Empirical SCOTUS: Interesting meetings of the minds of Supreme Court justices

on Jun 15, 2020 at 2:15 pm

Unanimity in the Supreme Court used to be the norm. In the early years of court history there were few dissents, and so there was little opportunity to examine differences between the justices outside of how they authored their majority opinions. This practice has changed over the years, and now decisions are more frequently divided rather than unanimous.

Certain justices are also more likely to vote alongside, or against, one another. Differences in voting agreements can be somewhat staggering. Last term, for instance, Justice Clarence Thomas agreed with Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Neil Gorsuch, Samuel Alito and Brett Kavanaugh at least 75 percent of the time. By contrast, he agreed with Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor only 50 percent of the time, with Justice Stephen Breyer 51 percent of the time and with Justice Elena Kagan 60 percent of the time. Sotomayor agreed with Kagan, Breyer and Ginsburg at least 85 percent of the time. Besides agreeing with Thomas only 50 percent of the time, as noted above, Sotomayor voted with Roberts 67 percent of the time, with Alito 57 percent of the time, with Gorsuch 63 percent of the time and with Kavanaugh 64 percent of the time.

These agreement levels are based on unanimous as well as divided votes and refer to agreement at least in part, meaning the two justices together joined at least one majority, concurring or dissenting opinion. The majority of the time justices like Thomas and Sotomayor vote together, other justices vote alongside them as well. Seldom do we see justices who often disagree vote together in isolation. Thomas and Sotomayor only once voted together without any other justices, in dissent from the 2016 decision in Voisine v. United States.

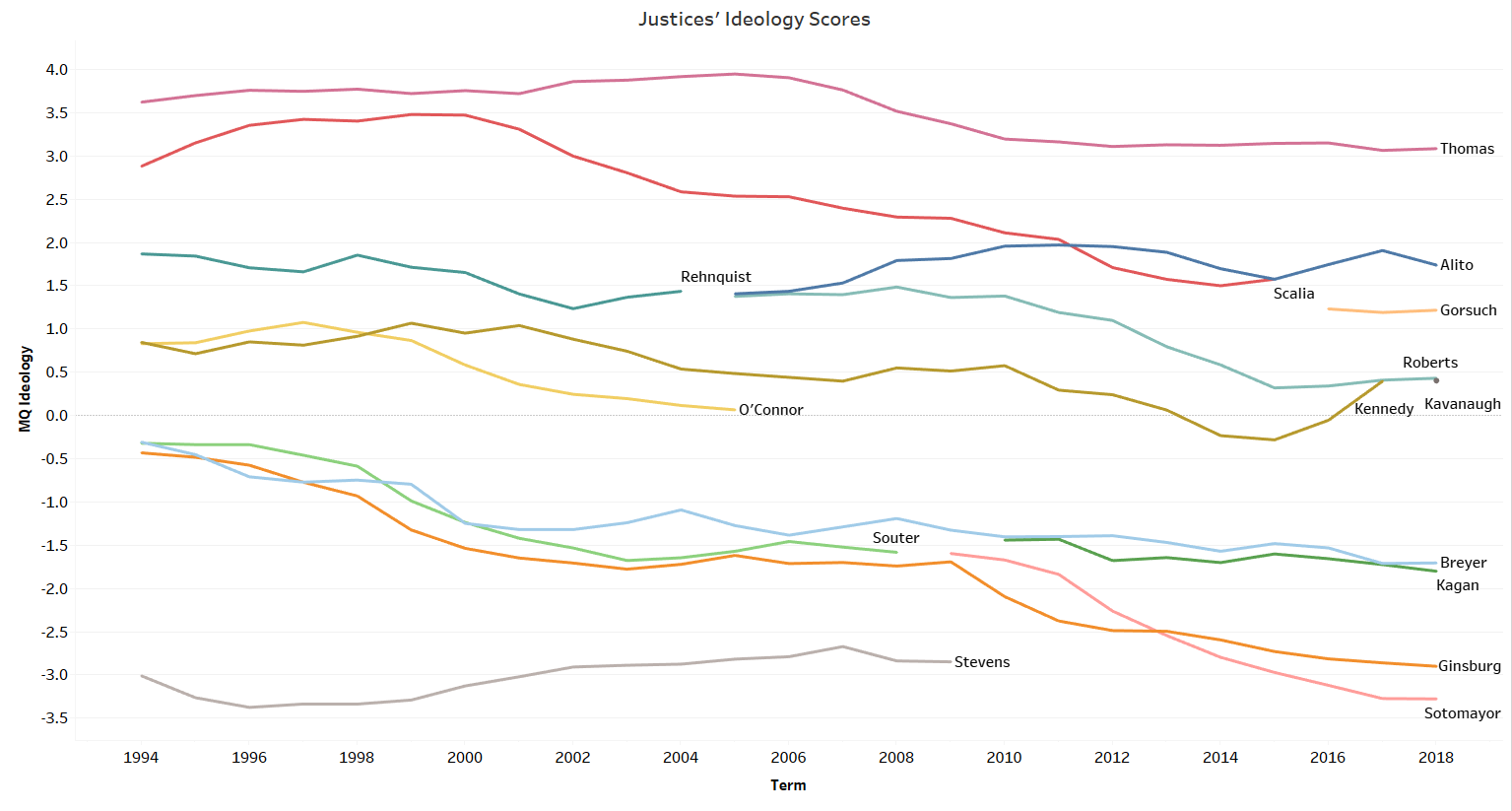

Over time the justices’ agreements are captured in certain ideology measures. Martin Quinn (MQ) Scores, for instance, are based on justices’ voting agreements, as justices with closer scores vote together more frequently, and the distance between justices’ scores increases as they vote together less frequently. Positive MQ Scores equate to a more conservative ideology and negative scores equate to a more liberal ideology. Ideology in this context, however, is merely a function of voting alignment. The justices’ MQ Scores for the 1994 through 2018 terms are shown in the graph below.

This period is important because it begins with Breyer’s first year on the court. After Breyer joined the bench, the court’s membership was stable until Chief Justice William Rehnquist passed away in 2005. The justices tend to cluster into three groups. The more liberal justices have more negative numbers and include Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor and Kagan as well as Justices David Souter and John Paul Stevens. The more conservative justices have more positive numbers and include Roberts, Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh as well as Rehnquist and Justice Antonin Scalia. Justices Anthony Kennedy and Sandra Day O’Connor, although both relatively conservative, were the most moderate justices during this period and fall toward the middle of the graph.

We do not often expect to see a conservative justice vote along with one or more liberal justices, nor a more liberal justice vote along with one or more conservative justices. We have only seen this twice so far in argued cases decided this term: In Thryv v. Click-To-Call Technologies Sotomayor and Gorsuch dissented together, and in Ramos v. Louisiana Kagan dissented alongside Alito and Roberts. This is the first time that we have seen either of these dissenting coalitions, and coincidentally, both of these decisions were released on the same day (April 20, 2020).

Because these cross-ideological coalitions do not arise very frequently, it is interesting to consider when and why they occur. Commentators suggested that Kagan’s reasons for dissenting in Ramos, in which the court overruled an earlier case to hold that the Constitution requires a unanimous jury verdict in state criminal trials, were different than Roberts’ and Alito’s. According to this argument, Roberts’ and Alito’s votes in Ramos stemmed from a more conservative approach, while Kagan was motivated by a concern for precedent. She expressed a similar concern last term in her powerful dissent in Knick v. Township of Scott, in which she questioned the basis for the majority’s overturning the decision in Williamson County Regional Planning Comm’n v. Hamilton Bank of Johnson City.

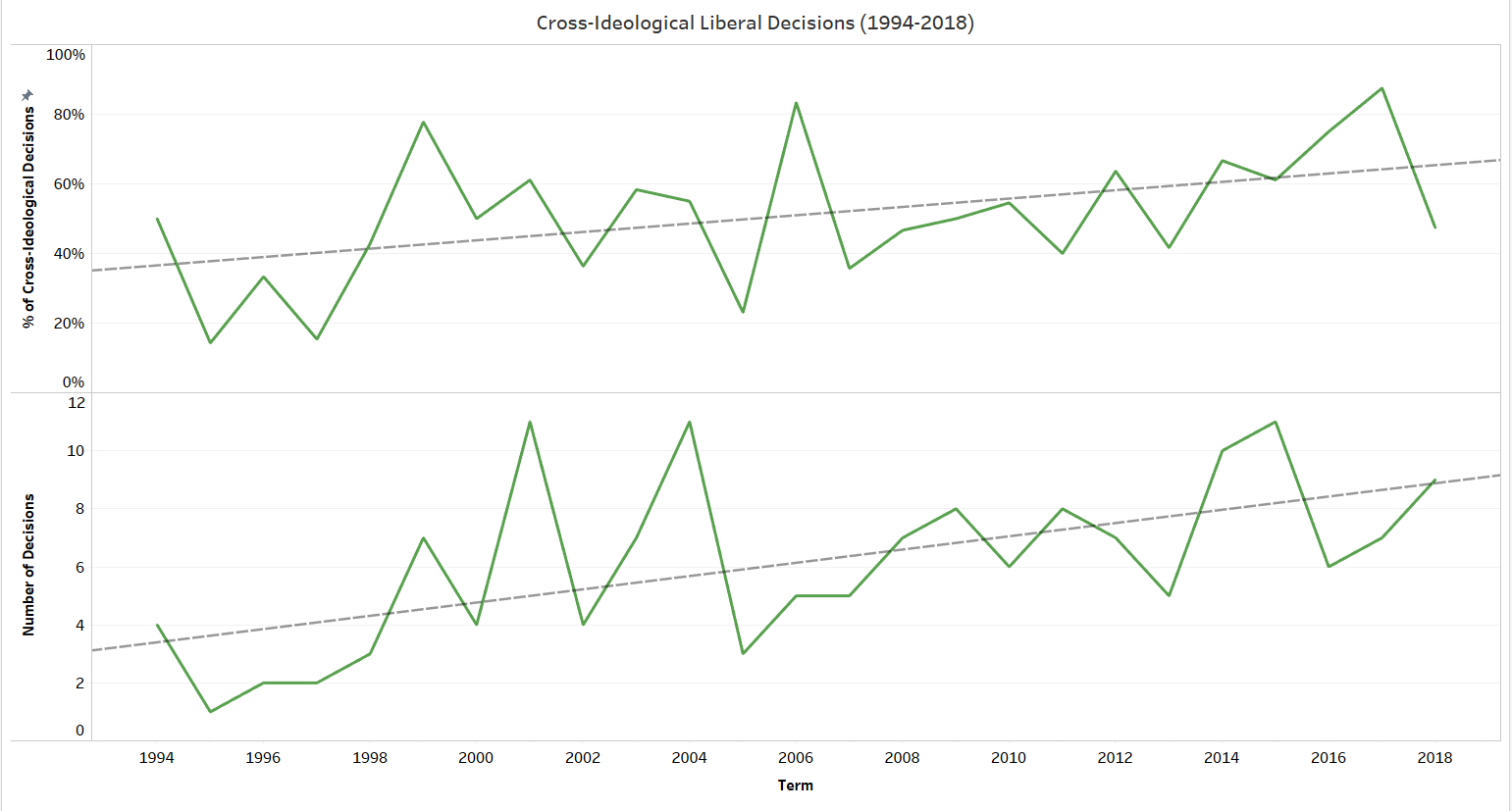

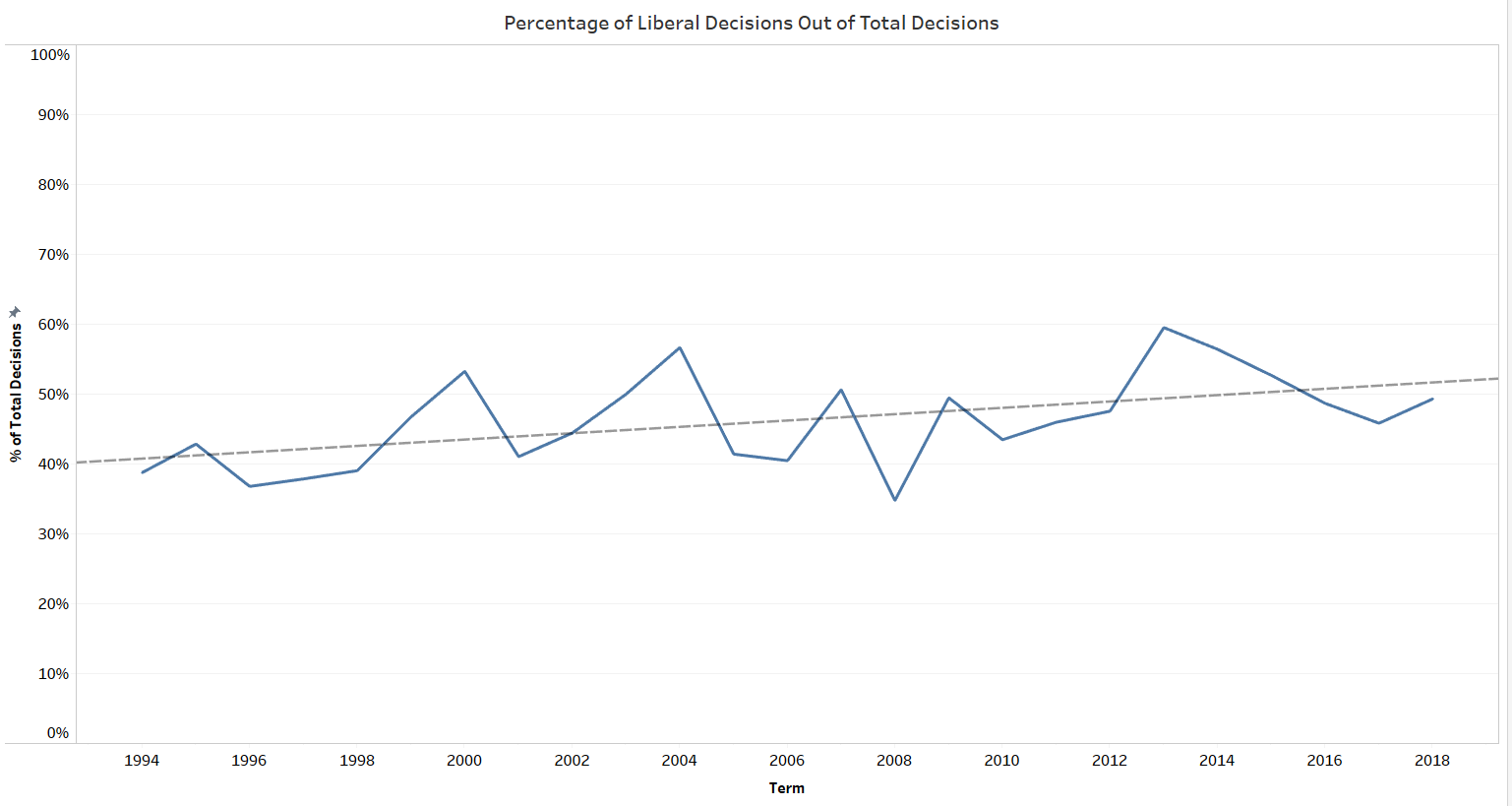

Pooling all the cases with such cross-ideological votes since the 1994 term, we see a few trends of interest. First is an uptick in these votes in decisions with liberal outcomes, according to data from the United States Supreme Court Database, which codes most of the court’s decisions as conservative or liberal. The following graphs show both the fraction and the overall number of liberal decisions with cross-ideological votes on top and the percentage of liberal decisions in all cases below. The gray lines show the trends over time.

Liberal decisions have been trending upward, moving from 40 percent of all decisions in 1994 to over 50 percent of decisions in 2018. This includes unanimous as well as divided decisions. Liberal decisions have increased at about double that pace among cases with cross-ideological votes, from under 40 percent of those cases in 1994 to over 60 percent in 2018.

Justices may be strategically moderating their positions on specific issues to reach cross-ideological consensus, and the fact that liberal justices are outnumbered by their more conservative counterparts suggests that liberal justices might be more strategic about moderating their positions to bring in a conservative justice to create a majority or to join ideologically distant colleagues in dissent.

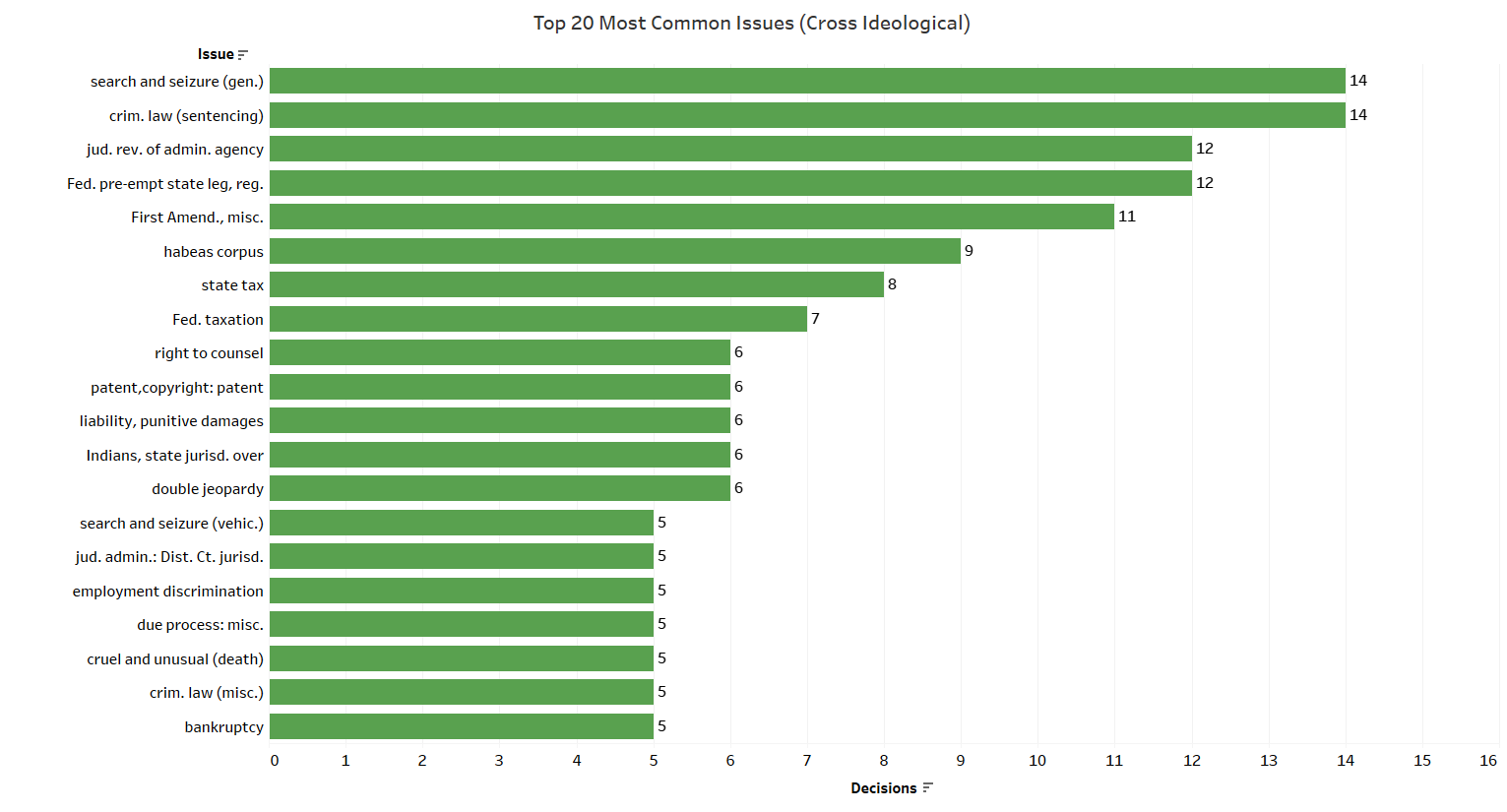

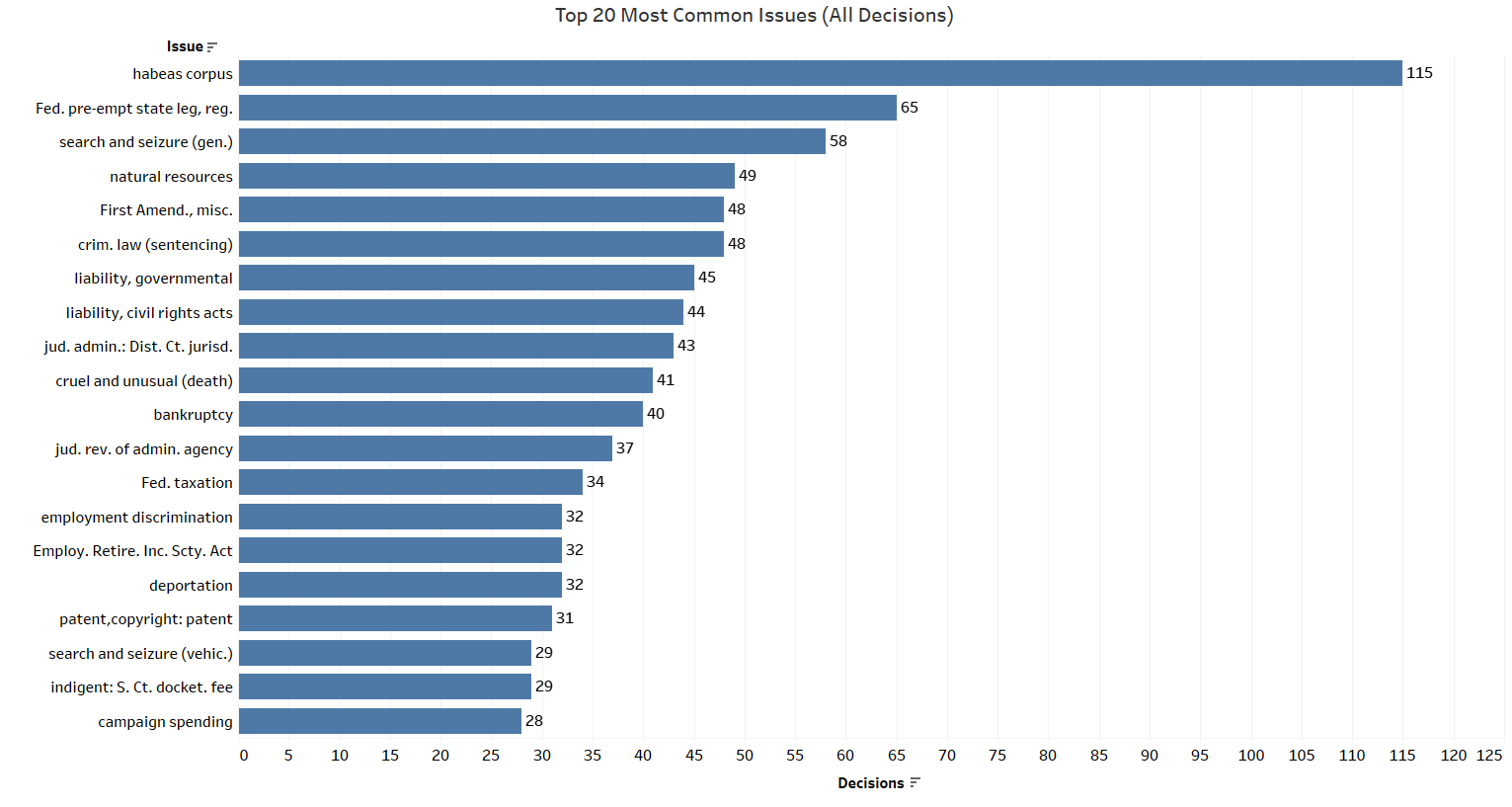

When we break down both cases with cross-ideological votes and all cases from OT 1994 to 2018 by issue, we see differences between the two groups. The cross-ideological graph is on the top and the all-decisions graph is on the bottom.

Habeas cases dominate the court’s main docket, dwarfing other issues in comparison. They are less common among cases with cross-ideological votes. Search-and-seizure and criminal sentencing cases most often produce cross-ideological votes. Both are important issues in the court’s main docket, although several issues are more dominant than criminal sentencing, including natural resources and the First Amendment.

Another important area for cross-ideological votes is judicial review of administrative agency actions. This issue is also within the top 20 issues on the court’s main docket, although it falls much lower on the list.

State- and federal-tax cases are both high on the cross-ideological case list. Although federal taxation makes it onto the court’s main docket list, state taxation does not. Other issue areas on the cross-ideological list that are not on the court’s main issue list include:

- Right to counsel

- Punitive damages

- State jurisdiction over Indian law cases

- Double jeopardy

- Due process

- Miscellaneous criminal law

Case areas on the court’s most common issue list that are not on the cross-ideological list include:

- Natural resources

- Government and civil rights liability

- ERISA

- Deportation

- Campaign finance

- Supreme Court docket fees for indigent petitioners

One further difference we see between the court’s overall merits docket and cases with cross-ideological votes is with majority decision authors. Opinion authorship for the court’s merits docket is generally spread evenly among the justices. This is not so for decisions with cross-ideological votes, which by definition raise issues that divide the justices in interesting ways. Based on the theory of bargaining and opinion assignment, this in turn leads to assignment of the majority opinion to a justice who is able to speak for the fractured majority in each particular decision.

This post was originally published on Empirical SCOTUS.