A justice’s most lasting legacy

Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

Among a president’s most enduring legacies are the federal judges they appoint – particularly Supreme Court justices. This permanence stems from life tenure, a constitutional provision that ensures judicial independence but also transforms each appointment into a generational bet on the nation’s legal future.

Yet history is littered with presidential miscalculations. President Dwight D. Eisenhower supposedly called his appointment of Earl Warren as chief justice one of his “biggest mistakes,” as Warren became a liberal stalwart for over a decade. Justices John Paul Stevens and David Souter, both nominated by Republican presidents, evolved into some of the court’s most liberal members. Had Republican presidents consistently installed reliably conservative justices since the mid-20th century, the court would have been far more conservative than it actually was (and perhaps even is today).

But presidential legacy is only part of the story. The judges themselves have developed their own succession strategies. In recent years, a striking pattern has emerged: Supreme Court justices now appear ready to retire only with tacit – or perhaps explicit – assurances that they will be replaced by someone they helped shape, typically a former clerk. This, combined with the fact that so many such clerks now serve as judges on the lower courts, has had profound effects – and will continue to do so – on the federal judiciary.

Judicial successors

Supreme Court clerkships represent a relatively modern phenomenon, emerging primarily as the court evolved through the 20th century. The number of clerks allocated to each justice has steadily increased, from two until 1969, to three in the 1970s, and to four in 1980. This has also expanded the pool of potential judicial heirs. Justice Byron White was the first justice to have clerked for a former justice – Chief Justice Fred Vinson in his case. Chief Justice William Rehnquist clerked for Robert Jackson, and Stevens for Wiley Rutledge. Stevens was confirmed in 1975. Of the next several justices – Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy, Souter, Clarence Thomas, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg – none held a Supreme Court clerkship.

Then came Justice Stephen Breyer, confirmed in 1994, who had clerked for Justice Arthur Goldberg. The majority of justices appointed after 1994 held Supreme Court clerkships at one point in their careers – Chief Justice John Roberts for Rehnquist, Elena Kagan for Thurgood Marshall, Neil Gorsuch for Kennedy (although he was originally hired by White before his retirement), Brett Kavanaugh for Kennedy, Amy Coney Barrett for Scalia, and Ketanji Brown Jackson for Breyer. Neither Samuel Alito nor Sonia Sotomayor clerked at the Supreme Court level, leaving them a minority in this regard.

Indeed, since Kennedy retired in 2018, the phenomenon of justices being replaced by their clerks has become the norm rather than the exception. As noted, not one but two of Kennedy’s former clerks were appointed by President Donald Trump in succession: Gorsuch filled Scalia’s seat, which had remained vacant longer than any in court history, and Kennedy’s own seat went to Kavanaugh. According to Politico, Kennedy’s backroom conversations with Trump prior to his departure may have been used to facilitate a transition. For Trump, this was advantageous: he could install more consistently conservative justices than Kennedy, who had occasionally sided with liberals on consequential civil liberties cases like the same-sex marriage decision in Obergefell v. Hodges.

This trend of former clerks joining the court continued with Barrett, a Scalia clerk, replacing Ginsburg after her death, and Jackson, a Breyer clerk, succeeding her former mentor.

The downstream effects of Supreme Court clerkships can reshape American law across generations. Consider the lineage from Jackson to Rehnquist, who clerked for Jackson, to Roberts, who clerked for Rehnquist. And this chain of influence now spans more than half a century, with each generation of jurists passing their interpretive methods to the next.

Breaking down the numbers

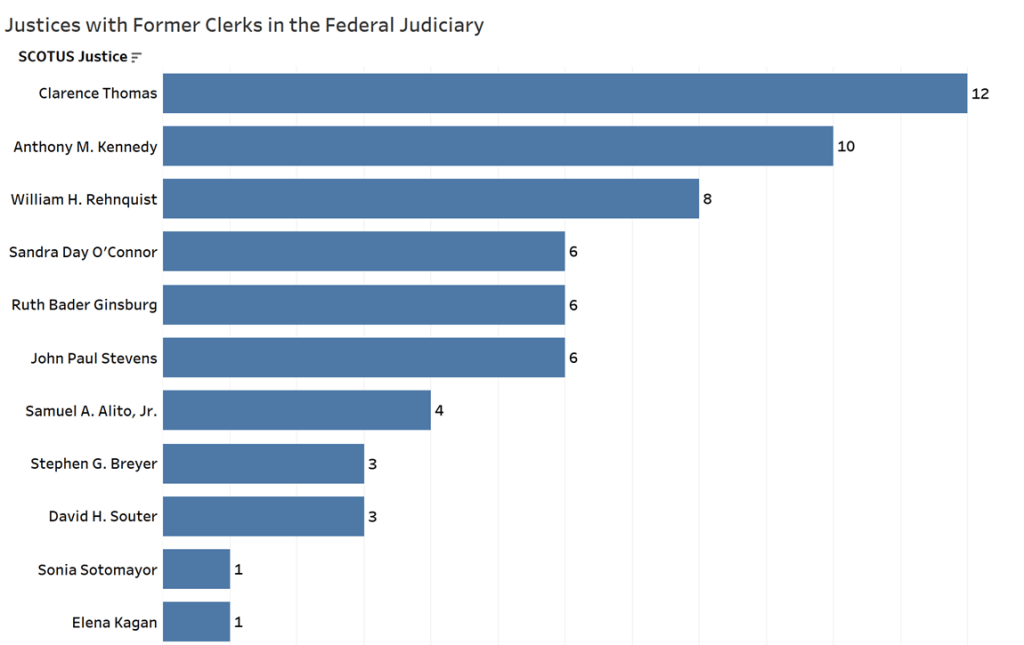

But that is not the full picture. The data also reveals how widespread former Supreme Court clerks are in the federal judiciary as a whole.

Thomas leads by a substantial margin, with 12 former clerks hired as federal judges – a testament both to his long tenure and his deliberate cultivation of conservative judicial talent. Kennedy follows with 10 clerk-judges, including the two Supreme Court justices mentioned earlier. Rehnquist placed eight former clerks, continuing his influence even after his 2005 death.

Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Ginsburg each count six former clerks in the federal judiciary, and Stevens also placed six. Alito has four clerk-judges, while Breyer and Souter each have three. (Perhaps most surprisingly, given his position as chief justice, Roberts has not yet seen a former clerk become a federal judge.)

Implications: the self-replicating judiciary

These patterns of clerk placement, both on the federal judiciary and the Supreme Court itself, point toward a fundamental transformation in how the federal judiciary perpetuates itself. What began as perhaps an informal preference for continuity has evolved into something approaching a self-replicating system, where judicial philosophies pass from one generation to the next through carefully cultivated mentor-clerk relationships. And the implications extend far beyond individual careers or even the ideological balance of particular courts.

First, the clerk pipeline is creating unprecedented ideological coherence within judicial camps. When Scalia’s originalism passes to Barrett, for example, we see not just individual judges but schools of thought reproducing themselves and evolving across levels of the federal judiciary.

Second, the emphasis on clerk credentials may be narrowing the diversity of judicial backgrounds and experiences. When Supreme Court seats increasingly go to former clerks of previous justices, and circuit judgeships follow similar patterns, the federal judiciary risks becoming a closed system that prizes insider credentials over other forms of distinction.

Third, strategic retirement is likely to become even more entrenched as justices and judges see their former clerks successfully ascend to higher courts. Why risk having your seat filled by someone who will dismantle your life’s work when you can time your retirement to ensure a former clerk succeeds you? This calculus transforms judicial service from a commitment to decide cases until incapacity into a more strategic career-management decision. The court becomes less independent of politics, not more, as retirements increasingly align with electoral cycles.

Finally, the concentration visible in these numbers – particularly Thomas’ 12 clerk-judges – suggests that a relatively small number of judges are having outsized influence on the composition of the federal bench. And, based on the numbers, this leans principally in a conservative direction.

What next?

Looking forward, several questions demand attention. Will this trend continue to accelerate? Relatedly, will judges who lack Supreme Court or prominent circuit clerkships find their paths to the bench increasingly blocked? And will the public’s perception of judicial independence suffer as a result?

Of course, the data presented here captures only a moment in the evolution of the federal judiciary – a moment when the clerk pipeline has become sufficiently visible to analyze. But as Trump’s second administration considers judicial appointments, and as sitting justices contemplate their retirement timing, these patterns of succession will likely intensify.

What seems most certain is that the era of unpredictable judicial appointments – when Republican presidents might appoint liberal justices or when judges might dramatically evolve on the bench – is largely over. The clerk pipeline, combined with more sophisticated vetting processes and strategic retirement decisions, has made judicial appointments far more predictable. We know not just what ideology a nominee holds, but where they learned it, from whom, and how they are likely to apply it. The federal judiciary is thus becoming, for better or worse, a self-perpetuating institution in which each generation of judges carefully selects and trains the next.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS, Recurring Columns