Statistics

On a new, conservative court, Kavanaugh sits at the center

on May 13, 2021 at 11:59 am

The Supreme Court has issued opinions in roughly half of the cases it will decide this term, and so far Justice Brett Kavanaugh has emerged as the new “median justice” on a solidly conservative court. If the trend holds, Kavanaugh will supplant Chief Justice John Roberts, who occupied the court’s ideological center before the rightward shift caused by the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her quick replacement by Justice Amy Coney Barrett last fall.

Kavanaugh’s position, as well as a number of other initial trends outlined below, are based on data from the 31 merits opinions the court has handed down so far in the 2020-21 term. The dataset consists of all opinions issued in argued cases, two unsigned opinions granting emergency relief on the shadow docket, and several “summary reversals” (unsigned opinions in which the court granted a petition for review and reversed a lower court without hearing oral argument). The dataset excludes one case that was dismissed as “improvidently granted” and a host of shadow-docket rulings that lacked a formal merits opinion.

The court is expected to issue an additional 33 opinions this term, including in hotly contested cases involving the Affordable Care Act, access to the ballot, and a clash between religious freedom and LGBTQ rights. The trends we identify here could shift by the end of June. (As always, we will publish a comprehensive Stat Pack with detailed final statistics at the end of the term.) But the data below present a preliminary picture of the court’s decision-making in the first year of the new six-justice conservative majority.

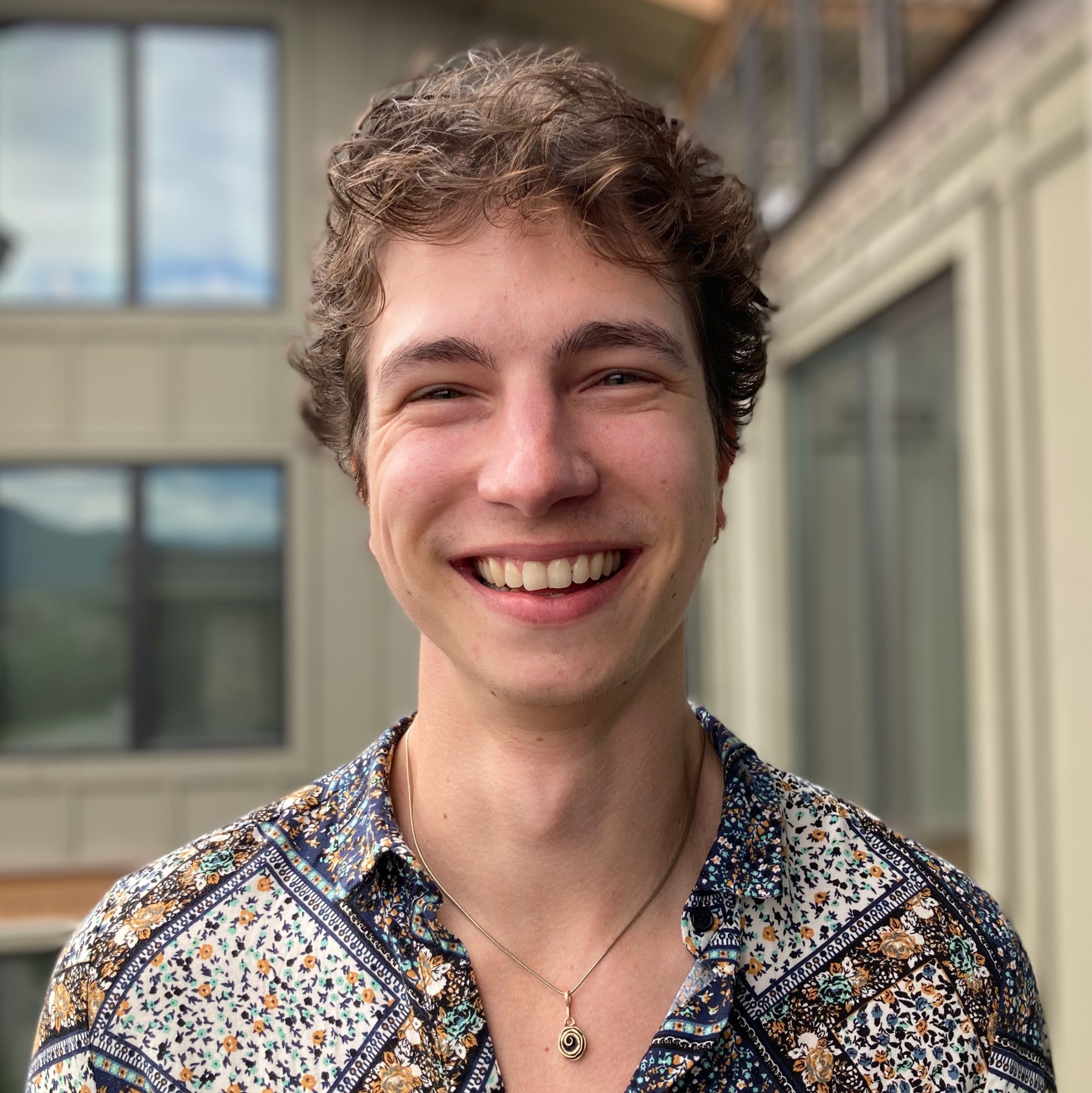

Last term, the universally agreed upon story was Roberts’ 97% frequency in the majority of decided cases. The chief was commonly presented as the court’s median justice, exerting considerable influence in closely divided cases as the member of the conservative wing most willing to vote with the liberal justices. The court’s balance shifted, however, after Ginsburg’s death and Barrett’s confirmation.

Majority frequency seems to be the story again so far this term, but this time, it is Kavanaugh who sits at the court’s nexus. He is currently matching Roberts’ 97% frequency in the majority from last term, whereas Roberts’ percentage in the majority has dropped to 87%. Kavanaugh has cast key votes in a number of closely contested cases this term – most notably in two rulings on the shadow docket striking down COVID-19 restrictions on religious worship (both of which prompted Roberts to dissent). Kavanaugh also joined with the other conservatives (this time including Roberts) and wrote the majority opinion in a case on the constitutionality of sentencing juveniles to life without parole, and he (along with Roberts) sided with the three liberals in a ruling about what constitutes a “seizure” under the 4th Amendment.

In a sign of President Donald Trump’s deep imprint on the court, all three Trump appointees – Kavanaugh, Barrett and Justice Neil Gorsuch – have been in the majority more often than any other justice this term. And it’s no surprise that the justices in the majority least often are the only three members of the court appointed by Democratic presidents: Justices Elena Kagan, Stephen Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor. Each of them, however, has been in the majority in over two-thirds of the court’s cases this term – proof that many decisions are not divided along ideological lines.

Ideological alignment is evident when examining the justices’ agreement with one another. The chart above shows the six pairs of justices with the highest rates of voting together and the six pairs of justices with the lowest rates of agreement. Three of the top six pairs include Barrett – so far she has voted alongside both Gorsuch and Justice Clarence Thomas in every case that she has participated in, and she has agreed with Justice Samuel Alito 95% of the time. (Barrett’s sample size, however, is smaller than the other justices. Of the 31 cases in our dataset, she did not participate in 10 that were argued before she joined the bench and two others that were decided without argument just after her appointment.)

The liberal justices display similar agreement: Breyer has voted with Sotomayor and Kagan 97% of the time, and Sotomayor and Kagan have voted together 94% of the time. The pairs in least agreement, on the other hand, consist of justices who are least ideologically aligned.

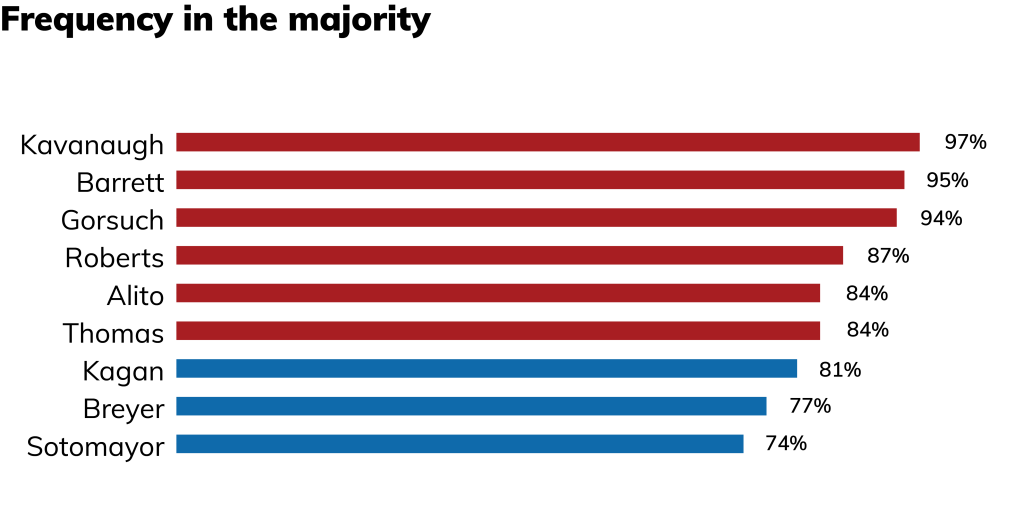

Breaking down the decided cases by vote split, we see two trends borne out. First, over half of the decisions so far were reached by unanimous vote. That’s slightly above the 48% average over the past decade (though unanimity often decreases toward the end of the term because divided decisions take longer to release). The justices often emphasize the court’s tendency to decide cases unanimously when they are asked about perceptions that the court is divided along partisan lines.

Breaking down the decided cases by vote split, we see two trends borne out. First, over half of the decisions so far were reached by unanimous vote. That’s slightly above the 48% average over the past decade (though unanimity often decreases toward the end of the term because divided decisions take longer to release). The justices often emphasize the court’s tendency to decide cases unanimously when they are asked about perceptions that the court is divided along partisan lines.

Still, non-unanimous cases are likely to be closely divided (i.e., decided by either a 6-3 or 5-4 vote) and are likely to result in conservative outcomes. We define a case as having a conservative outcome if the majority consists entirely of Republican-appointed justices, and we define a case as having a liberal outcome if the majority consists of all three Democratic-appointed justices joined by two or three crossover votes from Republican appointees. (So far this term, no closely divided case has split the three Democratic-appointed justices – either all three of have been in the majority or, more commonly, all three have been in dissent.)

Although the breakdown of close cases with partisan outcomes has varied widely under the Roberts court, the majority of close decisions since 2018 when Kavanaugh replaced Justice Anthony Kennedy (long-regarded as the court’s “swing vote”) have had a conservative outcome. This term, a number of major rulings, from the life-without-parole and COVID-19 cases mentioned previously, to the government’s efforts to exclude people living in the country without authorization from the 2020 census or curtail relief from deportation for a minor crime, have been handed down by a conservative majority with all three liberal justices in dissent.

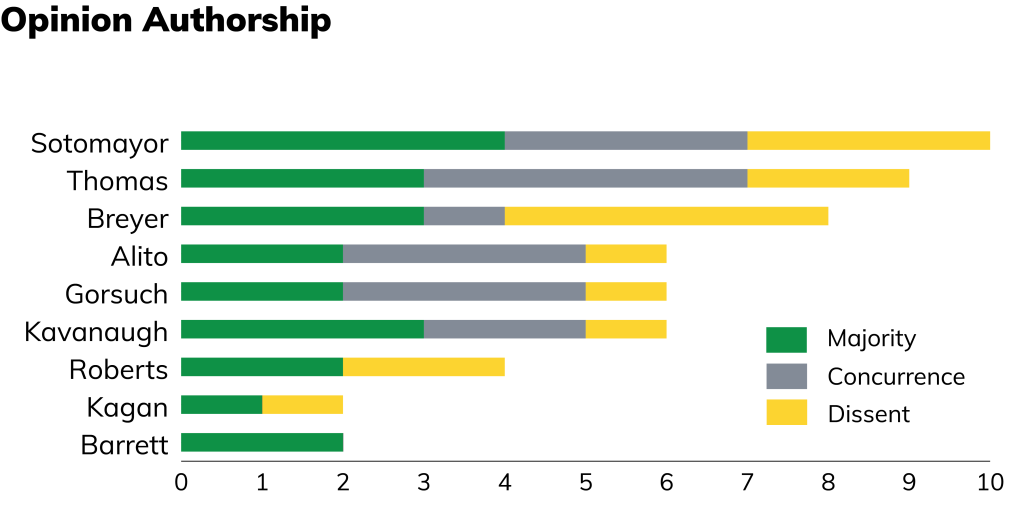

A final measure examined at this point in the term is the number of opinions authored by each justice. As in past terms, Roberts and Kagan have authored the fewest total opinions. Both rarely write concurring opinions, and when they are in dissent, they often will join a dissenting opinion written by another justice rather than write one themselves. (Of Roberts’ two dissenting opinions so far this term, one was a lone dissent in a case about student speech that struck at the heart of what damages plaintiffs must claim to bring a lawsuit for violation of a constitutional right in federal court. It was the first time the chief has been the lone dissenter in an 8-1 case since he joined the bench in 2005.)

Sotomayor and Thomas, on the other hand, are the court’s most prolific authors of concurring opinions and are similarly inclined to author dissents. As usual, they are on the high end of number of opinions written so far. Breyer has written a large number of dissenting opinions as well. He is generally a frequent dissenter (Ginsburg was the liberal justice more “notorious” for her dissents, though this was generally due to their linguistic force as opposed to their sheer number), and this term Breyer has penned a majority of the liberal justices’ dissenting opinions in cases decided 6-3 along ideological lines.