Supreme Court behavior on the shadow docket

Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

Please note that the views of outside contributors do not reflect the official opinions of SCOTUSblog or its staff.

For most of the Supreme Court’s modern history, its orders – which, unlike the court’s opinions, are typically short, unsigned, and decided without formal briefing and oral argument – lived in the background. Orders were considered dense, technical, and largely ignored outside the small community of lawyers who practice regularly before the court. That changed over the last decade, however, as the court began deciding increasingly important cases through orders rather than on its merits docket – the cases in which the court receives full briefing, hears oral argument, and issues traditional opinions.

In 2015 William Baude supplied both the name – “shadow docket” (though many different ones have been suggested) – and a caution: Such orders do not always match the “high standards of procedural regularity” associated with argued cases. Stated another way, cases on the shadow docket do not involve the “consistency and transparency of the Court’s [ordinary] processes.” But, as Steve Vladeck has emphasized, the stakes in these cases can be huge. From immigration and elections to abortion, the death penalty, religious liberty, and administrative power, the court increasingly shifts national policy through these rulings, which are often unseen, unsigned, and almost always unexplained.

An example from earlier this year illustrates this. On July 14, in McMahon v. New York, the court granted the government’s emergency request to pause a district-court injunction that had blocked the Trump administration’s effort to wind down the Department of Education. The order was brief and unsigned; three justices – Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson – issued a lengthy dissent warning that allowing mass terminations to proceed risked letting the executive “repeal statutes by firing all those necessary to carry them out.” Whatever one’s view of the merits, the mechanics mattered: a major national policy shifted through an emergency order in which the majority’s reasoning consists of four sentences, with legal argument only visible in dissent.

With an increase in activity on the shadow docket, it is all the more important to understand how the justices make decisions on it. That is what this article set out to do through the lens of dissenting votes.

Methods used

The data for this article goes from October 2010 through May 2025. According to docket counts organized by Professors Jonathan Kastellec and Anthony Taboni, the Supreme Court during this period issued orders or decisions in 93,832 filed cases that were not fully briefed and argued. Within this set of decisions, a small subset of 387 garnered public dissenting votes. The dissenting coalitions are noted by their votes.

Although we don’t know with certainty that the justices who do not publicly dissent agree with the majority, we know that they did not actively vote to dissent. Given this, I group them the same way as I would group the court’s majority in a decision in which each justice signs on to a position in the majority or dissent.

What the data show

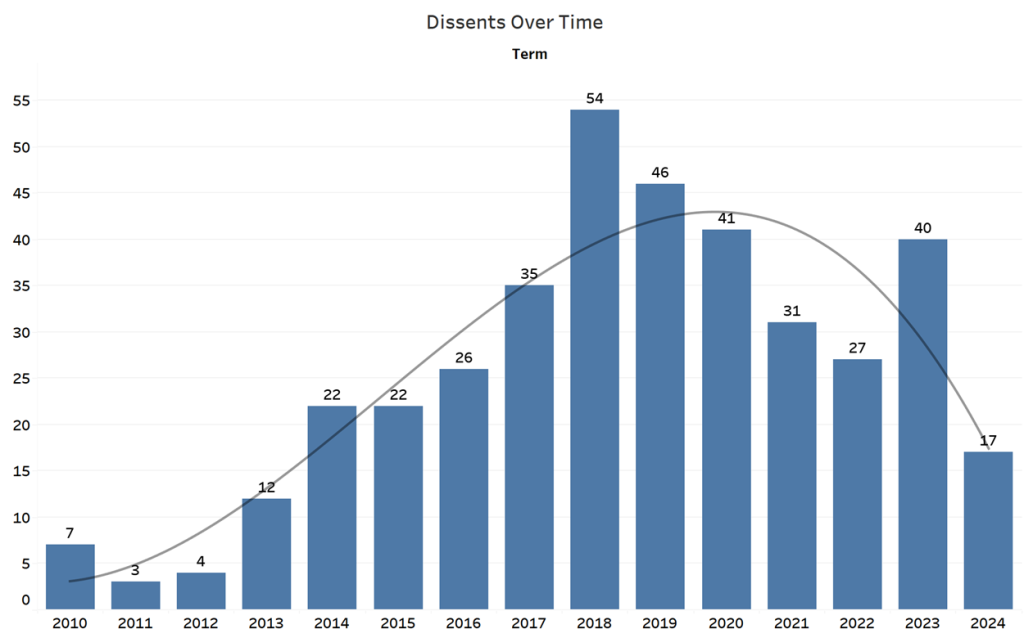

Dissents surge and then cool. In 2010, we see few dissents, likely reflecting the court’s spare use of the shadow docket for important decisions. Dissents notably increase in the 2014-15 term (a year before Baude’s article bringing the shadow docket to light), and then hit a high-water mark in the 2018-19 term with 54 dissents. This is followed by elevated levels through the 2020-21 term before curiously dropping and then rising again in the 2023-24 term.

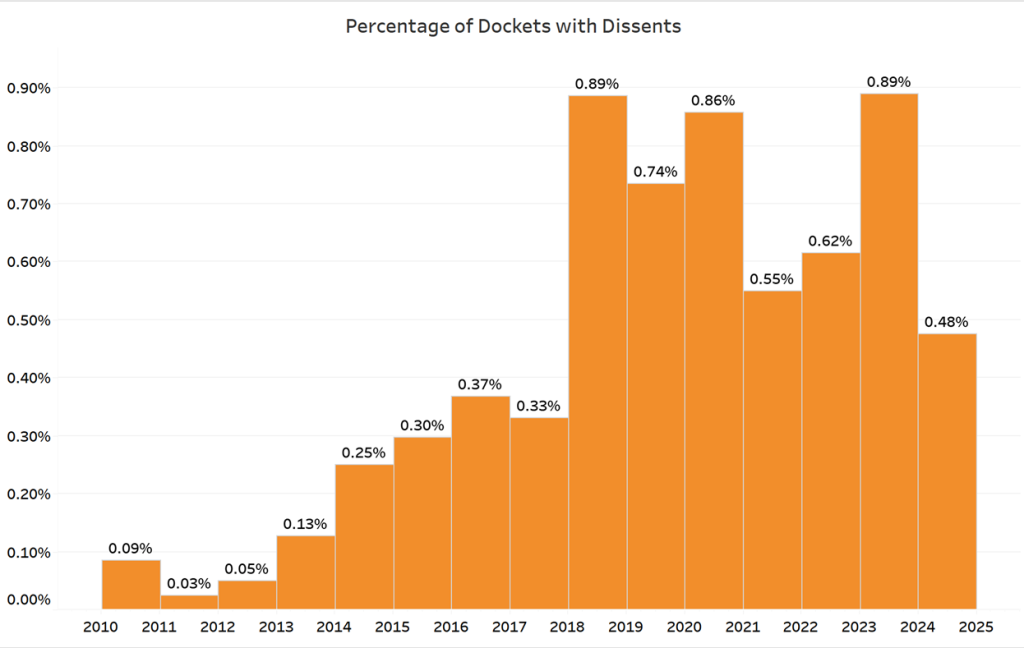

Measured as a share of the entire shadow docket, the percentage of dissents hits highs of about 0.89% in the 2018-19 term and again in the 2023-24 term, then drops to approximately 0.48% in the 2024-25 term. Quantitatively speaking, dissents are thus exceedingly rare on the shadow docket.

Who dissents — and with whom

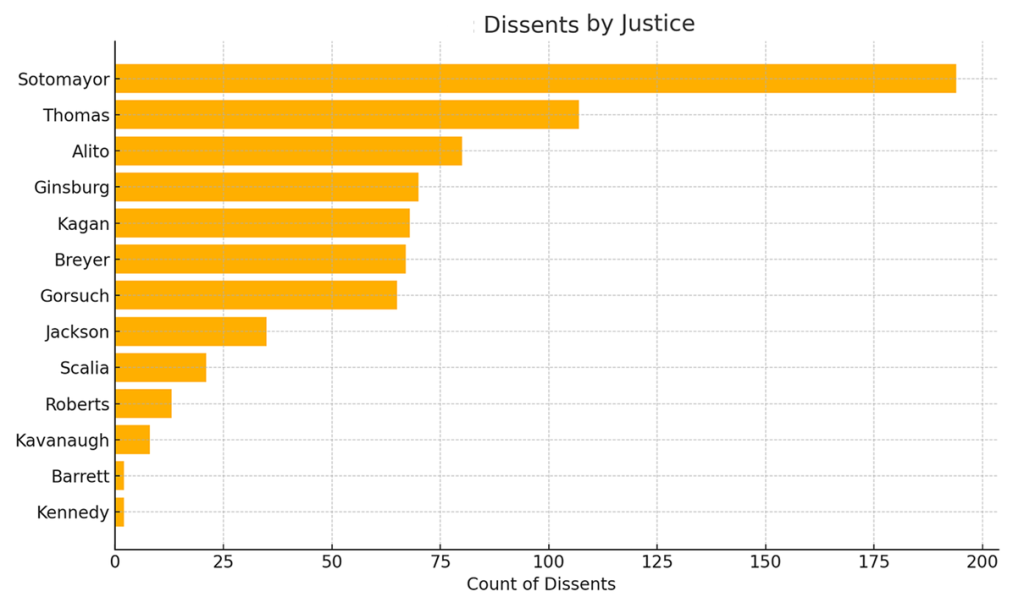

The poles are familiar. Sotomayor is the era’s dominant dissenter (194). On the right, Justices Clarence Thomas (107) and Samuel Alito (80) lead, with Justice Neil Gorsuch (65) following. Earlier liberal totals are driven by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg (70), Elena Kagan (68), and Stephen Breyer (67); Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson (35) rises quickly in later years.

Seeing what justices co-dissented confirms this. The most frequent co-dissents are by Sotomayor–Kagan (67) and Ginsburg–Sotomayor (66) on the left and Thomas–Alito (58) on the right. Breyer–Sotomayor (51) and Breyer–Kagan (36) also commonly co-dissented.

Dissent coalitions, term by term

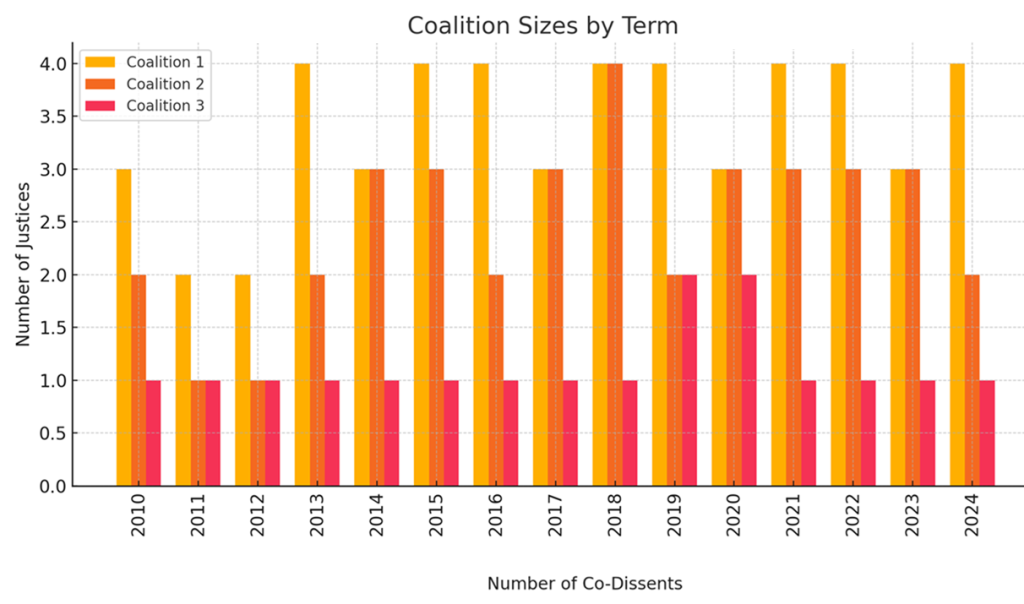

Focusing only on dissents leads us to ask a simple question: Who objects together when the court acts? Again, and unsurprisingly, most years resolve into two clear blocs. The liberal side features Sotomayor and Kagan together (with Ginsburg earlier and Jackson later). The conservative side centers on Thomas and Alito, often with Gorsuch; Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett join depending on the term. Chief Justice John Roberts is the most variable conservative, sometimes joining the left and sometimes the right.

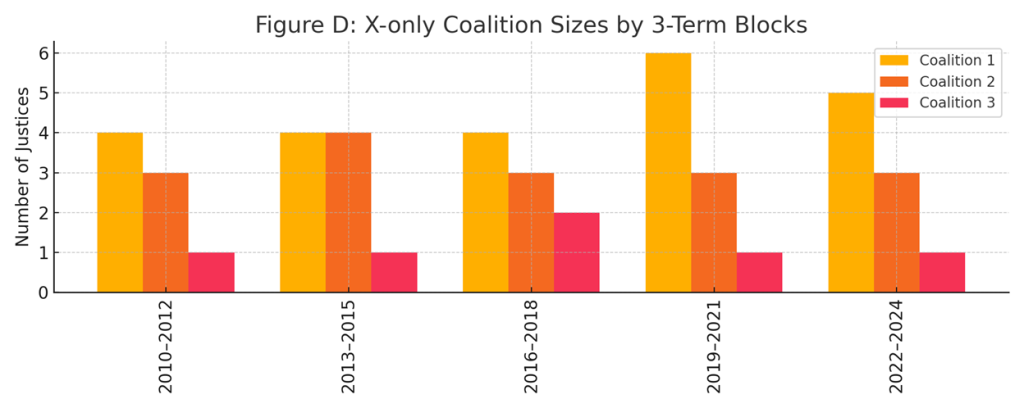

Using non-overlapping three-term windows, which “smooths” out the data, shows a similar pattern: on the left, Sotomayor/Kagan are often in dissent (with Ginsburg joining them early on and later Jackson); and, on the right, Thomas/Alito (often with Gorsuch) aligned in dissent.

Where the left–right line bends

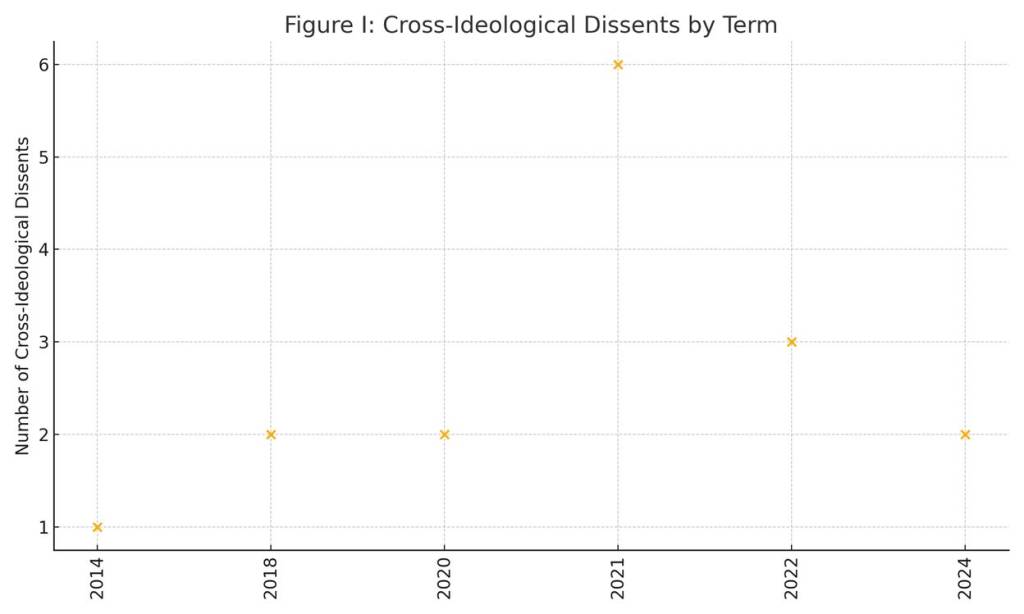

Cross-ideological dissents – at least one conservative and one liberal dissenting together – are rare but perhaps more revealing. There are 16 instances of these, about 4% of all dissents, in the time period studied. They cluster in a few standout terms, notably the 2020-21 term, and often feature Roberts or Gorsuch dissenting alongside the liberals (Breyer, Kagan, Sotomayor, and later Jackson).

These moments flag issue-specific fractures where emergency posture or institutional concerns cut across the usual alignment. With regard to Roberts, for example, he took part in cross-ideological dissents in several of the COVID-19 decisions and in decisions on other rights-related issues, including ones related to the environment. For Gorsuch, these included several applications in indigenous law cases that were later resolved with oral arguments, as well as with cases in the criminal law domain.

The story in short

Across lenses and years, the court’s shadow-docket behavior, at least when it comes to dissents, is generally a stable left-right system: Sotomayor/Kagan (with Ginsburg earlier or Jackson later) on one side, and Thomas/Alito (often with Gorsuch) on the other; Kavanaugh/Barrett typically extend the conservative pole; Roberts sometimes peels off in specific disputes. The fact that there are only a handful of cross-ideological dissents underscores the narrative of the ideological stability in these decisions.

What makes this analysis useful is that it maps how the court actually behaves on the shadow docket, not just in merits cases. Under time pressure and limited briefing, the justices’ patterns of dissent reveal who moves together when it matters most. The coalitions identified here show a durable left–right structure and the subtler instincts behind it. For readers trying to anticipate outcomes, this offers a practical picture of the court’s operational majority and its fault lines – insight you can’t get from merits votes alone.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS, Recurring Columns

Cases: McMahon v. New York