Which Supreme Court cases are actually important?

It’s the age-old question: Does the Supreme Court decide its cases based on rank partisanship rather than legal principles?

Many scholars and commentators unhesitatingly answer in the affirmative. Such individuals may acknowledge that the plurality of Supreme Court decisions are unanimous (42% last term) and that the vast majority of the court’s cases do not break down by the 6-3 conservative/liberal split (over 90% last term). But, in their view, the important cases are decided along partisan lines.

Of course, this raises the obvious follow-up: Which cases are the important ones? In answering this, many look no further than the press. The New York Times will often feature the most seemingly influential decisions on its front page, while The Congressional Quarterly annually depicts certain selected cases as landmark rulings. Others may point to the court’s vote itself as evidence of importance, particularly when the cases fall along the aforementioned 6-3 divide. More sophisticated approaches, such as in Adam Feldman’s recent article, have combined multiple measures to estimate importance.

Apart from Feldman’s piece, the problem with using these factors to assess the most important cases is, I think, obvious. With regard to the former, this only highlights important cases after the fact and thus tells us nothing about what are likely to be the most important cases before they are decided. Concerning the latter, as legal commentators such as Sarah Isgur have suggested, this renders the entire debate circular: we know a case was important because the vote was 6-3, and the vote was 6-3 because it was, well, important.

Based on insights from economics, I would like to propose a different metric: the number of amicus curiae, or “friend of the court,” briefs filed for each case. And when we use this metric, I think we get some interesting insights into Supreme Court decision making.

The art of amici

As most SCOTUSblog readers know, amicus curiae briefs are court filings submitted by third parties who seek to persuade and inform the court about the outcome of a particular case.

In my field, economics, the market value, or importance, of an asset is determined by how much other people are willing to pay actual money to purchase it. If many people are willing to purchase it, they are providing a meaningful signal of their interest to the market rather than simply making cheap talk; this is because they are quite literally putting their money where their mouth is. Of course, this does not apply perfectly to amici, as the court generally allows anyone to file such a brief if so desired. But preparing such briefs still requires time and effort, costs money (both for the drafting of the brief and to print it on the booklet form that the court requires), and puts the reputation of the party filing it at stake. An amicus that submits a shoddy or pointless brief runs the risk that the court will ignore its future filings.

Because of the effort and reputational stakes, filing an amicus brief is a credible signal that the filer thinks this case is worth the effort and risk. And if many amici all do the same, it is a signal that the case may hold considerable weight. Finally, because amicus briefs are filed before the case is decided, this metric avoids the circularity problem identified above.

Counting the number of amicus briefs is not a perfect method to determine a term’s most important cases. It’s likely that other factors, in addition to case importance, get the attention of the amici. For instance, researchers have previously found that civil liberties cases tend to receive more briefs. Other factors like legal complexity, under-resourced litigants, or inexperienced attorneys are also known to attract more amici.

Given all this, I think it’s important to emphasize how the number of amicus briefs shouldn’t be used. First, small differences in briefs probably don’t tell us much about relative importance. Although very large differences in briefs might be informative, cases with 50 briefs shouldn’t be considered more important than ones with 45, for example; in this context, a difference of five is little difference at all.

Secondly, there will be outliers. In most years the case with the highest number of amici vastly outstrips every other case that term. For example, in the 2023-24 term, City of Grants Pass v.Johnson had 110 briefs, while Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo a “mere” 70. Both cases were clearly important, but it’s not at all clear that the case on whether enforcing anti-vagrancy laws violated the “cruel and unusual punishment” clause of the Eighth Amendment was more important than how much deference courts should give to an agency’s interpretation of its statutory authority (and overturn major precedent in doing so).

Because of these consistent outliers, looking solely at only a few cases with the most briefs offers only limited – although still interesting – insights into important cases.

The top cases

To isolate what recent cases this metric would predict as the most important, I determined the number of amici for all cases from the last three full Supreme Court terms. I then isolated the five cases per term that received the most such briefs. This resulted in the following findings:

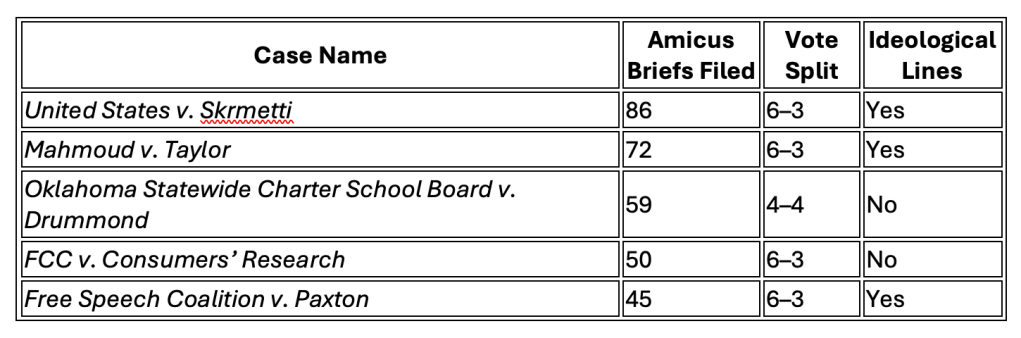

Supreme Court cases 2024–25 term:

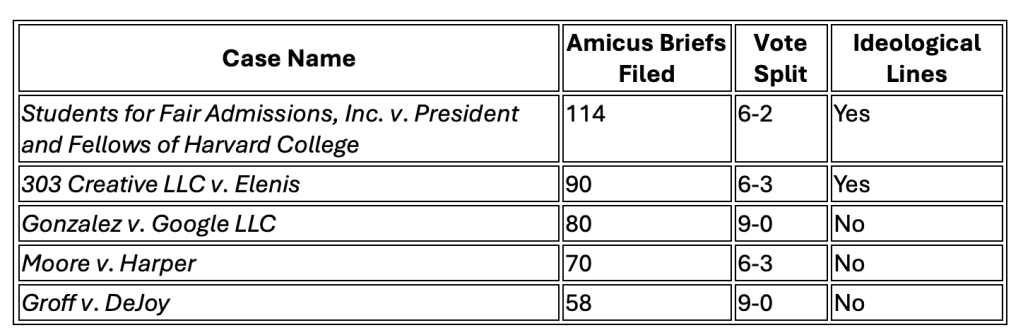

Supreme Court cases 2023–24 term:

Supreme Court cases 2022–23 term:

On a per term basis, United States v. Skrmetti (whether a state could ban certain medical treatments for transgender minors), City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, and Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard College(whether affirmative action in college admissions violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment) yielded the most amici.

There are (at least) three things worth noticing about these cases. First, all three cases were related to civil liberties. Second, all three cases have large gaps in the number of amicus briefs when compared to the cases just a few ranks lower. And, finally, all three cases were decided along ideological lines. That doesn’t tell the whole story, however. Expanding out to the top 15 cases (that is, the top five cases with the most amicus briefs per term), the data changes significantly. Forty percent of these cases were decided unanimously, and nine of them (60%) were not decided along ideological lines.

The outcome of many of these cases also highlights the difference between looking at importance before or after we know the outcome of a given case. Several cases, like FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (87), garnered significant attention because the question presented was important. But since the court decided the case without changing the status quo (in that situation for a drug widely used for abortion and contraception), it looks less important with the benefit of hindsight. And focusing only on the cases where the court decided to act misses the times when the court deadlocked or declined to make a change. Oklahoma Statewide Charter School Board v. Drummond (59), which was concerned with whether public charter schools could be run by a religious entity, and NetChoice, LLC v. Paxton (82), Moody v. NetChoice, LLC (84), and Gonzalez v. Google LLC (80) – which were all on government restrictions of speech in social media – were cases in which not much changed despite the clear importance of the question being considered. Lastly, while allowing Trump to remain on the ballot for the 2024 election in Trump v. Anderson (76) wasn’t technically maintaining the status quo, deciding the other way would also have given the case far more impact.

What’s missing

SCOTUSblog readers will – and should – focus on those cases not included in the top five. Perhaps most prominently among these are Trump v. CASA (28), which partially restricted federal courts’ authority to issue universal injunctions; Trump v. United States (44), which held that a president has broad immunity from criminal prosecution for some acts directly authorized by the Constitution; Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (70), which, as noted above, reduced the deference courts give to an executive agency’s interpretation of the law that it administers; and Biden v. Nebraska (35 briefs), which held that the Department of Education was not authorized to forgive about $430 billion in student loan debt using a 2003 law.

As an initial matter, the amicus metric still clearly designated these cases as important. Their number of amicus briefs was well above the typical case that term (10-14). And some of them, especially Trump v. CASA, were a product of unique circumstances. Originally filed as an application on the court’s “emergency docket,” CASA was set for oral argument quite late in the term and gave amici only 12 days to file their briefs (whereas in a normal case they would have a minimum of six weeks). Trump v. United States also gave potential amici less time than normal to file briefs (only 19 days), although the time constraint was not as extreme as for CASA. But the biggest factor missing from these cases may have been that, unlike our “winners,” they did not (at least directly) address civil liberties, which, as noted above, tend to attract a disproportionate number of amici.

With that in mind, I reviewed all those cases that had more amicus briefs than the median for all three terms. What I found was striking. For the 2024-25 term, 25 of the 30 (83%) above-median cases were decided along a non-ideological divide. In the 2023-24 term this came out to 18 of 27 (67%), and in the 2022-23 term 23 of 26 (88%). Across all three terms, almost 80% of the cases with a large number of amicus briefs were thus decided along non-ideological lines.

The current term

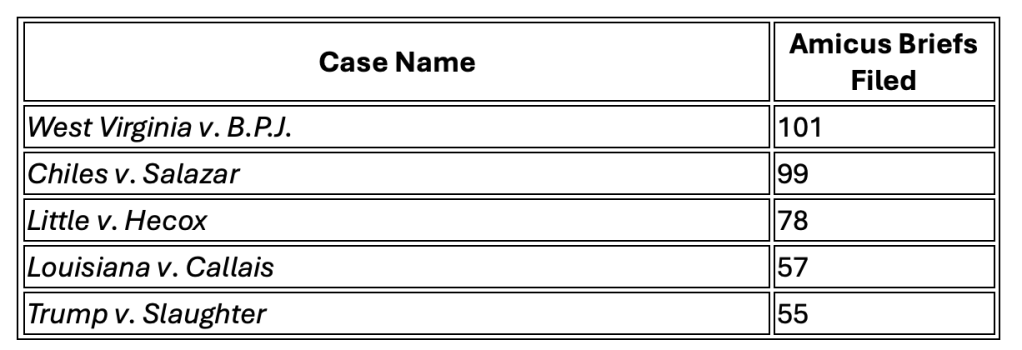

Although the court has not granted all of its cases for the 2025-26 term, and not all cases have passed the deadline for submitting amicus briefs, I collected the current leaders for this term to provide a preview of – based on this metric – the most important cases granted so far. (This is current as of December 11, 2025.)

This resulted in the following breakdown:

This list is not particularly surprising: three of these cases touch on controversial “culture war” issues related to civil rights, and another one (Louisiana v. Callais) will likely have major implications for the Voting Rights Act.

Perhaps the most prominent absence is Learning Resources, Inc. v. Trump, the challenge to Trump’s power to levy tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, which just barely missed the top five with 47 briefs. But like CASA, Learning Resources was an expedited case that gave reduced time to file amicus briefs.

Conclusion

Using the number of amicus briefs to determine which cases are the most important provides several interesting insights.

First, the cases that one would expect to be considered important or potentially important do appear to have more amicus briefs than a “typical” case. That said, certain case characteristics, particularly cases touching on civil rights issues, generate a disproportionate number of amicus briefs.

Second, and perhaps more notably, there is mixed evidence for the popular narrative that the most important cases are decided along ideological lines. In each of the last three terms, the case with the highest number of amicus briefs had the familiar conservative/liberal split. When looking at the top 15 cases, however, only 40% were decided along ideological lines. And when expanding out to all above-median cases, only roughly 20% were decided ideologically. This tells us that the public’s perception of a 6-3 court in the most important cases may be real, but it is also overstated.

Posted in Court Analysis