Ranking the modern chief justices

Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

On Monday, Oct. 6, the first day of the Supreme Court’s 2025-26 term, as well as the 20th anniversary of Chief Justice John Roberts’ tenure, it felt appropriate to ask: Who actually runs the Supreme Court?

Former Justice Felix Frankfurter insisted the answer was “no one.” “Aside from the power to assign the writing of opinions … a Chief Justice has no authority that any other member of the Court hasn’t … The Chief Justice is primus inter pares [first among equals]. He presides … in Court and at conference.”

That’s the civics-book truth: nine life-tenured judges, each a sovereign vote, no formal boss. Former Chief Justice William Rehnquist, the chief prior to John Roberts, said much the same: the chief’s vote “carries no more weight” than that of any other justice, and any hope that a skillful administrator will “bring the Court together” is mostly fantasy. According to Rehnquist, the chief presides over eight “associates … as independent as hogs on ice. He may at most persuade or cajole them.”

Yet persuasion and cajoling matter – especially in a world where the person in the middle can, if in the majority, decide who writes the opinion that everyone else must sign. That is where the office becomes something more than a ceremonial gavel. As my friend Dan Cotter puts it in his book “The Chief Justices,” a successful chief “has the ability to be a superior among his equals,” using the job’s quiet levers to shape the court’s image and legacy. The levers aren’t hidden: preside at conference, frame the questions, assign the majority when in the majority, and – at critical moments – pick up the pen.

This article takes Frankfurter and Rehnquist’s caution seriously and tests Cotter’s claim with data. Using the Supreme Court Database, it tracks three things you can actually observe across the five modern chief-justice eras – Fred Vinson, Earl Warren, Warren Burger, Rehnquist, Roberts: (1) whether the court speaks with one voice (consensus); (2) how the chief manages close cases (leadership); and (3) how often doctrine truly moves (impact).

Consensus

Unanimity is the clearest way to see real agreement on the Supreme Court because it collapses the two things that usually get pulled apart – outcome and reasoning – into a single signal. When every justice signs onto the judgment and the opinion, the court isn’t just announcing who won; it is speaking with a common legal voice about why. That gives lawyers and lower courts a rule they can follow without guessing which concurrence controls or how to add up fractured rationales.

Unanimity also carries legitimacy. A unified court looks less like a set of camps and more like an institution delivering a rule of decision. Unanimity is also simple to measure and compare across eras. It is the most conservative test of consensus: If the court can get all the way to a high level of consensus, that is a qualitatively different kind of agreement than a bare majority or a fractured alignment.

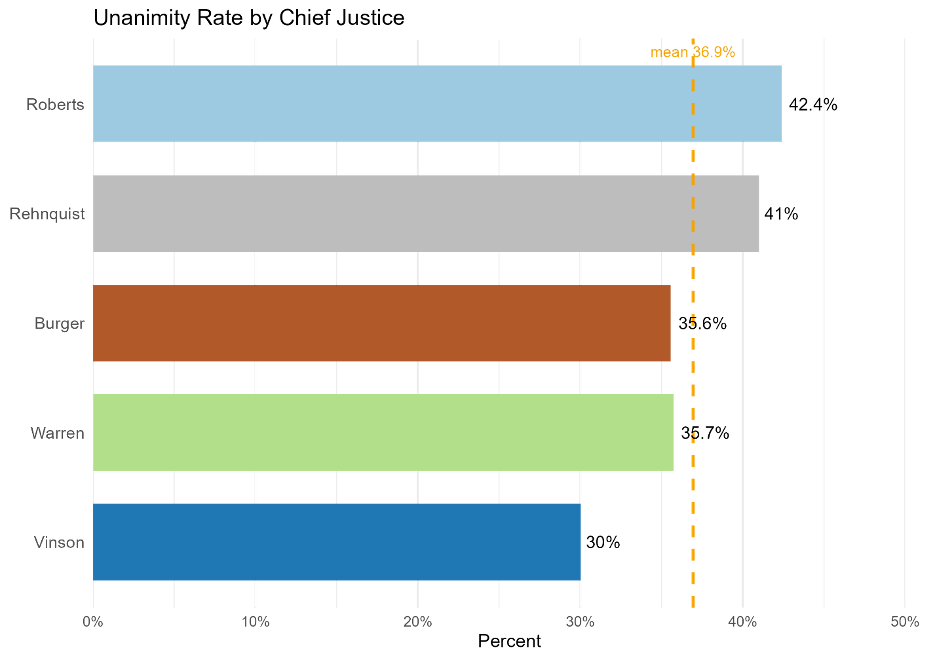

As the chart illustrates, unanimous rulings have become more common over time. Under Vinson, roughly three in 10 decisions were unanimous; that share climbed in the Warren and Burger Courts to the mid-thirties, reached about 41% under Rehnquist, and sits at roughly 42% in the Roberts era. Read plainly, that is a steady drift toward more agreement over time.

None of this means the cases are small. A unanimous decision can reset national practice just as surely as a 5–4 decision can. What it does mean is that the court often prefers to settle conflict with as much buy-in as possible, even if that means deciding less than the parties asked for. The picture that emerges across chiefs is consistent: a court that still divides on plenty of high-profile issues, but that also, with growing frequency, finds common ground to resolve the law.

Leadership

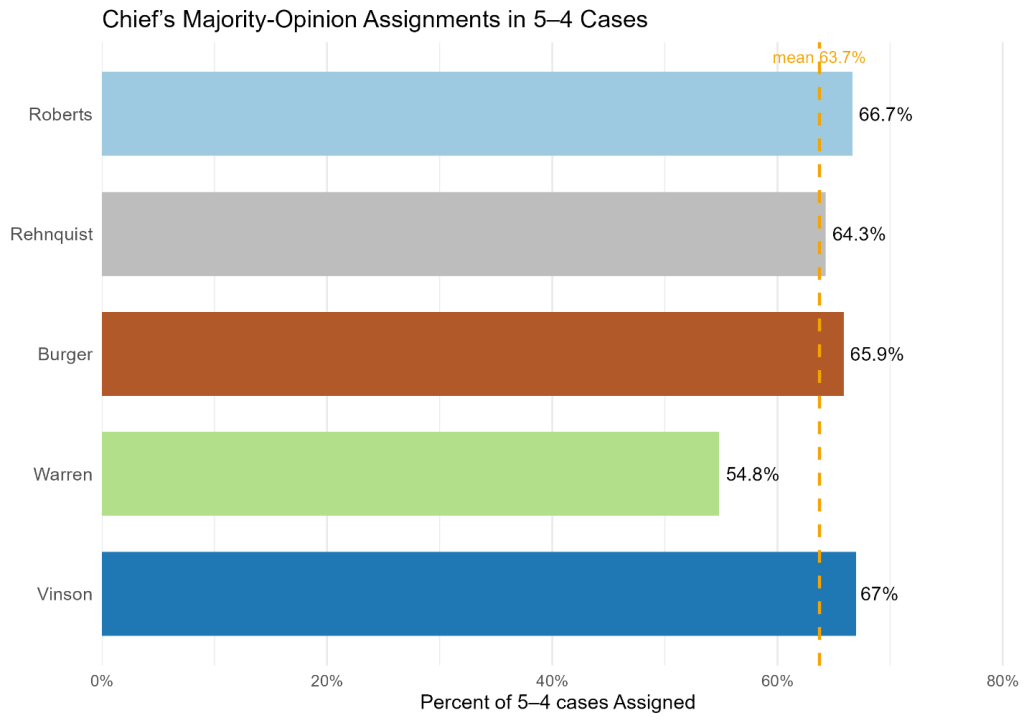

By custom, the chief assigns the opinion when in the majority. This graph shows how often, in 5–4 cases, the assignment came from the chief, or put another way, the frequency with which the chief was in the majority in these cases.

Chiefs tend to keep a large share of 5–4 assignments: Vinson 67%, Warren 54.8%, Burger 65.9%, Rehnquist 64.3%, Roberts 66.7% (among cases with a known assigner). That pattern suggests strong central steering in the closest cases, with Warren the outlier on the low side and the others clustered around two-thirds.

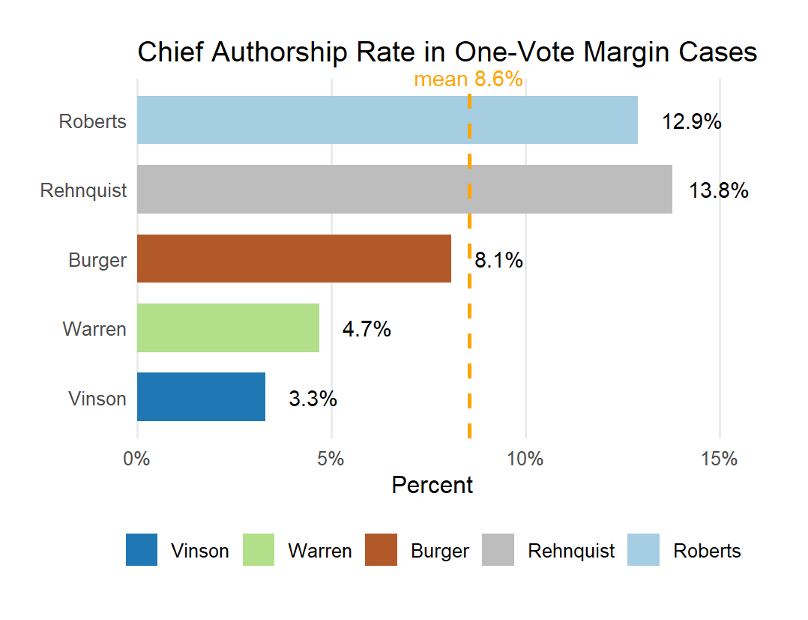

The next graph focuses on the chief’s authorship rate in one-vote cases. These are managerial choices. Place the opinion with the right author and you keep your fifth vote; take the pen yourself and you can dictate the language with the acceptance of the majority coalition.

Rehnquist and Roberts both show assertive assignment in 5–4s by authoring a meaningful share of those one-vote decisions. That is what control looks like when vote splits are close: you don’t win every divided case, but you shape the ones you win. Put another way, Rehnquist and then Roberts were the justices most able to not only command 5-4 majorities, but to author the opinions while holding together coalitions in often the most consequential and coveted authorship decisions.

Impact

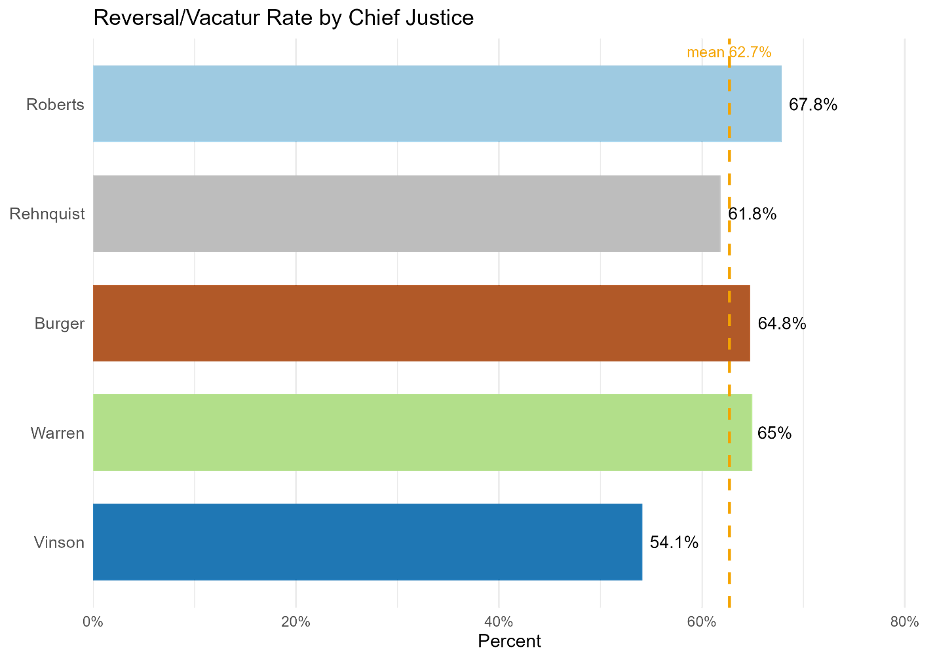

Impact can be seen as a measure of change. This underlies the theory of aggressive grants and why the justices reverse decisions more often than they are overturned. The notion of impact as related to change does not relate to any normative claims on my part about the benefits of impact but does signal legal change made by the court.

Looking across the last five chief justices, the Supreme Court usually overturns the lower court in the cases it decides: about 54% of the time under Vinson, 65% under Warren, 65% under Burger, 62% under Rehnquist, and about 68% under Roberts – roughly two out of three decisions today. By contrast, overruling precedent is rare in every era and remarkably steady, sitting around 2–3% of decisions (about 1.7% under Vinson, 2.6% Warren, 2.3% Burger, 2.4% Rehnquist, 2.2% Roberts). In short: frequent reversals of lower courts but very few outright changes to the court’s own past decisions.

An index

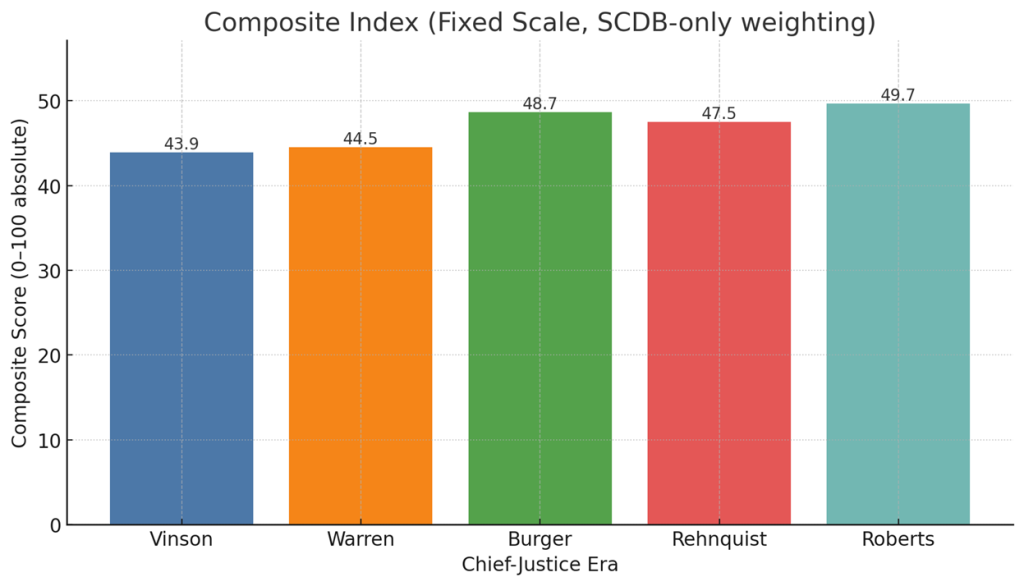

Based on the above, I constructed the composite scores below from the coding in the Supreme Court Database (more methodological details are available at Legalytics).

- Consensus: Share of unanimous decisions

- Leadership: Rate of when the chief was in the majority in divided cases, assignment rate (all cases), assignment rate in 5–4 decisions, and authorship in one-vote cases

- Impact: Precedent alteration and reversal of the lower court decisions

The bars report each chief-justice era’s composite score. On this scale, Roberts sits at the top of the group, followed closely by Burger and Rehnquist, with Warren and Vinson a bit lower.

A lasting picture

The Guardian recently quoted former judge and Roberts friend J. Michael Luttig: “John Roberts knows exactly what he is doing … and he knows exactly the message he is sending to America.” The piece describes a chief with disciplined self-awareness who cares deeply about the court’s public image. His attention to detail is legendary; he rehearses questions and even fine-tunes jokes before argument. “He speaks so smoothly – and disguises his inner convictions so thoroughly – that he has been able to straddle political and personal divides.” That public craft matches the managerial traces the data leave behind on his 20th anniversary on the bench: a chief who values consensus, chooses his moments to take the pen, and keeps the institution’s voice steady even when the docket’s edges are sharp.

That managerial profile is exactly what the composite index is designed to detect. Roberts tops it not because he is the most transformative – Warren’s era still registers the largest formal doctrinal shifts – but because he combines the highest unanimity with targeted control of close cases. He is frequently in the majority when the court divides, he assigns strategically in 5–4 cases, and he authors when it preserves the coalition.

But what about the bigger picture? Frankfurter and Rehnquist were right about the limits: the chief is one vote, not a boss. But Cotter’s “superior among equals” is visible in the traces a chief leaves behind – how often the court speaks with one voice, who authors when the case is close, and whether doctrine actually moves. As described, those are managerial choices, and they vary across eras in ways the figures make plain: Warren as architect of change, Rehnquist as manager of close cases, Roberts as coalition-builder with a steady hand on assignments.

Of course, none of this resolves the normative fights about outcomes. But it does give us a fair, repeatable way to judge how each chief used the office – how persuasion, not command, became decisions that lower courts must follow. If first among equals means anything at the Supreme Court, that is where it resides.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS, Recurring Columns