Trump’s tariffs to face Supreme Court scrutiny

Updated on Oct. 31 at 8:42 a.m.

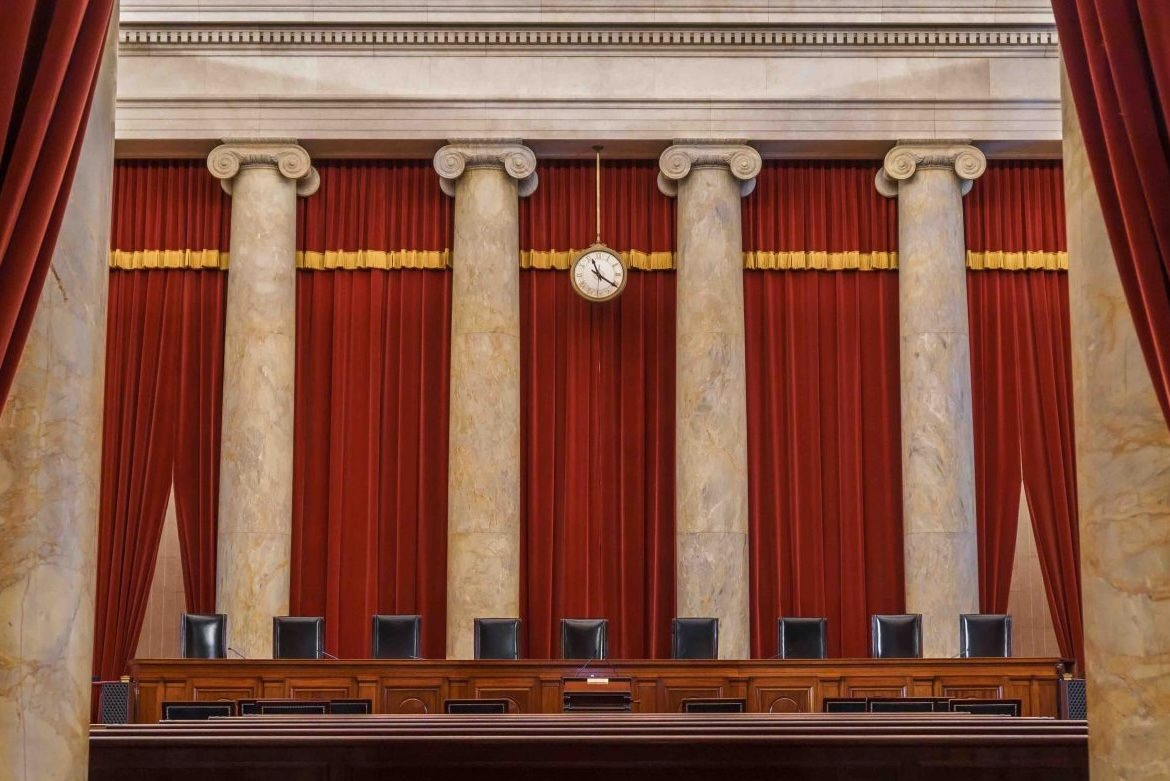

On Nov. 5, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in a pair of challenges to President Donald Trump’s power to impose sweeping tariffs on virtually all goods imported into the United States. The economic stakes are massive, but the cases are also an important test of presidential power more broadly.

Here’s a brief explainer on the issues in the cases, how they got to the court, and when the court is likely to act.

How did the dispute over the tariffs start?

Beginning in February, Trump issued a series of executive orders imposing tariffs. The tariffs can be divided into two categories. The first type, known as the “trafficking” tariffs, targeted products of Canada, Mexico, and China, because Trump says those countries have failed to do enough to stop the flow of fentanyl into the United States. The second category, known as the “worldwide” or “reciprocal” tariffs, imposed a baseline tariff of 10% on virtually all countries, and higher tariffs – anywhere from 11% to 50% – on dozens of them. In imposing the worldwide tariffs, Trump cited large trade deficits as an “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and economy of the United States.”

One case was filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia by Learning Resources and hand2mind, two small, family-owned companies that make educational toys, with much of their manufacturing taking place in Asia. To survive, the companies say, they would have to raise their prices by at least 70% to offset the highest tariffs.

Another case challenging the tariffs was brought in the U.S. Court of International Trade by several small businesses, including V.O.S. Selections, a New York wine importer, and Terry Precision Cycling, which sells women’s cycling apparel. Terry describes the tariffs as “an existential threat” to the company. It was joined with a second case, also filed in the Court of International Trade, brought by 12 states, which say that they are affected by the increased tariffs because they buy goods from overseas directly and purchase products that were imported by others.

What are the laws at the center of the dispute over the tariffs?

Article I of the Constitution gives Congress the power to “lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises,” and it requires that “Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives.”

In issuing the executive orders that imposed the tariffs, Trump relied primarily on a 1977 law, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act. Section 1701 of IEEPA provides that the president can use the law “to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States,” if he declares a national emergency “with respect to such threat.” Section 1702 of the act provides that, when there is a national emergency, the president may “regulate … importation or exportation” of “property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest.”

Has the Supreme Court addressed this question?

The Supreme Court has not weighed in on the president’s power to impose tariffs under IEEPA. United States v. Yoshida International, a 1975 decision by the U.S. Court of Customs and Patent Appeals, is perhaps most relevant to the current tariff debate because of the similarities between IEEPA and the text of the law at the center of that case, the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917.

That case began as a challenge to then-President Richard Nixon’s imposition of a 10% temporary tariff on imports in response to a large trade deficit, which in 1971 was a relatively unusual development in U.S. history. In 1974, the U.S. Customs Court – the predecessor to the Court of International Trade – ruled that Nixon did not have the power under the Trading with the Enemy Act, which allowed the president in the case of an emergency to “regulate … the importation … of … any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest.”

In response to the ruling by the Customs Court, a provision of the Trade Act of 1974 specifically gave the president the power to impose tariffs to “deal with large and serious United States balance-of-payment deficits,” but – at the same time – the law limited tariffs to a maximum of 15% and a duration of five months.

The Court of Customs and Patent Appeals reversed the decision of the Customs Court, concluding that Nixon had the authority to impose the tariffs after all. The 10% tariff, the court explained, was a “limited” one imposed “as ‘a temporary measure’ calculated to help meet a particular national emergency, which is quite different from ‘imposing whatever tariff rates he deems desirable.’”

What are the challengers’ arguments?

The challengers contend that – unlike other laws that directly deal with tariffs – IEEPA doesn’t mention tariffs or duties at all, and that no president before Trump has ever relied on IEEPA to impose tariffs. And the government has not provided an example of any other law, they add, in which Congress used the phrase “regulate” or “regulate … importation” to give the executive branch the power to tax. Indeed, the group of small businesses led by V.O.S. Selections say, “[h]undreds of statutes grant the power to regulate, and none has ever been understood to grant taxing powers. … If ‘regulate’ meant ‘tax,’ it would overturn the accepted understanding of all these laws.”

Interpreting IEEPA to give the president the power to impose unilateral worldwide tariffs would create a variety of constitutional problems, the challengers before the Federal Circuit also contend. First, they write, it would run afoul of a doctrine known as the major questions doctrine, they say, which requires Congress to be explicit when it wants to give the president the power to make decisions with vast economic and political significance. Learning Resources and hand2mind tell the justices that “Congress does not (and could not) use such vague terminology to grant the Executive virtually unconstrained taxing power of such staggering economic effect—literally trillions of dollars—shouldered by American businesses and consumers.”

Allowing the president to rely on IEEPA to impose the tariffs would also violate the nondelegation doctrine – the principle that Congress cannot delegate its power to make laws to other branches of government. In their brief, the states say that although Congress has in limited circumstances specifically given the president the power to “adjust tariff rates,” the president in this case reads IEEPA “as delegating the entirety of Congress’s tariffing authority to the President’s ‘essentially judicially unreviewable’ discretion, with no intelligible principles guiding the amount or duration of the tariffs.”

What are the government’s arguments?

The Trump administration counters that the tariffs fall squarely within the text of IEEPA. Congress’ grant of power to the president to “regulate importation,” U.S. Solicitor General D. John Sauer argues, “plainly authorizes the President to impose tariffs” because tariffs “are a traditional and commonplace way to regulate imports.”

The Federal Circuit was wrong, the Trump administration argues, when it concluded that “even if IEEPA authorizes tariffs, it does not authorize ‘unlimited’ tariffs” like the ones at the center of this case. IEEPA and another federal trade law, the National Emergencies Act, already impose substantial checks on tariffs, including by limiting “emergencies” to one year and through “a slew of procedural and reporting requirements that allow Congress to oversee and override the President’s determinations.” Nor does the “major questions” doctrine bar the president from imposing tariffs under IEEPA, Sauer writes. As an initial matter, Sauer says, the doctrine only applies when a law is ambiguous, but IEEPA clearly gives the president the power to impose tariffs through its grant of authority to the president to “regulate importation.” Moreover, Sauer continues, the Supreme Court has “never applied the doctrine in the foreign-affairs context, where Congress presumptively does grant the President broad powers to supplement his” authority under the Constitution.

How did the lower courts rule on these cases?

In the cases brought by V.O.S. Selections and the other small businesses as well as the states, the CIT on May 28 ruled for the small businesses and the states, and it set aside the tariffs. The CIT reasoned that IEEPA’s delegation of power to “regulate … importation” does not give the president unlimited tariff power. The limits that the Trade Act sets on the president’s ability to react to trade deficits, the court continued, indicates that Congress did not intend for the president to rely on broader emergency powers in IEEPA to respond to trade deficits.

The “trafficking” tariffs are also invalid, the CIT continued, because they do not “deal with an unusual and extraordinary threat,” as federal law requires. Instead, the CIT concluded, Trump’s executive order tries to create leverage to deal with the fentanyl crisis.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which hears appeals from the Court of International Trade, put the CIT’s ruling on hold while the government appealed. By a vote of 7-4, a majority of the Federal Circuit agreed that “IEEPA’s grant of presidential authority to ‘regulate’ imports does not authorize the tariffs” that Trump had imposed.

Judge Richard Taranto, an Obama appointee, wrote the dissenting opinion, which was joined by three other judges. He argued that “IEEPA’s language, as confirmed by its history, authorizes tariffs to regulate importation.” Moreover, he added, “IEEPA embodies an eyes-open congressional grant of broad emergency authority in this foreign-affairs realm, which unsurprisingly extends beyond authorities available under non-emergency laws, and Congress confirmed the understood breadth by tying IEEPA’s authority to particularly demanding procedural requirements for keeping Congress informed.”

In the case in federal court in the District of Columbia, U.S. District Judge Rudolph Contreras ruled for Learning Resources and hand2mind, agreeing with them that “the power to regulate is not the power to tax.” Contreras’ order was a narrow one, barring the government only from enforcing the tariffs against Learning Resources and hand2mind, and he put that decision on hold while the government appealed.

Who will argue next week?

The Supreme Court on Oct. 23 expanded the scheduled time for the oral argument from the normal 60 minutes to 80, although it will almost certainly last much longer than that. Three lawyers will argue: one from the Trump administration (presumably Sauer); Neal Katyal, who served as the acting solicitor general during the Obama administration, representing the small businesses; and one lawyer representing the states challenging the tariffs. Fun fact: Katyal was selected over Pratik Shah, the lawyer representing Learning Resources and hand2mind, in a coin toss.

When will the court issue its decision?

There’s no way to know how long it will take. On one hand, the case is a complicated one and could involve multiple opinions – not only a majority opinion but perhaps also dissents and concurring opinions, all of which could slow down the process of finalizing and releasing the opinion. On the other hand, the Trump administration urged the justices to act quickly, telling them that “‘[t]he longer a final ruling is delayed, the greater the risk of economic disruption,’” and the court fast-tracked the case on the schedule that the government proposed, which at least suggests that the court is prepared to act expeditiously.

Posted in Court News, Merits Cases

Cases: Learning Resources, Inc. v. Trump (Tariffs)