Why equal protection can’t be settled by biology and statistics

Please note that SCOTUS Outside Opinions constitute the views of outside contributors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of SCOTUSblog or its staff.

Last month, the Supreme Court held oral argument on two landmark anti-discrimination cases: Little v. Hecox and West Virginia v. B.P.J. The states in these cases – Idaho and West Virginia – passed laws categorically banning trans girls from playing on girls’ sports teams. Two trans girls who underwent gender-affirming medical treatments while young challenged the laws as a violation of the equal protection clause and Title IX, which prohibits discrimination “on the basis of sex” in “any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

One of the most striking things about oral argument was that both sides agreed on quite a lot. Both sides agreed that the states’ laws are sex-based classifications that would have to be “substantially related” to an “important governmental interest” to pass constitutional muster. And both sides argued as if once an important governmental interest is in play, biological and statistical facts alone can determine whether or not a law is “substantially related” to the important governmental interest.

But we think that relying on biological and statistical facts to try to argue (for or against) an equal protection claim in this way is a bad strategy. It is a bad strategy for two reasons.

First, as we argue below, neither side’s argument can succeed on grounds of biological and statistical facts alone. Whether a sex classification is “substantially related” to an “important governmental interest” – and thus constitutionally permissible – is an irreducibly normative question. In the context of these cases: it is a question about how the category of sex should operate in organizing sports. Biology and statistics alone cannot provide the answer.

Second, and relatedly, we predict the confused legal argumentation from the parties will translate to an unprincipled judicial decision. The decision will be – as the court’s decision in United States v. Skrmetti was – a (wordy) declaration of a winner lacking coherent justifying reasoning.

Here, in a nutshell, is what each side argues.

For brevity we focus on the equal protection arguments, but the Title IX arguments are similar.

The first step in the states’ argument is to grant that their laws banning trans girls from playing on girls’ sports teams classify on the basis of “sex.” Second, the states argue that equal protection does not prohibit the use of sex as a category; it allows uses that are “substantially related” to achieving an “important governmental interest.” The states assert a governmental interest in advancing “girls’ and women’s athletic opportunities and . . . fairness and safety in girls’ and women’s sports.”

Their chosen means of promoting that end is to segregate sports by a “biological” definition of sex in which membership is determined by immutable, biological facts. Specifically, West Virginia defines “sex” as “based solely on the individual’s reproductive biology and genetics at birth,” and Idaho says “sex” can be verified by only one or more of “reproductive anatomy, genetic makeup, or normal endogenously produced testosterone levels.” While neither law is clear about how different kinds of biological facts are together meant to be determinative of “sex,” for simplicity, we might model the states’ classificatory schemes as defining a person as “female” if and only if they have XX sex chromosomes, and “male” if and only if they have XY sex chromosomes. Finally, the states say that their chosen means is substantially related to the achievement of their governmental interest. According to the states, sex chromosomes “determine the factors most relevant to [sports] performance.” It is a matter of “biological reality” that, in general, “males are . . . bigger, faster, and stronger” than females.

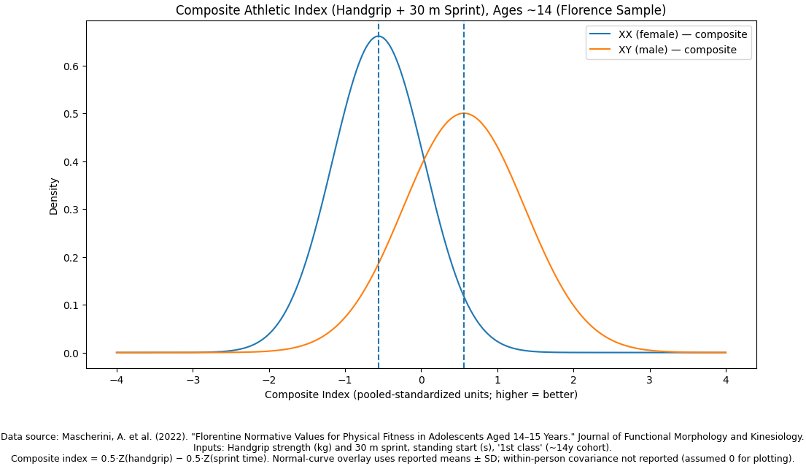

Since the states assert a governmental interest already framed in sex-specific terms, they start by asking about the distribution of athletic ability between groups defined by sex. The states’ argument can be illustrated by positing something like the figure below, representing the XX and XY distributions of some index of measured athletic ability. (Note that the chart is conceptual and not meant to express any particular empirical statement.)

The states point to a statistical fact – that the XY distribution of athletic ability is to the right of the XX distribution – which, they maintain, reflects a biological fact – “inherent differences” between men and women. According to the states, these facts establish that segregating sports teams by their so-called biological definition of sex is substantially related to the interest of advancing “girls’ and women’s athletic opportunities and . . . fairness and safety in girls’ and women’s sports.”

Somewhat surprisingly, the challengers’ argument has a very similar structure.

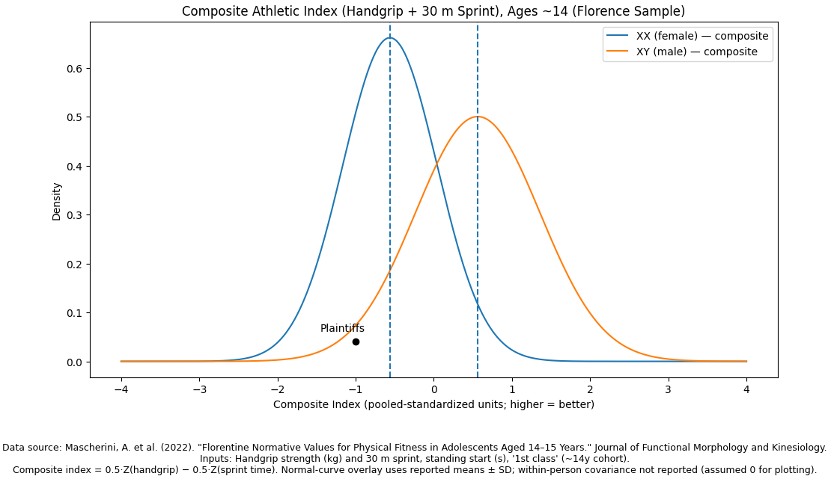

The challengers grant (perhaps for purposes of argument) that it is an accurate generalization to say that people with XY chromosomes have higher measured athletic ability than do people with XX chromosomes. But the challengers also advance their own statistical fact: Trans girls and women who have undergone certain gender-affirming medical treatments while young fall on the far end of the XY distribution that overlaps with the XX distribution. And the challengers also maintain that this statistical fact is based on a biological fact: the challengers have “lower[] . . . circulating testosterone levels” that “affect[] . . . bodily systems and secondary sex characteristics,” including by “decreas[ing] . . . muscle mass and size.”

The challengers’ argument can be illustrated by placing a dot on the chart to represent the athletes who, despite having XY chromosomes, do not have the “physiological characteristics associated with athletic advantage between cisgender men and cisgender women.”

As the challengers see it, excluding them, and trans girls like them, from playing on girls’ sports teams is not substantially related to advancing the states’ goals because as a matter of “biological reality,” they are on the far left of the XY distribution.

To sum up, both sides are pointing to different features of the same chart. The states point to the XX versus XY distribution of athletic ability. The challengers point to the dot representing trans girls or women with low circulating levels of testosterone – levels in virtue of which they fall on the left tail of the XY athletic ability distribution overlapping with the XX distribution. Both sides argue that there is a statistical fact, based on “biological reality,” that determines whether the law is substantially related to an asserted governmental interest, and thus, that determines whether the law is constitutional.

The problem with these arguments

An inquiry into whether a classification is “substantially related” to an important governmental interest cannot be settled based on assertions about statistics and biology, even if those assertions are true.

Each side already sees the issue, but only with respect to the other side’s argument. Let’s start with the states’ response to the challengers.

The states criticize the challengers for demanding a “perfect fit” between a classification and achievement of a governmental interest. The states note that some people with XY chromosomes who identify as boys may have “naturally low athletic abilities” or “take medication that lowers their testosterone levels.” Some of these people may even be located to the left of the challengers on the figure above – a statistical fact that would be based on biology. The states point out that according to the challengers’ logic, barring these people from girls’ teams would be unconstitutional. According to the states, more would be unconstitutional than the challengers would be willing to admit.

The challengers find a similar problem with the states’ argument. The challengers point out that according to the states’ logic, “overbroad generalizations about the sexes” would be constitutional, so long as they are “accurate for most people.” Consider a hypothetical adapted from oral argument. Say that the XY distribution of mathematical ability fell to the right of the XX distribution of mathematical ability. In order to advance the important governmental interest of allowing advanced students to excel at a faster pace and allowing less advanced students more time to learn, schools decide to segregate math classrooms by sex chromosome. If we grant the statistical fact about the XX versus XY distribution of mathematical ability is based in “biological reality,” the state would be forced to conclude that segregating math classrooms by sex chromosome is substantially related to an important governmental interest. According to the challengers, more would be constitutional than the states would be willing to admit.

The states’ and the challengers’ arguments prove too much and explain too little. Nothing internal to their arguments gives them the resources to make the distinctions they want to make.

What both sides need is to invoke a principle for when sorting by sex is normatively bad and when it is instead normatively appropriate. Any sex-based equal protection challenge (indeed any equal protection challenge) asks whether a given use of the category – call it a “classification,” “generalization,” or a “stereotype” – advances or hinders how we want that category to operate in our society. The real principle at issue in these cases concerns how we want sex to operate as a social category.

The need to appeal to claims about how sex should operate as a social category is clear from the jump. Look at how the states frame their governmental interest: as advancing “girls’ and women’s athletic opportunities and . . . fairness and safety in girls’ and women’s sports.” The governmental interest already presupposes the value of a sex classification. In so doing, they assume competition between members of the same “sex” group is fair and safe irrespective of individual variation within the group, and that competition between members of different “sex” groups is unfair and unsafe. Fairness and safety in sports, the states maintain, is preserved if competition is limited to people who are “similarly situated” with respect to each other. But what it takes for people to be “similarly situated” with respect to sports is not to be within some range of measured athletic ability. It is to share a trait that the states believe defines sex membership. Boys are similarly situated to boys because they are boys, and girls are similarly situated to girls because they are girls.

Why do the states think fairness and safety can be secured so long as girls compete against girls, even though some girls will be much “bigger, faster, and stronger” than others? Why does neither side propose to organize sports directly on the basis of measured athletic ability, as opposed to some very noisy proxy for it? The answer to these questions must depend on some positive vision for the social category “girls,” and the states must think that segregating sports teams will change or maintain that social category in a way they value.

Put another way: The real disagreement between the parties, and between the justices that will decide these cases, lies in value judgments about social categories and how they operate. It is not a disagreement about how “accurate” the link is between sex and athletic ability – the focus of so much of the parties’ argument. Allowing trans girls on girls’ sports teams changes the social meaning of both sex and sports, just as allowing gays to marry changed the meaning of sex and marriage. It rewires how we think that some biological trait is related to some social practice. Some of us think that change is good, others think it is bad. In any case, the real principles driving our positions should be put into the light, where the public can see them.

Values are contentious. Courts are notoriously squeamish about making value judgments, preferring to leave such things up to the legislative branches. But in trying to strip anti-discrimination law of all its normative bite, we lose sight of what the constitution demands courts decide.

The authors thank Robin Dembroff for helpful comments on this article.

Posted in Court Analysis, Featured, SCOTUS Outside Opinions

Cases: Little v. Hecox (Transgender Athletes), West Virginia v. B.P.J. (Transgender Athletes)