Do state limits on malpractice actions apply in federal court?

Berk v. Choy, to be argued on Oct. 6, surely will be the Supreme Court case of the year for medical professionals. At issue in the case is the extent to which a set of common state statutes designed to stem medical malpractice litigation apply in federal court. If they don’t apply in federal court, victims who have a way to get into federal court will have a much easier time pursuing litigation against doctors than those who cannot.

The case involves Delaware’s “affidavit of merit” statute, something that dozens of states have passed in recent years. Although the details vary, the key concept is that for a medical malpractice action to proceed, the case either has to involve medical negligence that is pretty obvious – the doctor left a foreign object in the patient’s body, the doctor operated on the wrong person, the doctor operated on the wrong organ – or the plaintiff has to file with the complaint an affidavit from a medical professional attesting to the negligence of the doctor who is being sued. Because those affidavits are somewhat hard to come by – how many doctors want to help someone sue another doctor for malpractice? – they pose a serious obstacle to the pursuit of many medical malpractice claims.

The case before the Supreme Court arose from a claim by Harold Berk that a doctor (Wilson Choy) and the hospital where he was treated (Beebe Medical Center) were negligent in treating an ankle and foot injury that Berk sustained at a house he owns in Delaware. If he had filed suit in a Delaware state court, the court would have dismissed the action immediately, because he does not have an affidavit from a doctor stating that Choy and Beebe were negligent. Because Berk is a resident of Florida, however, the parties are diverse – that is, from two different states – and federal law therefore gives him the option to bring his case in federal court rather than state court.

The first question for the federal court in deciding whether to apply the affidavit of merit statute is if it should follow federal procedures for civil cases or instead should follow the more onerous procedures that would apply in a Delaware state court. Typically, federal courts answer those questions under the “Erie” doctrine, referring to a famous 1938 case in which the Supreme Court held that federal courts should follow the substantive law that states create to govern conduct within their borders but should follow the procedural rules that Congress and the Supreme Court create to govern cases in federal courts.

In this case, the lower courts dismissed Berk’s case on the theory that the affidavit of merit statute is “substantive” for purposes of the Erie doctrine. Because many other courts have refused to apply those statutes in federal court, it seemed like a likely case for Supreme Court attention – and so we have oral arguments on the question next week.

Berk argues that federal courts shouldn’t apply affidavit of merit statutes because they “answer the same question” as the applicable federal rules. From his perspective, the federal rules (principally Rules 8 and 9 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure) define all of the requirements for getting a case heard in federal court. Those rules require only a short statement of the basis of the complaint and say nothing about anything like an affidavit of merit. Other rules discuss the circumstances that might require “verification” of a complaint or disclosure of expert testimony, but the requirements of the Delaware statute are quite different from what those rules contemplate.

Choy and Beebe, by contrast, make two main points, one textual and one more atmospheric. The textual point provides an argument that nothing in the Delaware statute directly conflicts with the federal rules. It centers on the statement in Rule 11 that there can be no requirement of an affidavit or other verification “[u]nless a rule or statute specifically states otherwise.” Because the Delaware statute in this case does specifically state otherwise, there is no conflict with the federal rules in applying the statute.

More generally, Choy and Beebe portray the statutory requirements as falling outside of anything that the federal rules discuss. The affidavit requirement is not, they say, a pleading, but simply an additional requirement that Delaware (and many other states) impose in these kinds of cases. There are many reasons why federal courts dismiss cases that do not appear in the rules themselves, and the Delaware statute provides just one more.

The more atmospheric point is the real-world purpose of these statutes, which is to provide a major substantive limitation on the ease with which medical malpractice claims can be brought. As Choy and Beebe explain (joined by filings from the American Medical Association and the large group of states that have these statutes), the costs of malpractice litigation are a substantial share of health care costs in the United States, and those costs do not to any major degree go to benefit those who were injured by negligent medical practice.

For my part, not surprisingly, I am impressed by an amicus (“friend of the court”) brief from a prestigious group of professors who study civil procedure. They work through the details of all that would be required to implement the affidavit of merit statutes in federal court and argue that the intrusion into routine federal judicial administration would be chaotic. For them, the basic problem is that Delaware (and the other states) was unwilling to change the substantive rules for malpractice actions, so they instead have changed the procedural rules. The choice to go with procedure, the professors say, means that the changes should not apply in federal court.

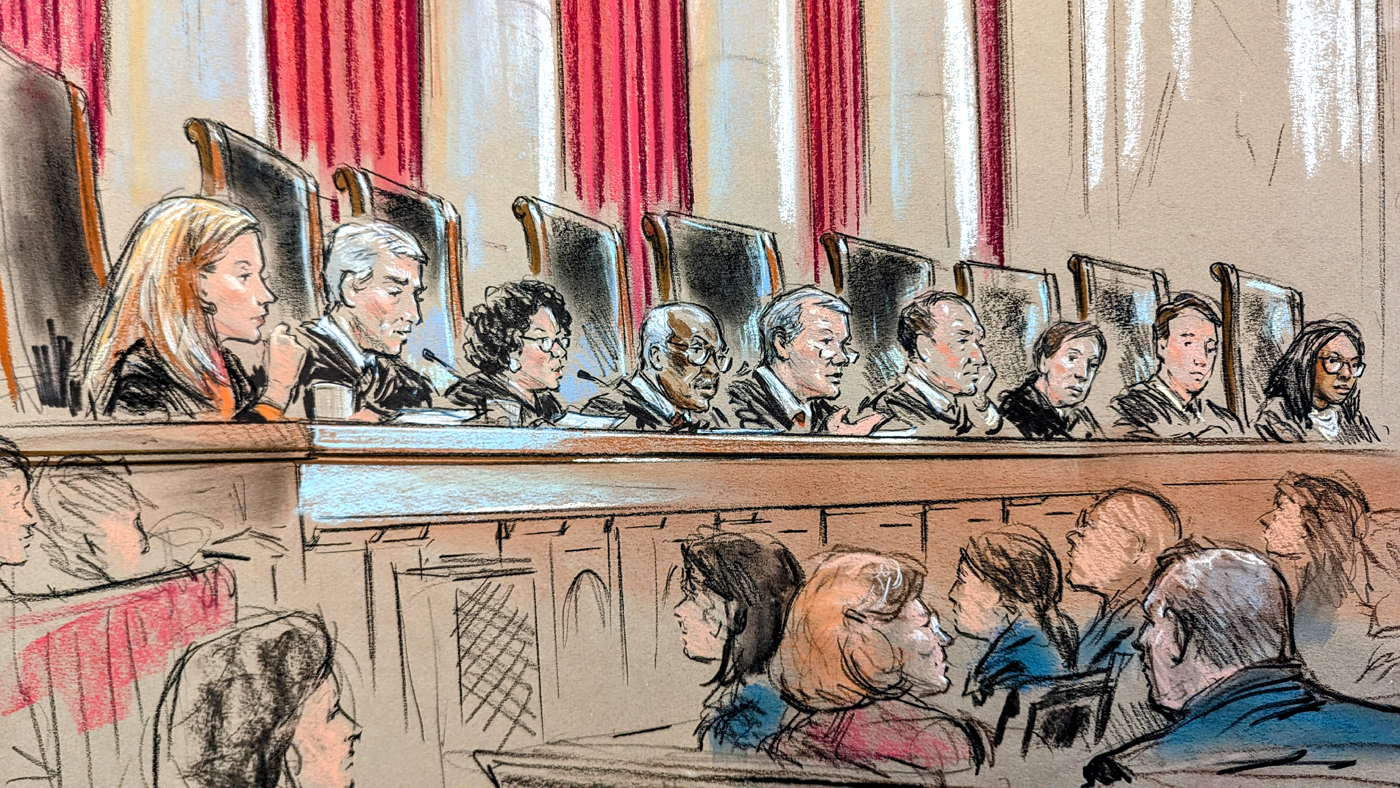

I expect a lively argument. The bench has expertise in civil procedure (Justice Elena Kagan, a former professor), lengthy experience as a trial judge (Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson), and a broad sensitivity to the problematic costs of this kind of litigation. I will be surprised if several of the justices are not sympathetic to the desire of the states to quell this kind of litigation, but whether most of the justices will share that concern is less clear.

Posted in Court News, Merits Cases

Cases: Berk v. Choy