The case that turned the justices into art critics

In Dissent is a recurring series by Anastasia Boden on Supreme Court dissents that have shaped (or reshaped) our country.

I. The artist formerly known as Prince

It was 1981, and Prince was not yet Prince. He was Prince Rogers Nelson, an “up and coming” 22-year-old artist, whom Lynn Goldsmith persuaded Newsweek to allow her to photograph. Prince may have been a newcomer, but Goldsmith was not. She was a respected rock-and-roll photographer known for her intimate portraits of rockstars, including Van Halen, James Brown, and Mick Jagger. In Prince she saw someone still figuring out who he was before the world decided that he was a star. She sat him in front of a simple white backdrop. Nothing grand. His eyes dark, steady, but vulnerable.

What resulted was a portrait of a man with power not yet claimed. Goldsmith’s studio photos of Prince didn’t end up running in Newsweek, but she held onto them – and her copyright.

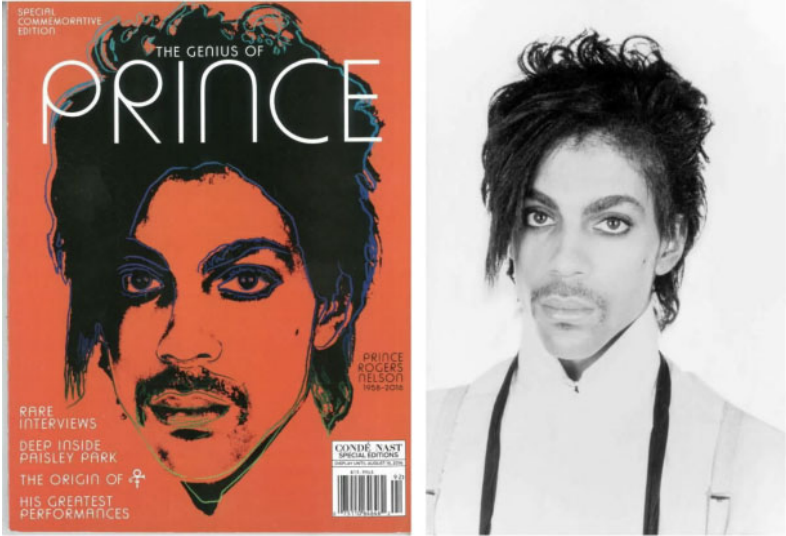

Three years later, another artist would see in that same face something entirely different. Andy Warhol would Warhol-ize Goldsmith’s photo and produce an image of Prince as a music icon. Decades later, these two contrasting portraits of Prince would wind up at the Supreme Court, with Goldsmith claiming copyright infringement and Warhol’s foundation claiming “fair use.” The parties called on the justices to decide whether Warhol had sufficiently transformed Goldsmith’s photo to avoid copyright infringement.

A seven-justice majority said he had not. In dissent, Justice Elena Kagan used paintings, music, and literature to school the majority on art history – and the very nature of judging.

II. The silkscreen

Three years after Goldsmith photographed young Prince, Vanity Fair called. The magazine was running a profile on the artist, now ascendant after his album “1999.” The magazine paid Goldsmith $400 for a one-time license of her photo as an “artist’s reference.” They gave the portrait to Warhol, who flattened the shadows, used a silkscreen to carve the jawline into hard angles, and drenched the face in a pop of bright purple. He was not trying to capture a person; he was illustrating Prince as an icon. While Goldsmith had captured Prince while he was still rising, Vanity Fair’s piece, by contrast, was titled, “Purple Fame: An Appreciation of Prince at the Height of His Powers.” The magazine printed Warhol’s silkscreen and credited Goldsmith for the original photograph in small text.

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol hadn’t stopped with one image. He had made over a dozen silkscreen prints and kept them in his private collection. In addition to a purple Prince, there was an orange Prince and a blue Prince. There were 14 silkscreens and two pencil drawings in all. Warhol once said, “The more you look at the same exact thing, the more the meaning goes away, and the better and emptier you feel.” In that vein, he had repeated Prince’s flattened image in several colors, showing a man whose humanity becomes harder to access as he becomes more famous.

Decades passed, with Prince selling over 150 million records worldwide and reinventing himself along the way, all while staying notoriously protective of his image. He released 39 studio albums, including “Sign o’ the Times,” “Purple Rain,” and “The Slaughterhouse” (no relation to Justice Stephen Field’s masterful dissent in The Slaughter-house Cases). He set several records, including being the first artist to simultaneously have a number one film, album, and single in the U.S. In 1993, he adopted an unpronounceable symbol as his name to protest what he saw as his label’s copyright of his very identity. In 2000, he reclaimed his old moniker. He notoriously hated compulsory licensing laws, which allowed other artists to cover his songs without his permission, and repeatedly refused Weird Al’s requests to parody his work. In 2010, Prince even fought to remove a mother’s video from YouTube that depicted her baby dancing to “Let’s Go Crazy,” eventually resulting in a ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit.

In 2016, he died.

That same year, Vanity Fair’s parent company Condé Nast sought to use Warhol’s image once again for a tribute cover. But this time, they discovered Warhol’s trove of other Prince images. And rather than reprinting Purple Prince, they chose to run Orange Prince, paying Warhol’s foundation $10,000 for it. Goldsmith picked up the magazine and recognized the vulnerable face she had photographed staring back at her – printed without her permission. She called the foundation and notified them that she believed they had infringed her copyright. The foundation then sued Goldsmith, seeking a declaratory judgment that Warhol’s use of her photo wasn’t infringement, or, alternatively, that it was “fair use.”

III. The legal frame

Fair use is a statutory defense to copyright infringement claims premised on the idea that, without room to remix, innovation will freeze. In a case in 1994 involving 2 Live Crew’s parody of Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman,” the Supreme Court drew on Justice Joseph story when ruling that the “central purpose” of the fair use investigation is to determine whether the new work “adds something new,” “altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” “[I]n other words,” it asks “whether and to what extent the new work is ‘transformative.’” If the second piece is deemed transformative, it’s then considered a fair use of the original.

Even though both the parody and the original piece in that case were used for commercial purposes (to sell music), the court ruled that 2 Live Crew’s lyrics (“Big hairy woman you need to shave that stuff/Big hairy woman you know I bet it’s tough”) transformed the original into something different altogether.

Courts consider four factors under the “fair use” test, but only the first factor – the “purpose and character” of the new work – was at issue in Goldsmith’s case. The district court had ruled that the factor weighed in Warhol’s favor because he had transformed the original work’s style and meaning. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit reversed, ruling that adding new expression wasn’t enough. What mattered more, according to the 2nd Circuit, was that both pieces depicted a musical artist for commercial purposes in a magazine. At the Supreme Court, Warhol’s foundation argued the 2nd Circuit’s analysis was wrong because courts should not only consider the overall purpose of the art, but the meaning of the art, too.

Seven justices disagreed and sided with Goldsmith. Writing for the majority, Justice Sonia Sotomayor paid little attention to the works’ different meanings and minimized Warhol’s stylistic changes. The first fair use factor focuses on a work’s high-level purpose and whether it is commercial or non-commercial, she said, and both Goldsmith’s photograph and Warhol’s image were used for the commercial purpose of illustrating a magazine story about Prince.

Sotomayor stressed – and Justice Neil Gorsuch emphasized in a concurring opinion – that the court’s opinion was narrow; it did not ban Warhol’s art from museums, exhibitions, or scholarly use. Just as Warhol’s prints of Campbell’s soup cans were fair use because they were not used to advertise soup, so too might the foundation claim fair use when using his Prince pieces for non-commercial purposes. But here, Warhol’s intended meaning could not override Goldsmith’s right to market her photo to magazines. Sotomayor concluded, “Copying might have been helpful to convey a new meaning or message. It often is. But that does not suffice under the first factor.”

IV. Nothing compares 2 the dissent

Kagan’s dissent, joined only by Chief Justice John Roberts, is not a typical dissent. It reads like she had walked into a museum, stood the justices in front of two images, asked them to see the difference, and grew tired of waiting. While Sotomayor’s opinion had been sympathetic to Goldsmith, touting her pioneering experience as a woman and her many accolades – and subtly shading Condé Nast’s failure to pay her – Kagan showed great admiration for Warhol.

The majority, she said, lacked “appreciation” for what Warhol did with the photograph. It was not a “modest alteration[],” but an extreme transformation. She painstakingly dissected Warhol’s works, demonstrating what made him (in her view) the “avatar of transformative copying.” By way of example, Kagan reproduced his famous Marilyn Monroe print as well as the original photo it was based on, explaining (in line with an expert who had testified at trial in the district court) how he had cropped her head to create a “disembodied” being “magically suspended in space,” and filled it with “unnatural, lurid hues.” “It does not take an art expert to see a transformation,” she wrote, “but in any event, all those offering testimony in this case agreed there was one.” Suppose you were the editor of Condé Nast and you were asked to choose between Goldsmith’s photo and Warhol’s print, “Would you say that you don’t really care,” she asked, or agree to “flip a coin?” Apparently seven justices thought yes. “All I can say is that it’s a good thing the majority isn’t in the magazine business.”

“Worse” than not noticing the differences between the original photo and Warhol’s print, the majority “d[id] not care” about them. This “doctrinal shift” from focusing on an artist’s expression to their overall (commercial) ends, Kagan said, “ill serves copyright’s core purpose,” “hampers creative progress,” and “undermines creative freedom.”

In Kagan’s view, Warhol’s creative transformation should matter because copyright exists not just to encourage creators to make their art publicly available, but to inspire people to build on it. “Nothing comes from nothing, nothing ever could,” she said, borrowing a quote from the songwriter Richard Rogers. She repeated this sentiment several times throughout her opinion, quoting Mark Twain, Mary Shelley, and other artists, who all said the same thing but in different words. Stravinsky apparently said it most bluntly: “great composers do not imitate, but instead steal.”

Shakespeare was a serial borrower, Kagan pointed out. “Lolita,” too, was a borrowed story. And Robert Louis Stevenson confessed to borrowing from Edgar Allen Poe and Washington Irving when writing “Treasure Island.” Kagan reproduced three separate paintings spanning different generations to show how a portrait of Venus had influenced Titian, which had influenced Manet. Here, the Supreme Court should have borrowed from its own precedent, she said, which had always considered the artists’ expressiveness under the first factor. Instead, the majority had focused solely on whether both artists were making money, which she believed would ultimately “ma[ke] our world poorer.”

In a footnote in the majority opinion, Justice Sotomayor responded that this line (and others) were a “series of misstatements and exaggerations.” In a footnote in the dissent, Justice Kagan shot back that the majority’s hyper-focus on her opinion was self-refuting, “[a]fter all, a dissent with ‘no theory’ and ‘[n]o reason’ is not one usually thought to merit pages of commentary and fistfuls of comeback footnotes.” She urged readers to read the relevant Supreme Court opinions for themselves and to consider the majority’s “ratio of reasoning to ipse dixit. With those two recommendations, I’ll take my chances on readers’ good judgment.”

Kagan’s opinion, full of art references and reproductions and something of a miniature masterpiece itself, shows a willingness to engage in a way seven justices would not. Whereas the majority read the statute narrowly to avoid weighing artistic meaning – reducing the inquiry to formal categories like commercial or non-commercial – Kagan insisted that courts cannot answer the question of fair use without grappling with the work itself. In her view, reading the statute’s text devoid of its purpose, and perhaps out of discomfort with the idea of judges judging art, was itself judicial overreach. And while the majority might have thought that allowing meaning as an escape hatch to copyright liability might allow too much borrowing, Kagan thought that reducing “fair use” to whether two artists had the same general purpose would allow too little.

This narrative isn’t cleanly ideological. Sotomayor and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson joined an opinion associated with restraint, while the chief – who famously said that the job of a judge is to merely “call balls and strikes” – joined a dissent urging deeper judicial engagement. And Kagan and Justice Clarence Thomas, two of the most consistent defenders of free speech, found themselves on opposite sides. The split, then, cannot be easily explained in terms that people usually use to divide the court. The case forced the justices into a role they openly dislike: becoming arbiters of aesthetic meaning. But two justices thought the law required it, and seven ruled that it did not. The result was a decision equally about art as about judging – and a reminder that the hardest cases require judges to judge even when they would rather look away.

Posted in In Dissent, Recurring Columns

Cases: Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith