Empirical SCOTUS: Precedent: Which justices practice what they preach

on Jul 7, 2020 at 2:35 pm

Although Supreme Court justices are by no means bound by their past decisions, they often respect them, for a variety of reasons. Justice Elena Kagan offered her reasons for remaining faithful to precedent in her dissent from last term’s decision in Knick v. Township of Scott, which overturned the court’s precedent on the issue of eminent domain in the state law context in Williamson County Regional Planning Comm’n v. Hamilton Bank of Johnson City:

“[I]t promotes the evenhanded, predictable, and consistent development of legal principles, fosters reliance on judicial decisions, and contributes to the actual and perceived integrity of the judicial process.” … Stare decisis, of course, is “not an inexorable command.” … But it is not enough that five Justices believe a precedent wrong. Reversing course demands a “special justification—over and above the belief that the precedent was wrongly decided.”

This respect does not mean that the court doesn’t regularly strike down its past decisions. The court has reversed at least one of its past decisions in every term of the Roberts Court and, per the Supreme Court Database, has overturned at least three past decisions a term on average since 1946.

In a prominent 1996 article, Professors Jeffrey Segal and Harold Spaeth wrote (paywall link) about how justices who dissent in important cases continue to dissent in future cases on the same issues, even as precedent clearly builds in the opposite direction (as in the case of a justice who dissented from Roe v. Wade and then continued to dissent from subsequent decisions that revisited the question of a constitutional right to an abortion). They described this as a test of the strength of stare decisis, or adherence to precedent, as a constraint on Supreme Court decision-making. Their evidence was overwhelming. Of the 15 justices’ decisions they analyzed, no justice voted in favor of precedent over their past dissenting direction more than a third of the time.

The seeming rigidity with which justices hold to their past dissents in an area of law makes Chief Justice John Roberts’ concurrence in June Medical Services v. Russo — in which he voted to adhere to Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, in which he had dissented, out of concern about stare decisis — that much more surprising. In his concurrence in June Medical, Roberts wrote:

I joined the dissent in Whole Woman’s Health and continue to believe that the case was wrongly decided. The question today however is not whether Whole Woman’s Health was right or wrong, but whether to adhere to it in deciding the present case … The legal doctrine of stare decisis requires us, absent special circumstances, to treat like cases alike. The Louisiana law imposes a burden on access to abortion just as severe as that imposed by the Texas law, for the same reasons.

In another decision this term, Kagan surprised many by joining Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito in dissent in Ramos v. Louisiana, likely for the sake of voting to uphold the precedent that was overturned as a result of the decision. Alito’s dissent began: “The doctrine of stare decisis gets rough treatment in today’s decision. Lowering the bar for overruling our precedents, a badly fractured majority casts aside an important and long-established decision with little regard for the enormous reliance the decision has engendered.”

Recently, Professor William Baude wrote an article that, while not arguing for strong adherence to stare decisis, describes the necessity of a theory of precedent to dictate when cases should be overruled. Baude cited Justice Clarence Thomas’ concurrence in last term’s Gamble v. United States, which discussed reasons for a less strict adherence to the court’s past decisions, as an example of a theory deserving of addition scholarly and legal scrutiny.

Thomas wrote in Gamble:

In my view, the Court’s typical formulation of the stare decisis standard does not comport with our judicial duty under Article III because it elevates demonstrably erroneous decisions—meaning decisions outside the realm of permissible interpretation—over the text of the Constitution and other duly enacted federal law. It is always “tempting for judges to confuse our own preferences with the requirements of the law,” … and the Court’s stare decisis doctrine exacerbates that temptation by giving the veneer of respectability to our continued application of demonstrably incorrect precedents.

In a somewhat similar vein, Justice Antonin Scalia, dissenting in Lawrence v. Texas, the decision that overturned the court’s precedent upholding a state law banning sodomy in the privacy of one’s own home, wrote, “I do not myself believe in rigid adherence to stare decisis in constitutional cases; but I do believe that we should be consistent rather than manipulative in invoking the doctrine.”

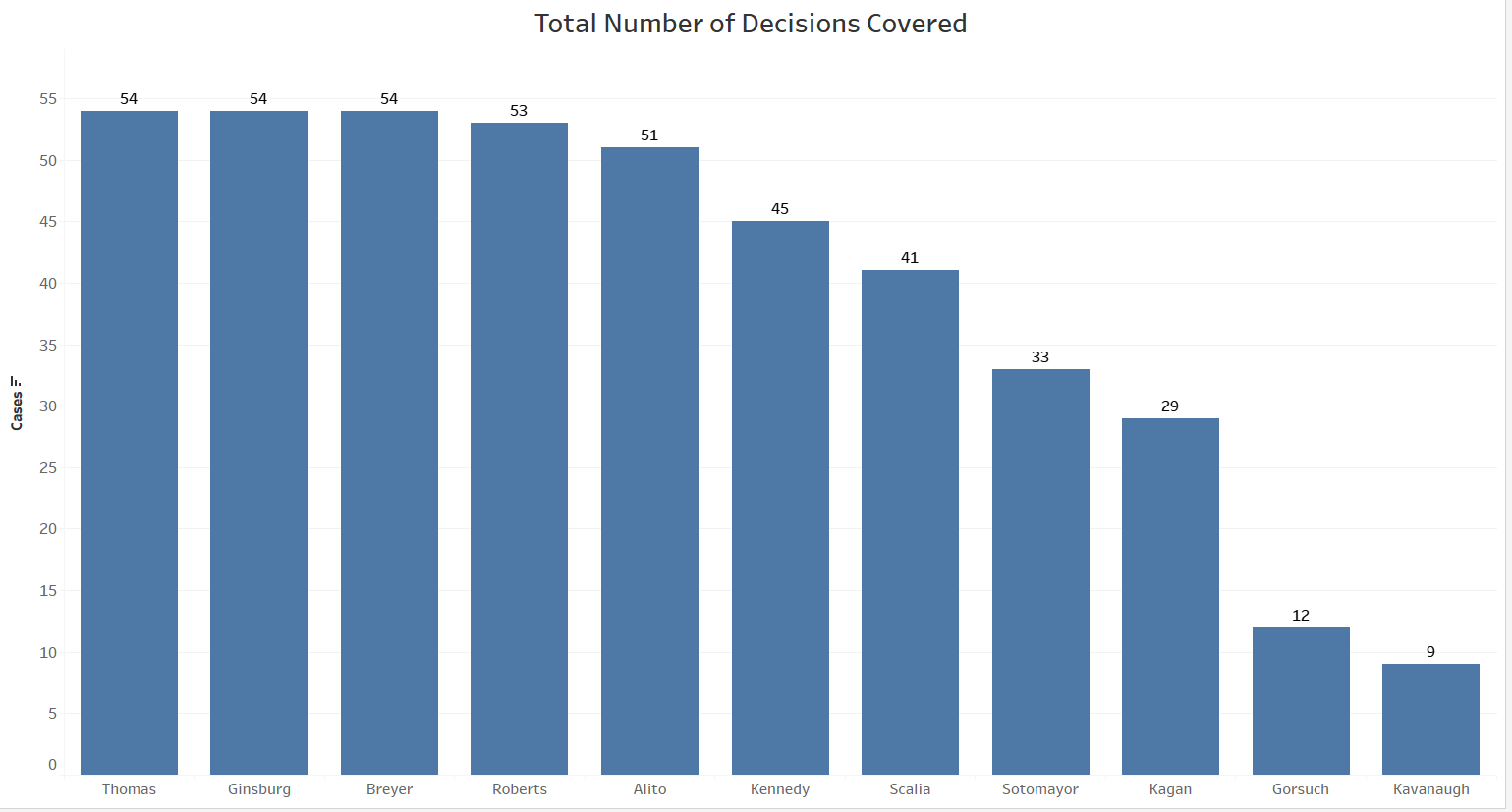

Although defining a theory of adherence to precedent is a noble cause, the possibility discussed below, that ideology combined with different visions of respect for precedent is a strong driver in such decisions, seemingly places a substantial roadblock in the way of any coherent theory. At very least, the data shows that the justices articulate a spectrum of different perspectives on the issue. Views on precedent do not necessarily reflect actions, however. The analysis below examines the justices’ deference to precedent, both when they choose to defer and when they choose not to. It looks at cases in which the court clearly reviewed past decisions since Roberts was appointed to the court in 2005. It also splits these cases into ones in which precedent was overturned (22, according to the Supreme Court Database and questions presented to the court in cert petitions) and cases in which precedent was reviewed and ultimately upheld (32, according to a case law search for the terms “stare decisis” and “overturn” near “precedent”).

Only Thomas and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer ruled in all 54 cases.

Justices Neil Gorsuch’s and Brett Kavanaugh’s rates for voting to overturn precedent should probably be viewed with a grain of salt because their case counts were low relative to those of the other justices.

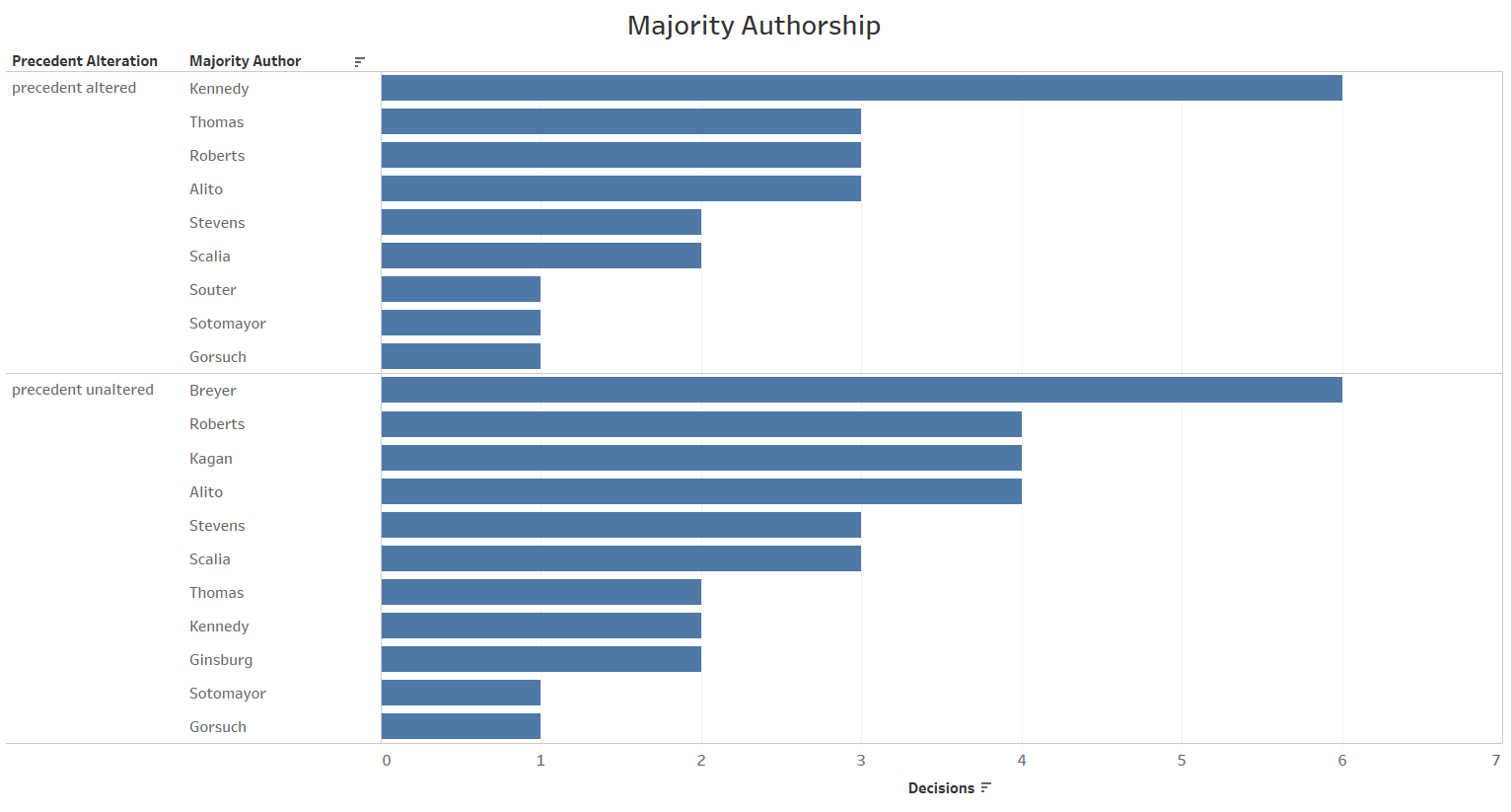

Looking at a few other summary metrics, the swing justice for the majority of the time period, Justice Anthony Kennedy, was by far the most common majority opinion author when precedent was altered.

When precedent was reviewed but went unaltered, Breyer led the way with six authored decisions, followed by Roberts, Kagan and Alito with four majority opinions each. Ginsburg, Breyer, Kagan and Kavanaugh (though he only sat in on nine of these cases) each authored no majority opinions when precedent was altered, and Justice Sonia Sotomayor authored only one. Sotomayor authored only one majority opinion when precedent was reviewed but went unaltered.

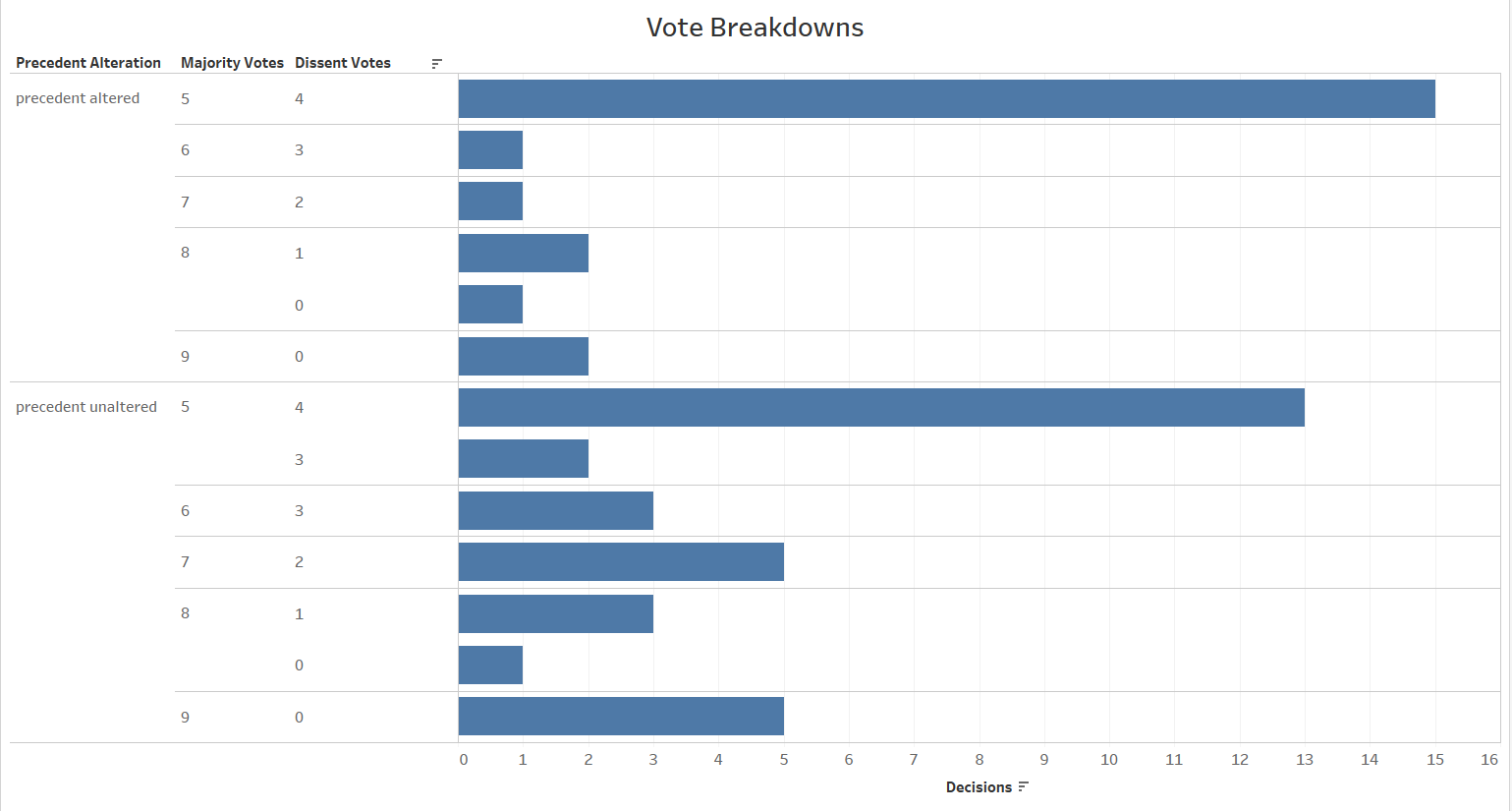

The majority of these decisions, both altering precedent and reviewing but not altering precedent, came down to 5-4 votes.

Although a small number of decisions altering precedent were unanimous, and a portion of both sets of decisions were reached by majorities of more than five justices, five-justice majorities tended to dominate both categories and were more prevalent when precedent was altered.

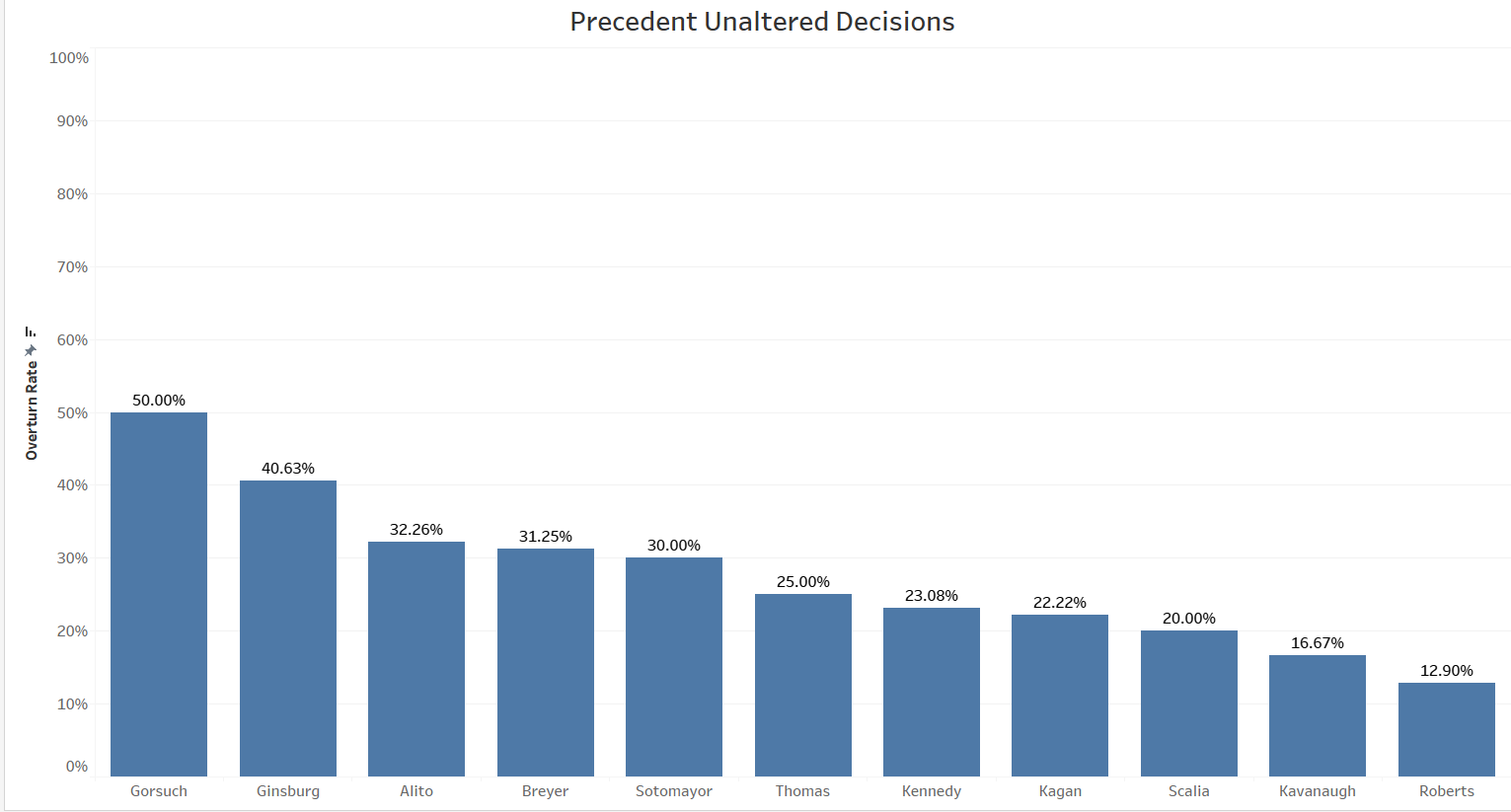

Three rates of voting to overturn precedent were calculated for each justice: in cases altering precedent, in cases that did not alter precedent and then a global rate for all cases in which they voted. First, a look at votes in favor of overturning precedent in cases in which the decision let the existing precedent stand.

Gorsuch was the only justice to reach the 50 percent overturn-vote rate threshold (though he participated in only 12 of the cases examined), with most justices’ ranges between 20 percent and the low 30s. Given that he voted in all but one decision, Roberts clearly chose to vote against overturning precedent most frequently in cases upholding precedent.

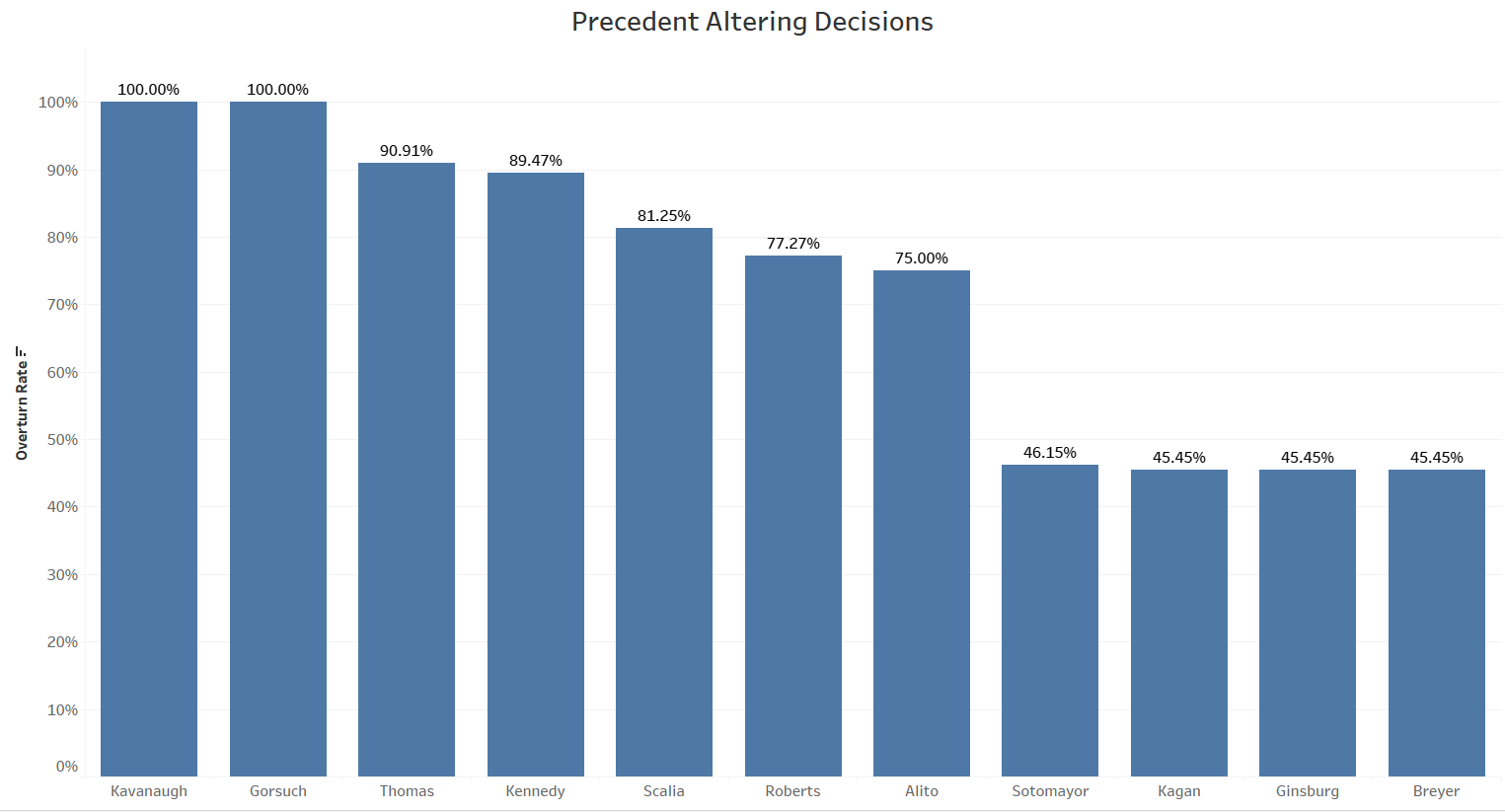

The rates begin to display more of a pattern when examining votes to overturn precedent in cases that did overturn it.

Although Roberts expounded on the need for deference to precedent in his concurrence in June Medical, he voted to overturn precedent in over 77 percent of the decisions in which the court overturned precedent since 2005 and had a greater rate than his conservative colleague Alito. The conservative justices on the court for this period all had greater rates of voting to overturn precedent than their liberal counterparts (Justices David Souter and John Paul Stevens weren’t included because they had both retired by the 2010-2011 term). Even Kennedy, the court’s swing vote, voted to overturn precedent almost 90 percent of the time when precedent was altered. These percentages mixed with the vote breakdowns underscore the point that conservative justice coalitions were by and large in the majority for these cases while liberal justices were in dissent. A question that is more difficult to untangle, and will not be undertaken in this post, is whether and to what extent ideology, as opposed to respect for precedent, was a driving factor in these decisions.

The global rates look much like the precedent-altering rates, with a few exceptions.

Gorsuch remains quite far ahead of the pack, as he voted to overturn precedent in three-quarters of the cases he helped decide in which a precedent was reviewed. The conservative justices’ rates fall mainly toward the higher end of this graph, although the differences are not as stark as they were in the precedent-altering graph.

Returning to the two justices who were both in the majority in June Medical and in dissent in Ramos, Roberts’ and Kagan’s overall rates both reflect respect for existing precedent. Although Roberts’ overall rate is the lowest of the conservative justices, it is only a few percentage points lower than Scalia’s. Kagan has the lowest rate of all the justices during this period, at just over 33 percent. This in turn supports her claim of general respect for the court’s past rulings.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.