Empirical SCOTUS: Justices’ separate opinions suggest high polarization outside the regular merits docket

Over the past five Supreme Court terms, the justices have issued 157 separate “opinions relating to orders.” These orders, which are issued without oral arguments and without full merits consideration, typically fall into three categories: denials of cert petitions, rulings on emergency requests for relief in pending cases, and summary reversals of lower court decisions. We do not necessarily know all of the justices’ votes on these orders – only the ones the justices choose to make public through a brief note of their dissent or by signing onto a separate opinion. But an analysis of the publicly disclosed votes in such cases shows a high degree of polarization among the justices. Of the 157 separate opinions relating to orders that have been issued in the past five years, only two were joined by at least one conservative and one liberal justice. Both were joint dissents from Justices Neil Gorsuch and Sonia Sotomayor in orders relating to criminal cases. The other 155 separate opinions were either solo-authored or were joined by justices from the same ideological camp.

In some ways, the justices’ positions in these non-merits rulings are the best ways to gauge their ideologies relative to one another. That’s because the decision to write separately, or to join another justice’s separate opinion, is truly discretionary. Justices do not need to write anything on these orders – or even publicly record their votes – so they author or sign onto separate opinions only when they feel especially compelled to do so. Because these cases are not on the court’s merits docket, none of the strategic posturing concerns are in play. With this in mind, we can get a much clearer position of the justices’ actual positions on discrete issues. Steve Vladeck recently showed how this is the case with his analysis of “shadow docket” decisions where the solicitor general plays a role.

How were the justices aligned in their separate opinions relating to orders over the past five terms? The following chart shows the opinion counts from each permutation of justices, including solo authorships.

As mentioned above, the only cross-ideological grouping came from the two opinions – both authored by Gorsuch and joined by Sotomayor – dissenting from cert denials in Hester v. United States and Stuart v. Alabama.

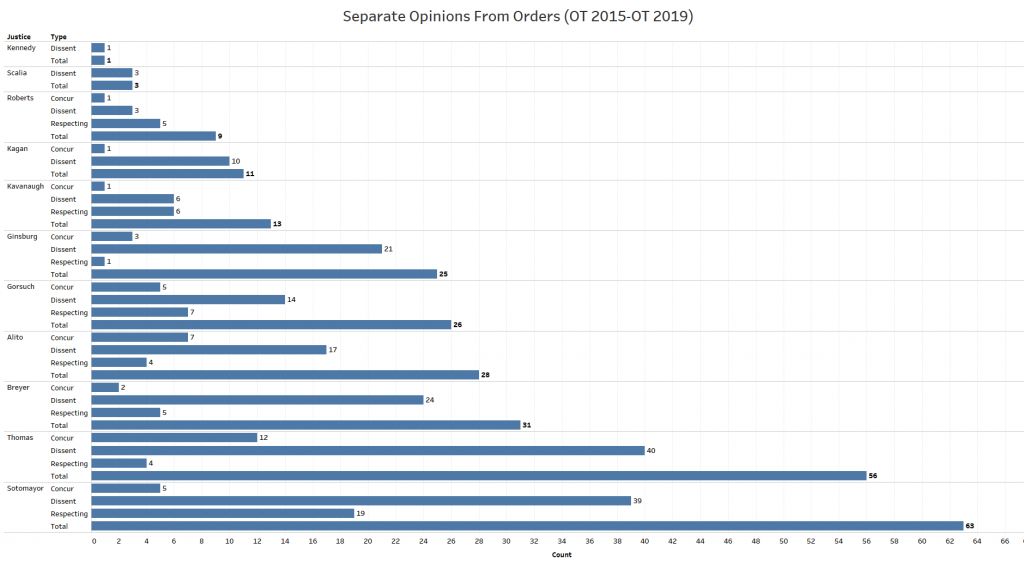

Sotomayor was the most active justice in these separate opinions. The following chart breaks down the justices’ separate opinion totals (the opinions they joined as well as authored) by opinion type.

Justice Clarence Thomas was right behind Sotomayor in terms of overall opinion participation. That’s not surprising: Thomas authored the highest number of separate merits opinions this past term and tends to be the most prolific dissenter on the Roberts court. Among the justices who sat on the court for all of the past five terms, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Elena Kagan were the least involved in separate opinions relating to orders and were less involved even than Gorsuch and Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who both joined the court in the middle of this five-term period.

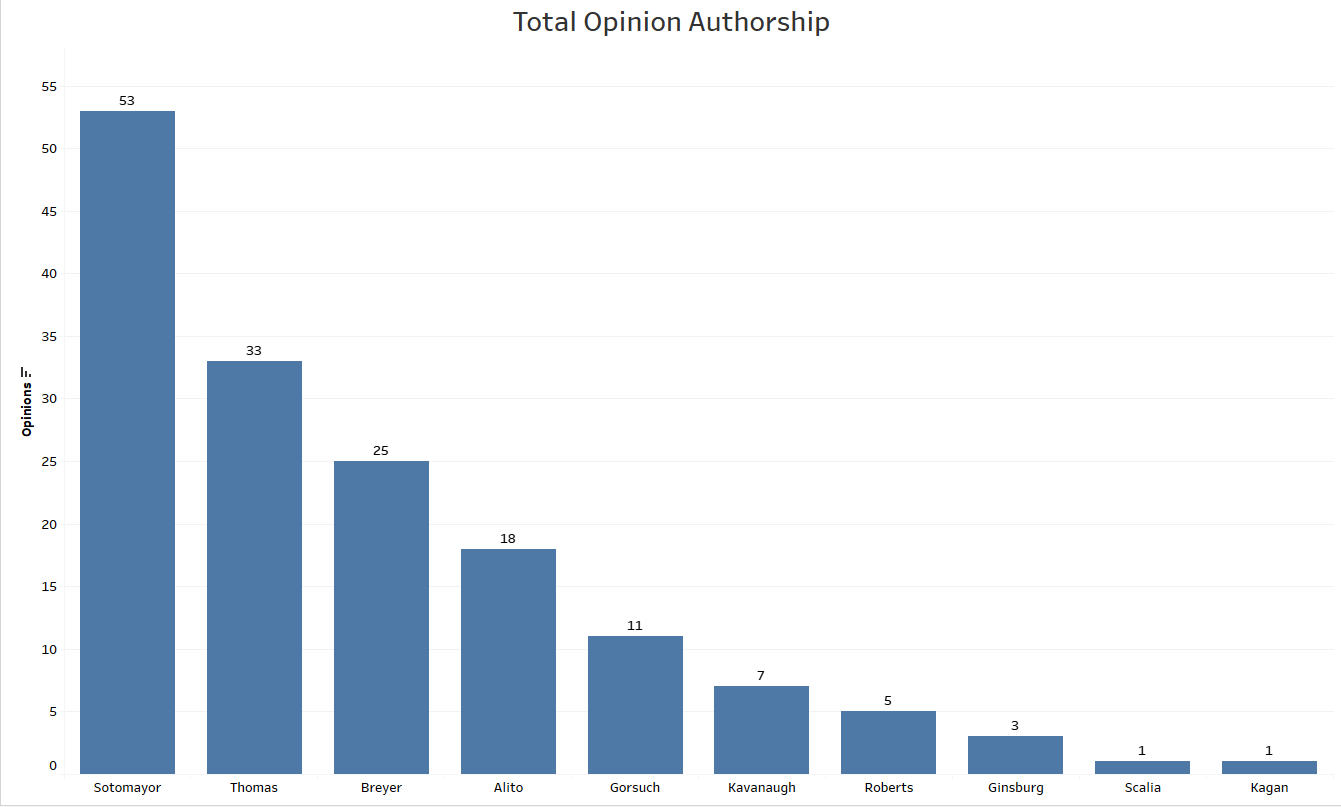

Sotomayor appears to dominate most metrics for separate opinions relating to orders, though. Along with signing onto the most separate opinions during the five-term period, she also authored more of these separate opinions than any other justice.

We can also look at the justices’ separate authorship on a term-by-term basis, as the graph below depicts.

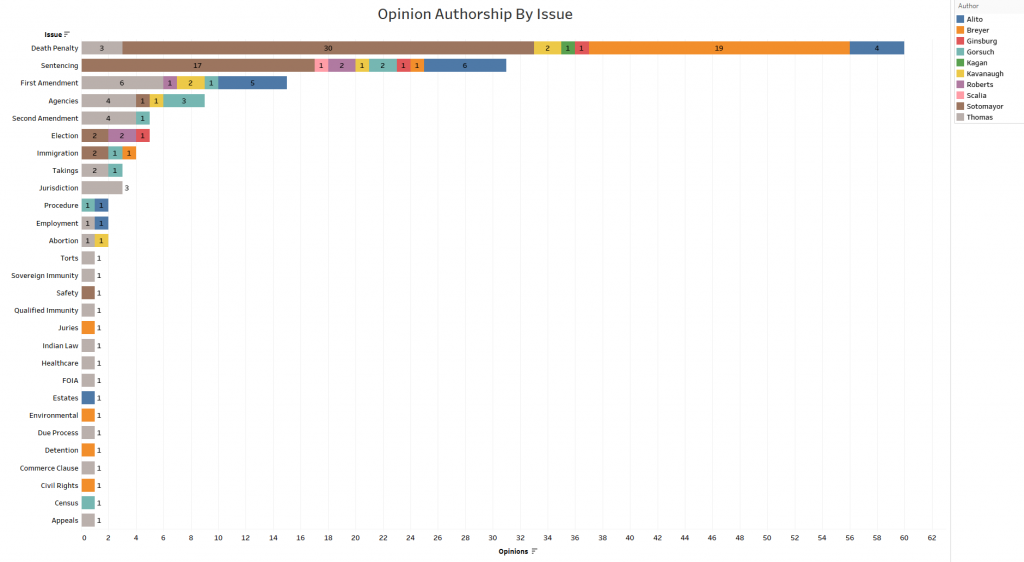

Much of Sotomayor’s activity in this area stems from her regular dissents from emergency orders the court issues in death penalty cases. Indeed, separate opinions in death penalty cases are the most frequent opinions relating to orders overall, as the graph below shows. But capital punishment is by no means the only issue that garners a significant number of opinions relating to orders.

Along with issues of criminal justice, on which Sotomayor has become the most vocal justice, Thomas is deeply engaged and vocal in cases dealing with First and Second Amendment rights as well as in cases dealing with Chevron deference to agency decision-making. Several areas that have drawn a mixed bag of authorship of opinions relating to orders include election law, immigration, eminent domain and Article III jurisdiction.

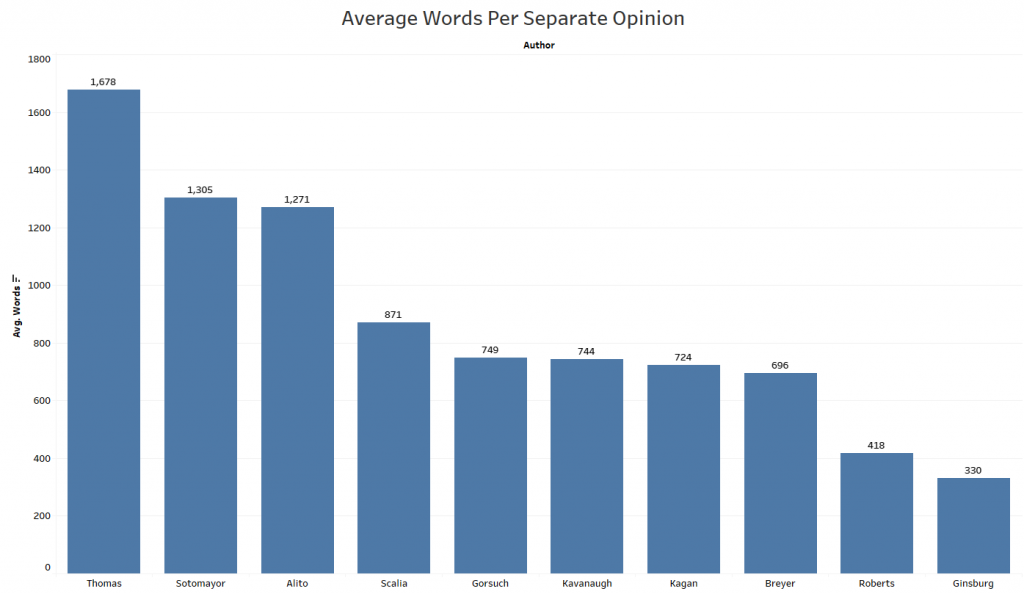

One other metric relating to the justices’ participation in these separate opinions deals with the length of the opinions. The following graph shows the average word length for the justices’ separate opinions relating to orders.

Thomas, on average, authored the lengthiest separate opinions by far, followed by Sotomayor and Alito, while Roberts and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg authored the shortest such opinions on average. Thomas authored the single longest opinion relating to an order during this period, a dissent from the denial of Second Amendment petition Rogers v. Grewal (6,200 words). The two next-longest opinions came from Sotomayor relating to two death penalty petitions: Arthur v. Dunn (5,572 words) and Elmore v. Holbrook (4,534 words). Rounding out the top five, Alito authored lengthy opinions relating to the First Amendment petition Stormans v. Wiesman (4,449 words) and the death penalty petition Murphy v. Collier (4,376 words). All five of these lengthy opinions were dissents.

There is much to be learned from the justices’ separate opinion practices in these cases. The justices’ ideological levelling – with Roberts leading the way as an unpredictable vote in high-profile merits decisions – that has been described so often at the end of the 2019-20 term may not tell all of the story. These separate opinions, some of the only truly discretionary decisions that we get to see from the justices, show that the justices may be more polarized than ever before. Sotomayor and Thomas are the leading voices in these opinions, though regarding vastly different issues. If the justices have any sway with their separate opinions relating to orders, they will convince their colleagues to take up these issues in future cert petitions and change the direction of the law according to their own vision.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS