How academic briefs shape Supreme Court decisions

Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, overturning the court’s recognition of a constitutional right to an abortion. To justify their opinions in Dobbs, the justices cited six different briefs submitted by scholars. This intense marshaling of academic expertise exemplifies a broader transformation in Supreme Court practice: Justices increasingly turn to such briefs not merely for doctrinal support but for historical practices, empirical claims, and constitutional analysis.

Scholars’ briefs occupy a distinct space. Unlike party briefs, which advance partisan positions, such briefs purport to offer disinterested expertise with academic authority that practicing attorneys cannot replicate. But their expanding influence raises questions about whether these briefs genuinely inform constitutional interpretation or merely provide scholarly backing for predetermined conclusions.

This article examines an original dataset of 103 scholar briefs and over 2,300 individual scholars cited by the Supreme Court between the 2015-16 and 2024-25 terms to map the landscape of academic influence on contemporary Supreme Court decision-making and to examine what briefs matter most to the justices.

The cases that draw scholars

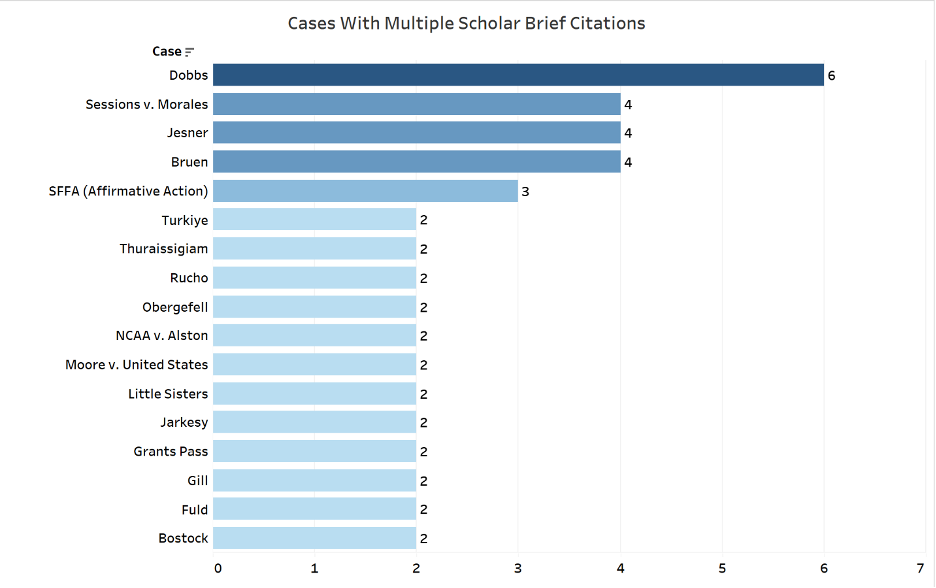

Let’s start with the cases themselves. The distribution of such briefs’ citations across cases is remarkably uneven. Dobbs stands as an extraordinary outlier with six cited briefs. Three cases – Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (on affirmative action in college), Jesner v. Arab Bank (on corporate liability), and New York State Pistol & Rifle Association v. Bruen (on the right to carry under the Second Amendment) – each drew four cited briefs. Below this, numerous cases cite two scholar briefs each, spanning diverse doctrinal areas from habeas corpus to intellectual property.

This suggests that the citation of such briefs remains the exception rather than the rule, although scholars’ briefs are being cited with increasing prominence, especially in major civil liberties matters which tend to also be the court’s most publicized cases.

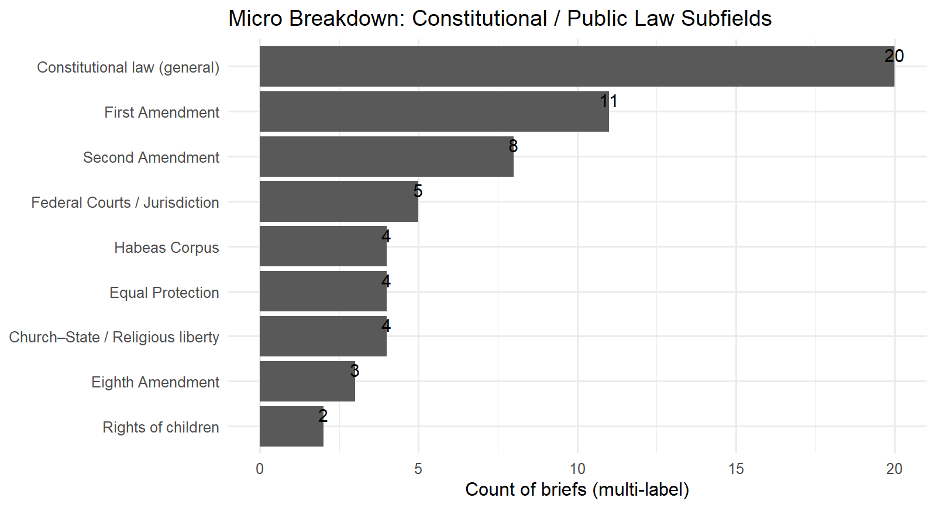

As for subject matter, Constitutional law (unsurprisingly) emerges as the dominant category, with twenty briefs – nearly one-fifth of all citations. Within constitutional law, general constitutional questions account for twenty briefs, First Amendment issues for eleven briefs, Second Amendment questions for eight briefs, and federal jurisdiction, habeas corpus, the equal protection clause, and the establishment clause each generated four cited briefs. The clustering around the First and Second Amendments suggests ongoing doctrinal development where originalist and living constitutionalist approaches clash, making academic work particularly valuable there.

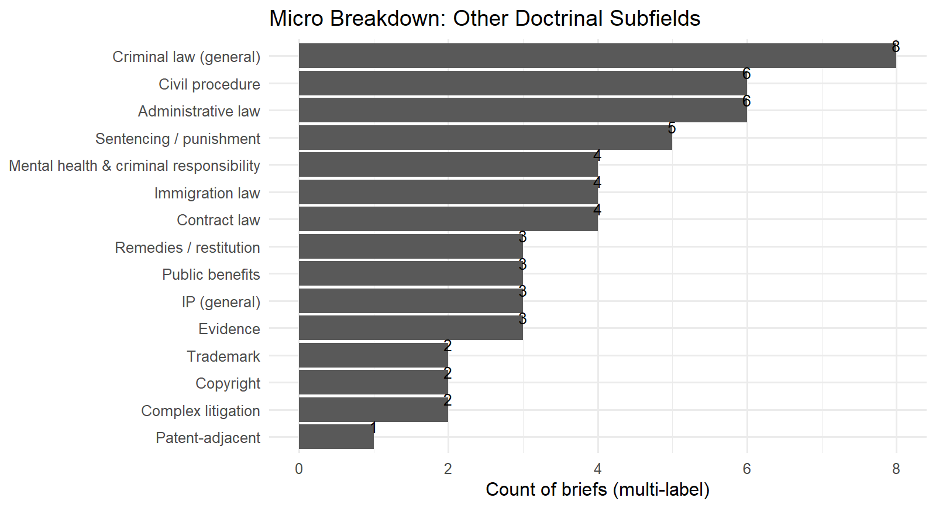

Beyond constitutional law, criminal law leads the non-constitutional fields with eight briefs, followed closely by civil procedure and administrative law (six briefs each). Sentencing and punishment issues generated five cited briefs.

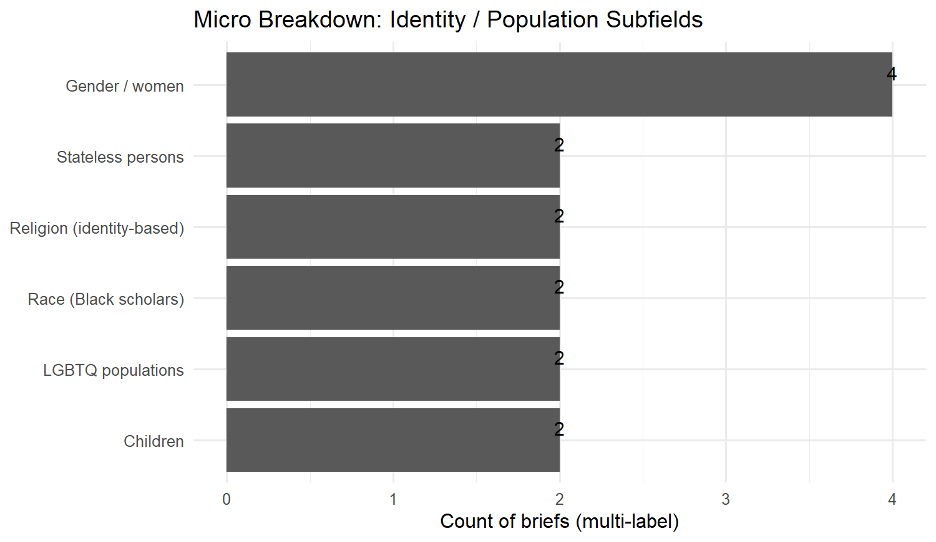

A notable subset addresses identity-based legal issues and the rights of specific populations. Here, gender and women’s issues had four cited briefs. Stateless persons, religion as identity, race (specifically Black scholars’ perspectives), LGBTQ populations, and children’s rights each garnered two cited briefs. These relatively small numbers – compared to general constitutional law briefs – suggests that identity-based expertise remains supplemental rather than central to judicial reasoning.

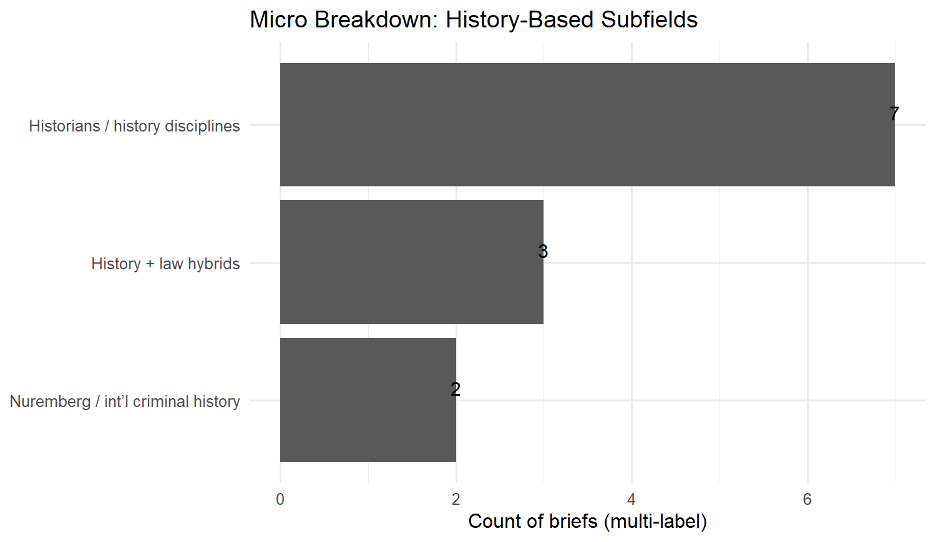

Historical expertise has also come to play an increasingly prominent role. Seven cited briefs came from historians or history-related disciplines, with three briefs combining historical and legal analysis. This reflects the court’s contemporary emphasis on original public meaning and historical tradition in cases like Bruen, which articulated a “history and tradition” test, and Dobbs, which grounded its analysis in 19th-century abortion statutes. Historical scholarship now directly shapes constitutional doctrine.

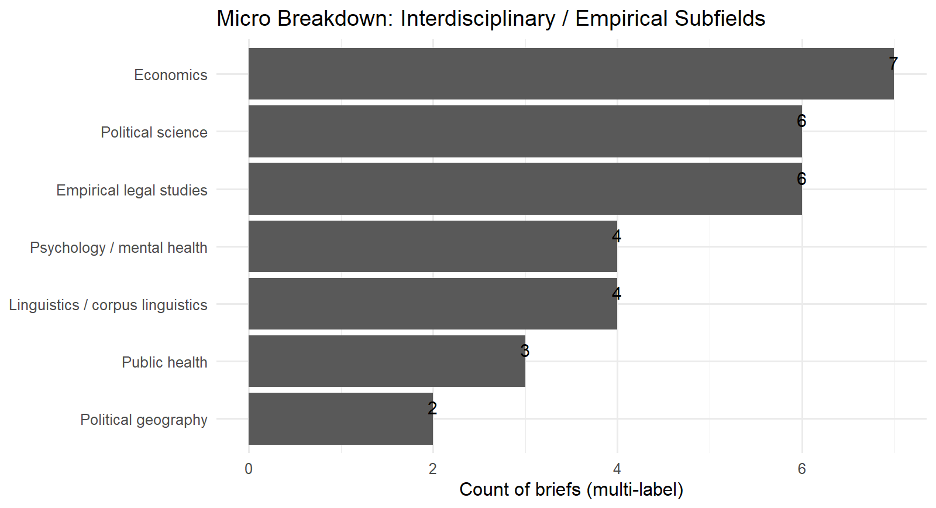

Finally, the court increasingly cites briefs containing empirical and interdisciplinary perspectives.

Here, the field of economics leads decisively with seven cited briefs, followed by political science and empirical legal studies (six briefs each), psychology/mental health (four briefs), linguistics and corpus linguistics (four briefs), and public health (three citations). The presence of corpus linguistics briefs – using large text databases to determine words’ meanings – demonstrates the court’s willingness to embrace novel methodologies for interpretation. And the usage of such briefs is only likely to intensify given the current court’s turn towards textualism.

The geography of elite legal academia

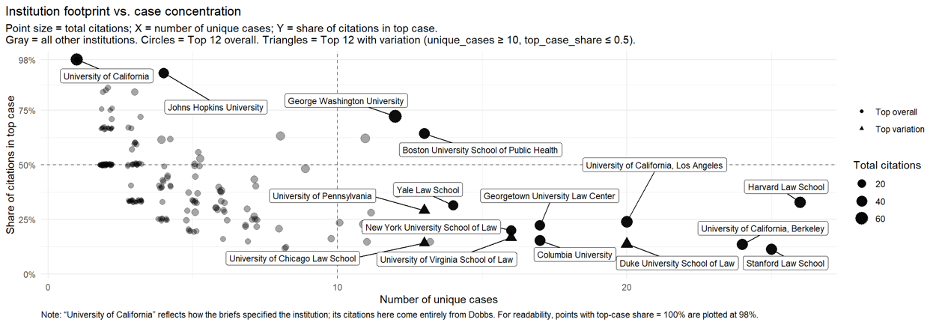

Another aspect worth considering is what schools are generating the most scholarship cited by the court.

As charted above, Harvard Law Schools’ scholarship is cited in multiple briefs across different disputes. Stanford Law School, Berkeley, UCLA, Duke University School of Law, Columbia, Georgetown University Law Center, NYU School of Law, University of Chicago Law School, Penn, and University of Virginia School of Law likewise generated repeated citations across different doctrinal contexts. And while the concentration of elite institutions is significant, the presence of hundreds of schools suggests meaningful participation beyond the top-ranked ones.

The most influential scholars

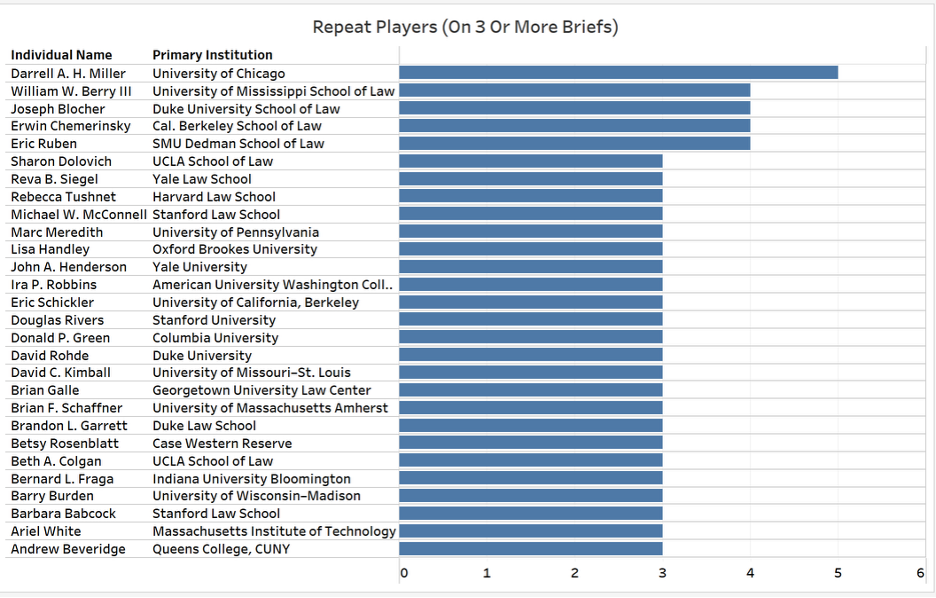

Individual scholars also vary dramatically in brief citation frequency. Twenty-eight scholars appeared as signatories on three or more cited briefs:

The top cited scholar, with five briefs, was Darrell A. H. Miller from Duke Law, who concentrated mainly on the Second Amendment. Two professors filed in four cited briefs: William W. Berry III (University of Mississippi School of Law) in criminal law, and Joseph Blocher (Duke Law), also mainly in Second Amendment cases.

Many frequently cited scholars hold appointments at elite institutions, although several prominent entries hale from lower tiered schools.

Some of these scholars specialize in particular constitutional domains (the Second Amendment, federalism), while others contribute across multiple fields. Combined JD/PhD credentials also appear frequently among top scholars, suggesting that interdisciplinary training enhances one’s influence. And most of these scholars are senior, reflecting both accumulated expertise and established professional networks facilitating brief coordination.

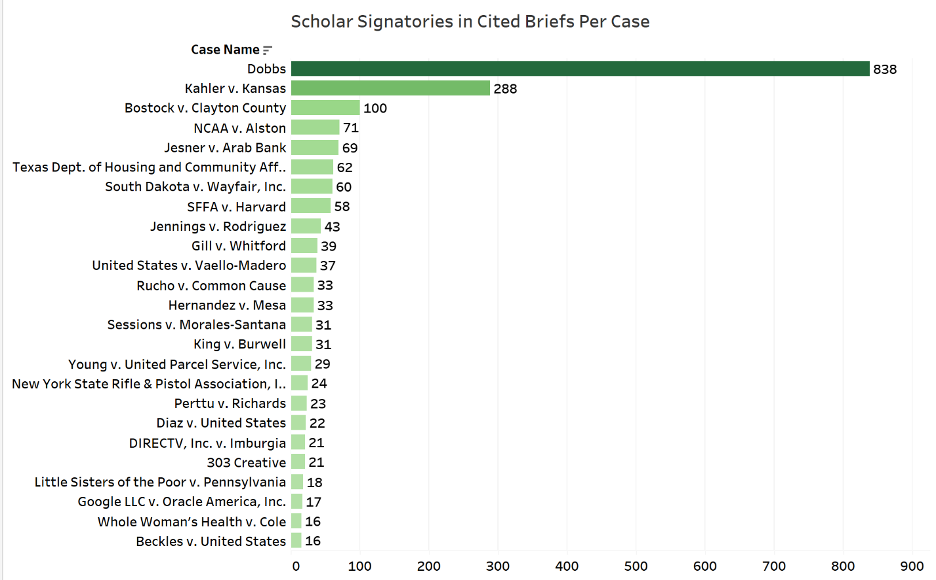

The number of scholars signing each cited brief further varies dramatically:

Dobbs stands far above all other cases with 838 total scholar signatories across its cited briefs – an extraordinary mobilization of academic opinion. Kahler v. Kansas, which involved the insanity defense, drew 288 signatories, while Bostock v. Clayton County, the landmark LGBTQ employment discrimination case, garnered 100 signatures.

Implications and open questions

So what does this tell us about legal academia and the court? First of all, the data reveal a court increasingly comfortable turning to academic expertise across a diverse range of fields, with particular reliance on constitutional and criminal law. Second, as for the briefs themselves, elite law schools dominate, with a small group of institutions and scholars appearing repeatedly. Finally, the justices show a willingness to engage with historical scholarship and empirical evidence – when the cases demand it.

Of course, these patterns raise questions about actual influence versus mere citation. Justices may cite scholars’ briefs not because they changed any minds, but because they provide authoritative support for conclusions already reached. In particular, the concentration at elite institutions with established Supreme Court networks raises questions about whether cited briefs represent genuine scholarly consensus or carefully curated perspectives aligned with the litigants’ interests. The answer likely varies by case, justice, and expertise type – but where exactly the justices are getting their information from provides an important start.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS, Featured, Recurring Columns

Cases: Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization