Two centuries of declining judicial agreement

Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

When Chief Justice Earl Warren was able to achieve unanimous agreement in Brown v. Board of Education, he demonstrated the Supreme Court’s capacity to speak with a single, authoritative voice on foundational constitutional questions. Today’s court appears to operate in a starkly different terrain. Multiple publications have characterized the Roberts court as the most polarized in generations, with recent decisions on abortion, affirmative action, and gun rights fracturing along predictable ideological fissures.

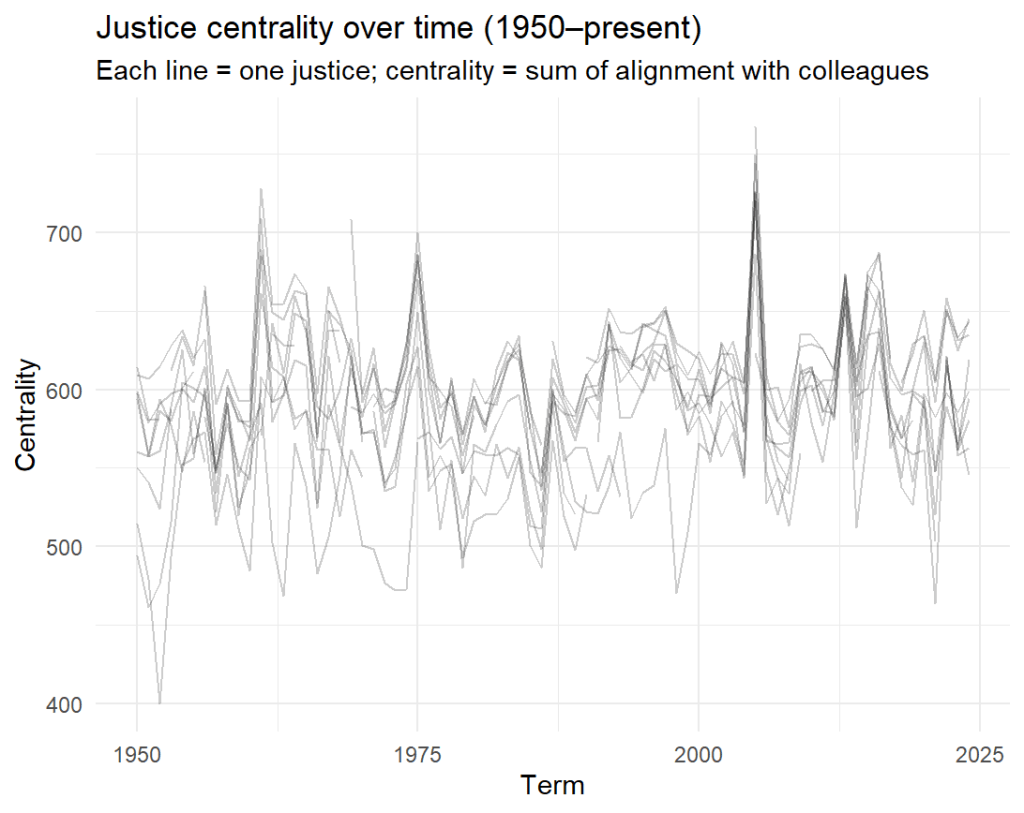

Using comprehensive data on the justices’ agreement rates from 1791 to 2025, we can now trace how justices form coalitions and when these drift apart. This analysis reveals not just whether justices agree, but the dramatic transformation in how much they agree – and disagree – across American constitutional history.

And this comes at a critical moment. The court recently agreed to hear a case on President Donald Trump’s challenge to birthright citizenship. This will further test whether today’s conservative supermajority can achieve Warren-style unanimity, whether it will rely on ideologically-based voting blocs, or whether it will splinter in a different direction entirely.

The great divergence: polarization across time

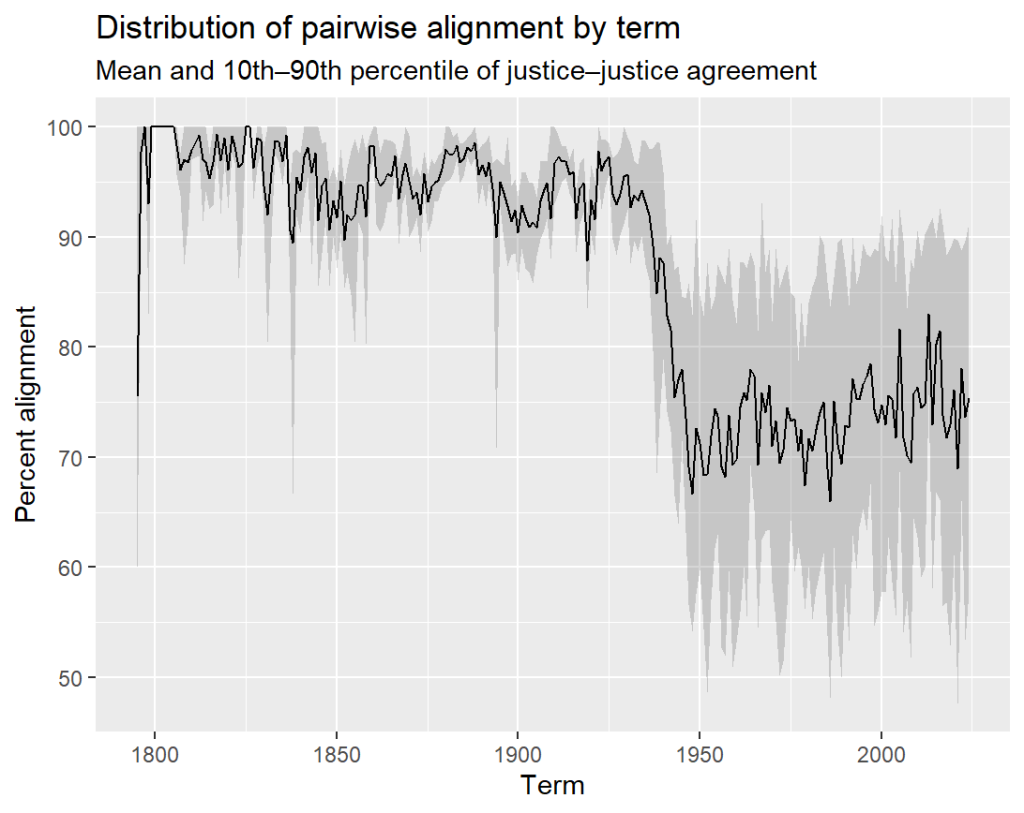

The following visualization captures the court’s transformation across two centuries:

As this data reveals, from 1800 through the 1930s, the justices broadly agreed with one another (90-100% of the time), and this was regardless of the appointing president or party. But a dramatic inflection point arrived in the 1930s and 40s. The reason for this is not entirely clear, but some suggest it is due to a legacy started by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who was seen as the first regular dissenter on the court, spurred on by Chief Justice Harlan Fisk Stones’ positive outlook on such behavior, and then turbocharged by the conservative-liberal split on the New Deal court. From then on, the frequency of agreement began a steady descent, accelerating through the 1960s and 70s, and ultimately “stabilizing” around 70-75% of the time in the modern era. More significantly, the extent of this disagreement exploded. Where 19th-century courts showed tight agreements between justices, more modern courts exhibit an enormous divergence.

This widening gap paints a (now familiar) picture of polarization at its essence, with some justices agreeing almost perfectly while others disagreeing even more than they agree.

Extreme alignments: the closest and most distant pairs

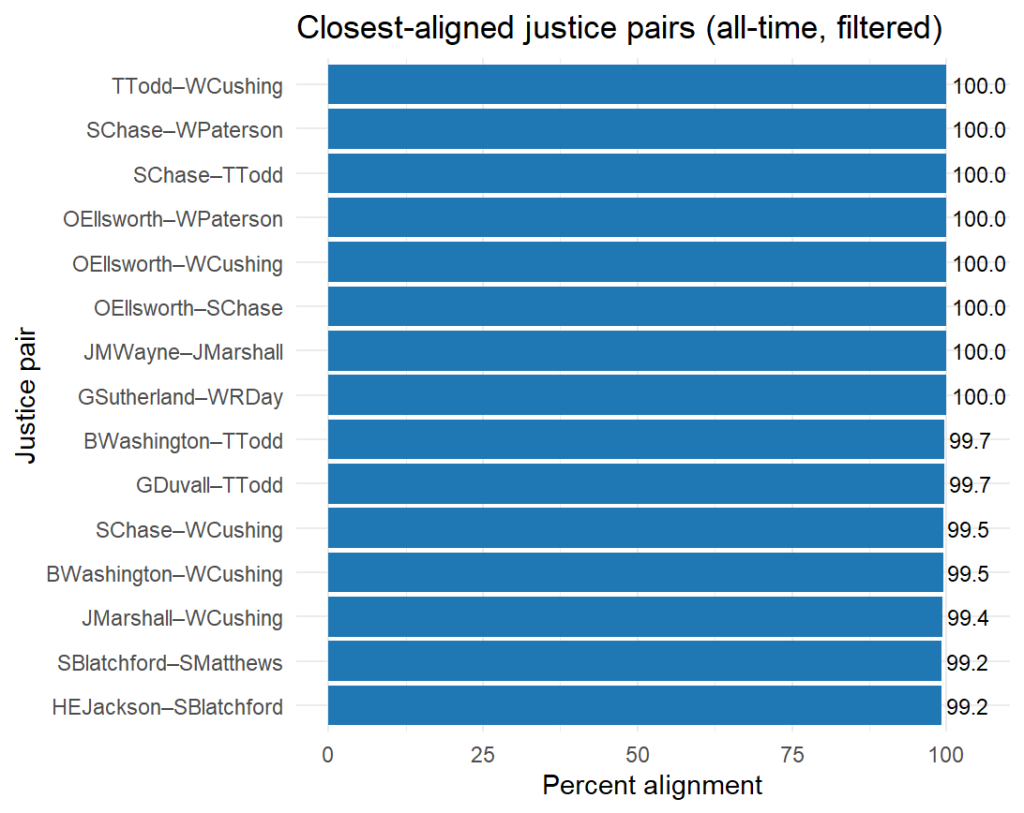

For those history buffs among us, we can also break down what specific justices agreed the most. As noted, early justices achieved near-perfect agreement, with some, such as Justices Thomas Todd and William Cushing, as well as Justices Samuel Chase and William Paterson, actually agreeing in every single case before them. These extraordinary rates reflect a smaller, more cohesive court operating within narrower jurisdictional bounds on what cases could and could not be heard.

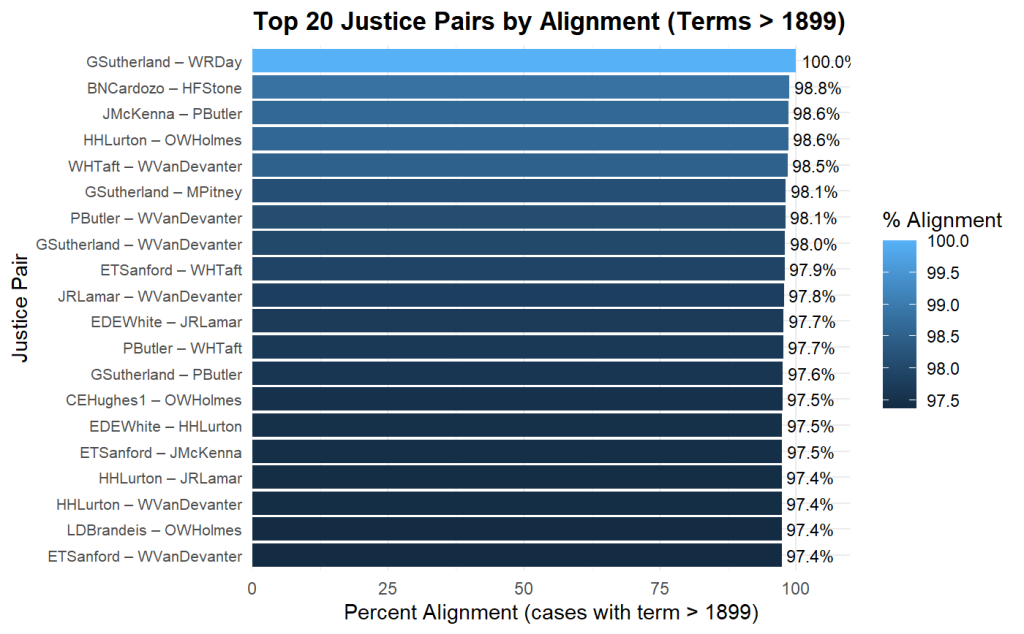

Moving to the 20th century, the strongest alignments (for justices with votes in at least 20 shared cases) principally come from earlier in the century. Justice George Sutherland’s perfect alignment with Justice William R. Day and near-perfect alignment with Justices Willis Van Devanter, Pierce Butler, and Mahlon Pitney captures the core of the court’s conservative, pro-business wing that dominated in the 1910s and 20s and later formed part of the “Four Horsemen” against the New Deal.

The White and Taft courts (1910-1921 and 1921-1930, respectively) loom large here – Chief Justice Edward Douglass White, and Justices Horace Lurton, Joseph Lamar, and Edward T. Sanford were appointees of Presidents Warren G. Harding and William Howard Taft (before he became chief justice) who generally favored restrained federal intervention and strong property and contract rights. It is thus unsurprising that pairs of these justices almost always voted in lock step. On the more progressive side, Justice Benjamin Cardozo’s near-uniform voting record with Chief Justice Harlan F. Stone reflects their famous civil-libertarian and regulatory coalition that coalesced in the 1910s-30s (and earned them, along with Justice Louis Brandeis, the nickname the “Three Musketeers”).

These pairs all line up neatly with historically recognized ideological teams on the White, Taft, and early Hughes courts, where justices shared appointing presidents, partisan backgrounds, and broadly similar views on federal power and economic regulation.

The least-aligned pairs perhaps better reflect the court’s polarization. As the chart above reveals, in contemporary times, Justices Clarence Thomas and Ketanji Brown Jackson – the court’s current ideological opposites – have agreed in just 57.3% of cases. But this relative rate of disagreement is not new: Justices John Paul Stevens and Samuel Alito, for example, managed to agree only 57.1% of the time. And historical context matters: The ultra-liberal Justice William O. Douglas’ conflicts with the court’s conservatives produced sub-50% agreement rates.

Indeed, the graph above further illustrates the shifting identities of voting pairs. The 1950s featured Justices Stanley Reed (a fierce conservative on certain issues) and William O. Douglas (a fierce liberal on the vast majority of issues) as disagreeing in a striking amount of cases. The 1960s-70s saw the conservative Justice William Rehnquist and Douglas (again!) claim the bottom position, reaching an extraordinary 43.2% in one term – disagreeing significantly more than agreeing.

Another interesting pattern emerges by looking at this data: while top-pair agreements (justices agreeing with one another) have remained remarkably stable – in the 90-100% range across seven decades – bottom-pair agreements (justices disagreeing with one another) have fluctuated wildly. This shows a fundamental asymmetry: ideologically similar justices reliably vote together, but cross-ideological disagreements have varied in intensity.

The disappearance of bridge justices

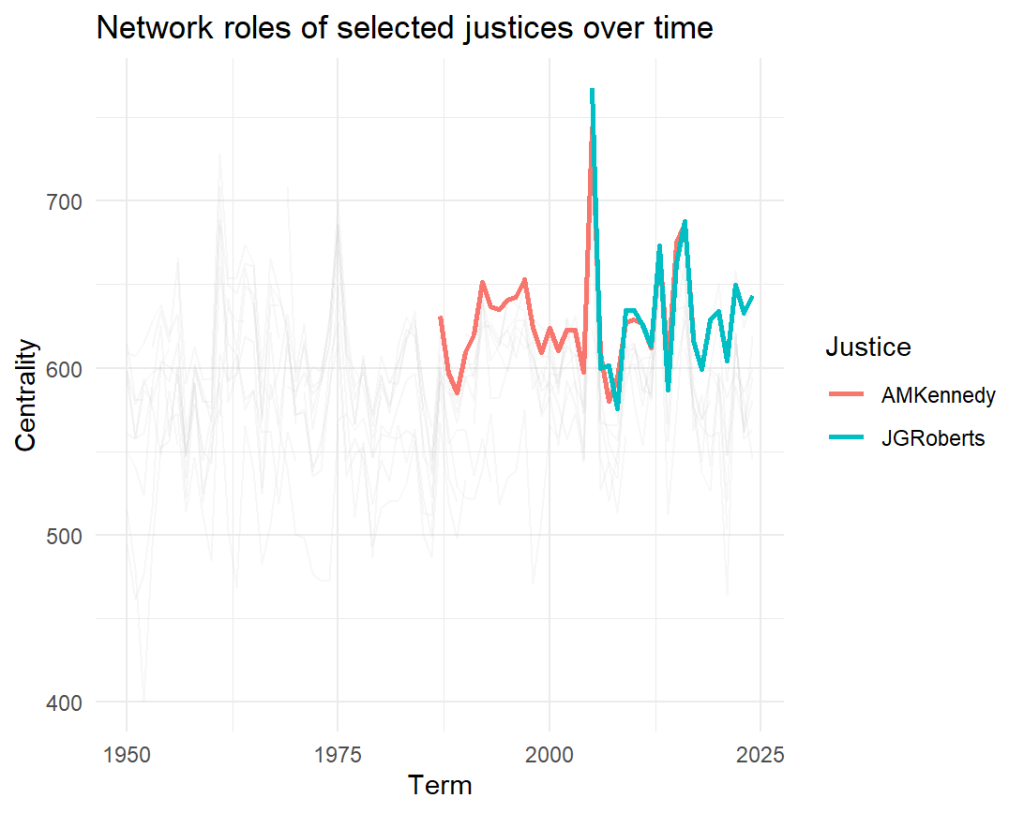

The data also reveals something else: the vanishing “bridge” or swing justice, who is not wedded to a particular ideological bloc. Justice Anthony Kennedy’s trajectory shows him as the court’s center throughout the 1990s and 2000s, maintaining higher-than-average agreement with both liberal and conservative colleagues, which made him the court’s most powerful member in close cases.

Since 1950, the most central justices have been:

- Anthony Kennedy (for 16 terms)

- William Brennan (for 13 terms)

- John Roberts (for 9 terms)

- Lewis Powell (for 6 terms)

- Sandra Day O’Connor (for 5 terms)

Kennedy is perhaps no surprise. Interestingly, Brennan also stands out here: despite his liberal voting record, the justice maintained unusually strong cross-ideological relationships with others on the court. Justices Lewis F. Powell and Sandra Day O’Connor represent this (at least recently) diminishing cohort.

Chief Justice John Roberts tells a different story. His swing-votes spiked dramatically around 2006-08, even briefly exceeding Kennedy’s peak, reflecting his early institutionalist bridge-building (such as his vote in the Affordable Care Act case). However, this centrality has declined in recent years, settling into a range typical of more consistently conservative justices. Thus, since Kennedy’s retirement in 2018, no justice has really emerged as a true swing vote.

The new normal

The comprehensive data spanning 1791 to 2025 reveals how far the court has traveled through the centuries. Where 19th-century courts featured average agreements near 95%, modern courts show an average agreement around 72%.

Since 1950, the spread between most- and least-aligned pairs has also grown. Today, the closest ideological pairs achieve near-perfect agreement while cross-ideological pairs barely reach 40%.

And the crucial swing justice may be a thing of the past: Kennedy’s 16 terms as its most central figure is not met by anyone on the current court. Meanwhile, Roberts’ brief time in this role has given way to a conservative alignment (with some outliers).

The implications are profound. If appointments can determine the court’s direction with great predictability, if justices continue to maintain stable ideological positions, and if cross-ideological alignment has reached historic lows, then each vacancy truly is a winner-take-all constitutional battle. The result is the contentious confirmation process we observe – senators voting based on expected ideology rather than mere qualifications and the court continuing to be at the center of the nation’s partisan divides.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS, Recurring Columns