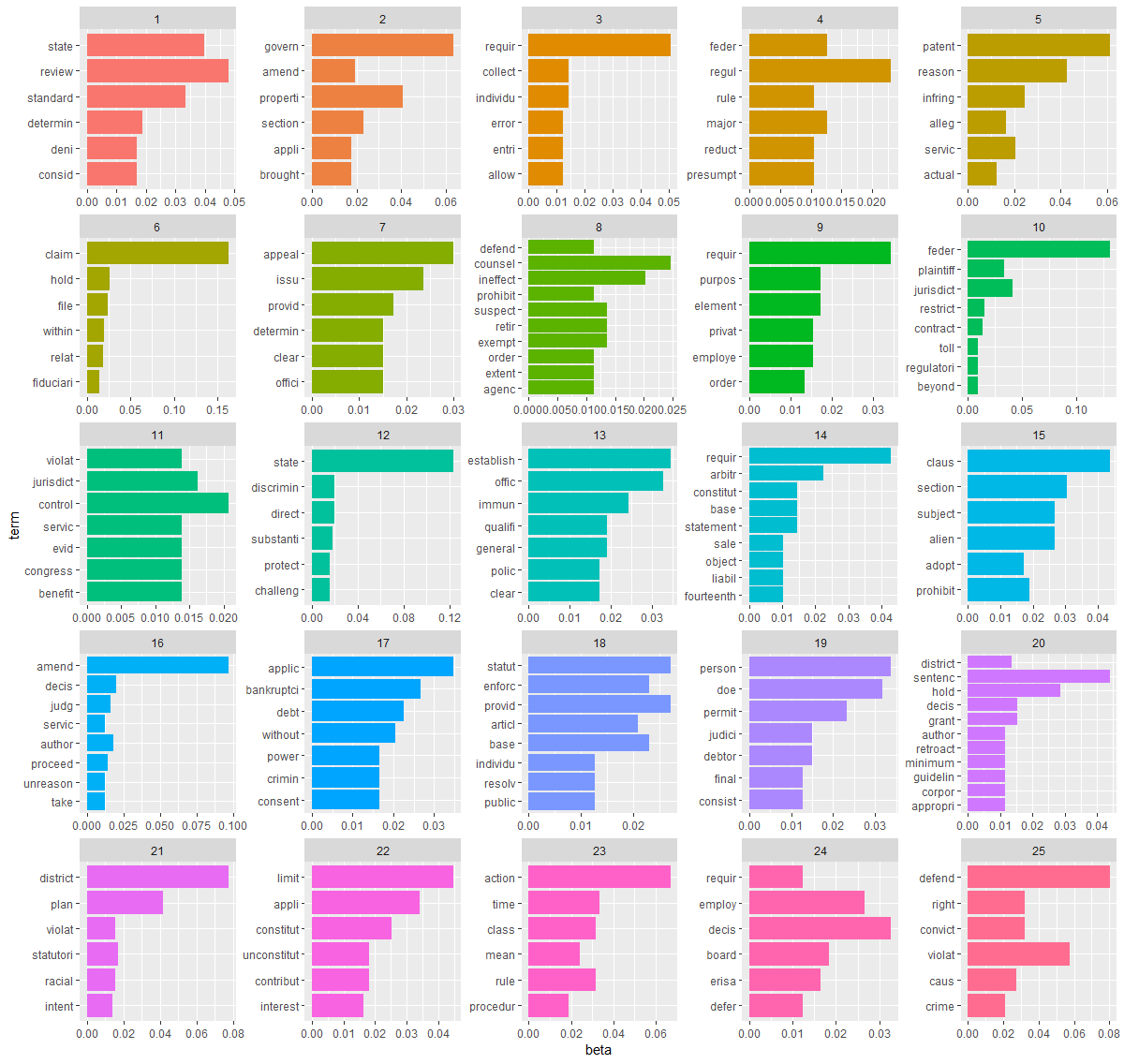

For the October 2018 term I examined the questions presented in 42 petitions related to arguments that the court will or already did hear. Because this sample is more limited than the larger sample of cases between the 2013 and 2017 terms, I limited the number of topics to seven, with seven terms per topic (unless multiple terms had equal weights).

Topic 1 clearly deals with capital punishment and Topic 2 relates to arbitration agreements. The cohesion between words in other topics is either less clear or includes a mix of issues. The cases that fall under certain topics may also provide the connective glue between words in the topic.

Because the number of cases for the October 2018 term was more manageable with 42, I included the relative weights of each topic for each case as is displayed below.

Some cases bear strong relationships to one topic, while others relate to multiple topics. We see that Bucklew v. Precythe and Madison v. Alabama, both death penalty cases, have Topic 1 as their main topics, but Bucklew has a greater relationship to Topic 1 than does Madison.

Azar v. Allina Health Services looks at whether the Department of Health and Human Services is required to follow certain procedures before providing challenged instructions to Medicare contractors. The case is predominantly under Topic 2, which looks at employers and requirements, but doesn’t examine other terms under the topic like design and immunity. Stokeling v. U.S., a criminal case, also falls mainly under Topic 2. This case looks at requirements and elements of “violent felonies” but has little to do with other aspects of the topic, like design and arbitration.

Weyerhaeuser Company v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which was recently argued before the court, is mainly under Topic 5. This topic covers many of the essential aspects of the question in this case like critical, habitats and land, although several of the other words like author, instruct and career are unrelated to the case’s question.

Not all cases are classified equally well by these topics and some cases are better categorized by multiple topics rather than by just one. Looking at the different sets of topics we can get a sense of the cases the court heard or will hear based on words related to the cases’ main questions. We can also look at the sets of topics to give a sense of the terrain of cases before the court. Several of the topics for the 2018 term have words related to criminal law. Others focus on arbitration and employment, which is another of the court’s focal points early in this term. Other, less apparent aspects of this term’s cases are also brought to light with these topics. Topic 3, for example, focuses on foreign, nation and states, all which are components of the questions in Jam v. International Finance Corp. and Republic of Sudan v. Harrison.

This method for examining case issues will not perfectly locate all issues before the court. It will, however, provide a good summary of important issues and especially of ways to bracket multiple cases under similar topics. It may also illuminate new ways of categorizing cases that were previously undetected through qualitative analysis alone.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.