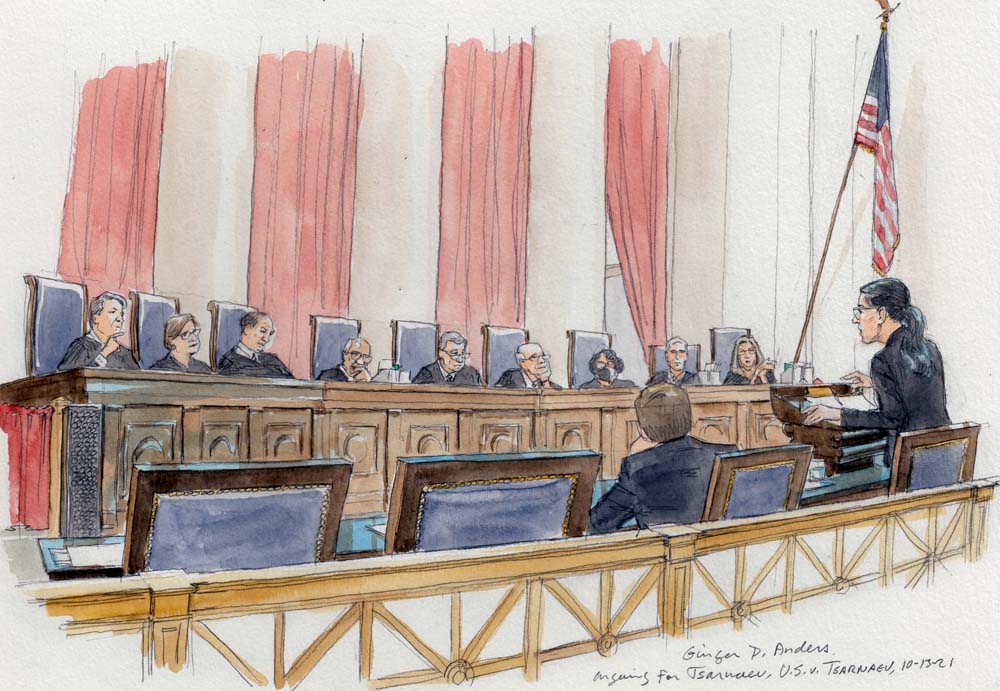

Argument analysis

Justices appear to favor reinstating death penalty for Boston Marathon bomber

on Oct 13, 2021 at 3:32 pm

The Supreme Court heard oral argument on Wednesday in the case of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who was convicted for his role in the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, which killed three people and badly injured hundreds more. A jury sentenced Tsarnaev to death, but a federal appeals court threw out Tsarnaev’s death sentences last year. That prompted the federal government to come to the Supreme Court, asking the justices to reinstate the death penalty for Tsarnaev. After over 90 minutes of oral argument, a majority of the justices seemed inclined to do just that.

The ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit rested on two different rationales. First, the court of appeals concluded, the trial judge should have asked would-be jurors what media coverage they had seen or heard about Tsarnaev’s case. Second, the 1st Circuit held, the trial judge should have allowed Tsarnaev’s lawyers to introduce evidence that Tsarnaev’s brother, Tamerlan, was involved in a separate, unsolved triple murder two years before the bombings.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.

Wednesday’s oral argument focused primarily on the second issue in the case – whether the judge was wrong to exclude evidence of the 2011 triple murder. Representing Tsarnaev, lawyer Ginger Anders told the justices that Tsarnaev’s defense at his sentencing rested on the theory that his older brother had “indoctrinated” him and was more likely to have been the leader in the bombings, making Dzhokhar Tsarnaev less responsible and therefore less deserving of the death penalty. The 2011 murders, Anders explained, demonstrated Tamerlan’s commitment to “violent jihad,” but the exclusion of that evidence “distorted the entire penalty proceeding.” By contrast, Anders continued, allowing Tsarnaev to tell the jury about the 2011 murders “would have changed the terms of the debate.”

Several justices were skeptical, however, that the trial judge was wrong to exclude the evidence. Chief Justice John Roberts suggested that introducing the evidence would have turned attention to something that could not be resolved – who committed the 2011 murders in the first place. And it wasn’t a question of whether the jury should believe that Tamerlan or a friend of his, Ibragim Todashev, was ultimately responsible for the 2011 murders, Roberts observed, because both of them are dead and could not testify.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett echoed this idea. Regardless of whether the evidence is reliable, she told Anders, the trial judge simply concluded that the evidence would confuse the jury and would not, by contrast, add too much.

Justice Neil Gorsuch spoke up a few minutes later. If the judge thought, he said to Anders, that your theory was that the evidence supported Tamerlan’s leadership of the bombings, but there was no way to know who took the lead in the 2011 murders, what’s wrong with excluding the evidence?

Justice Samuel Alito protested that allowing the evidence of the 2011 murders to be introduced could create a “trial within a trial” about what happened, as the government would want to introduce evidence to counter the narrative that Tamerlan had played a leading role in those murders.

Anders pushed back on two fronts. First, she disputed the idea that allowing evidence of the 2011 murders would lead to an “improper mini-trial.” “It’s the trial,” she stressed – the center of Tsarnaev’s efforts to ward off the death penalty. Second, she added, there is no need to resolve all of the details regarding who did what with regard to the 2011 murders. Other forms of hearsay were introduced in this same case, she noted, and the jury was allowed to evaluate their significance.

Eric Feigin argues for the federal government. (Art Lien)

Justice Elena Kagan saw things differently than some of her more conservative colleagues. She told Deputy Solicitor General Eric Feigin, who represented the United States, that the federal government’s case rests on the idea that the evidence of Tamerlan’s involvement in the 2011 murders wasn’t strong enough. But, Kagan queried, is that really the trial judge’s decision to make? Isn’t it enough that the evidence is related to Tsarnaev’s theory of why he is less culpable, Kagan continued, isn’t it the jury’s job to decide whether the evidence is sufficiently reliable? Kagan observed that the trial judge had allowed other evidence that showed what kind of person Tamerlan was – evidence, for example, about Tamerlan poking people and shouting at people.

Justice Stephen Breyer followed up on Kagan’s questions. He pressed Feigin to explain why, if an affidavit from Todashev was sufficiently reliable for law enforcement officials to use it as part of an application for a warrant to search a car, it couldn’t be introduced in Tsarnaev’s defense in his capital case.

The justices spent less time on the 1st Circuit’s holding that the district court should have asked would-be jurors specific questions about what media coverage they had seen about the case. Justice Clarence Thomas asked Feigin what test the Supreme Court should use to review the 1st Circuit’s ruling. Should the justices look at whether the court of appeals went beyond its power to supervise the trial court, Thomas inquired, or should it instead simply consider whether the 1st Circuit’s ruling was reasonable?

Feigin responded that the court could use either approach, but he cautioned that a rule that was as “wooden” and “rigid” as the one that the 1st Circuit applied in this case would be unreasonable.

Judge George O’Toole, who presided over the Tsarnaev trial, questions a prospective juror in 2015. (Art Lien)

Justice Sonia Sotomayor countered that the 1st Circuit’s rule “wasn’t all that rigid.” The trial judge had not allowed lawyers to question jurors about what kind of publicity they had seen, she stressed, even though “there was a whole lot of different publicity here.” “That seems like an extreme control over trying to figure out whether someone could have been influenced by that publicity,” she concluded.

In the last few minutes of Feigin’s initial turn at the podium, Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked the question that many people were likely wondering about. “What,” she queried, “is the government’s end game” in Tsarnaev’s case? On the one hand, Barrett observed, earlier this year Attorney General Merrick Garland imposed a moratorium on federal executions, but on the other hand, the federal government is asking the justices to reinstate the death penalty for Tsarnaev.

The jury, Feigin emphasized, imposed a “sound verdict,” and the court of appeals was wrong to reverse it. The Supreme Court should allow the jury’s verdict to be carried out. At a minimum, Feigin noted, the “easiest way to resolve” the case is to conclude that the jury would have reached the same verdict even if the judge had asked jurors about pretrial publicity and had allowed Tsarnaev to introduce his additional evidence. Feigin urged the justices to “think about what the jury actually heard,” and then recounted the events around the bombing in a lengthy monologue that seemed more like an opening statement at a trial than a Supreme Court rebuttal. The jury’s verdict in Tsarnaev’s case, he concluded, “was based on that evidence, not anything about pretrial publicity or anything about” the 2011 murders.

A decision in the case is expected sometime next year.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.