Empirical SCOTUS: How Chief Justice Roberts articulates his ethos through his Year End Reports

on Jan 8, 2020 at 10:23 am

Chief Justice John Roberts released an impassioned Year End Report on December 31, 2019, which generated much commentary. The New York Times, for instance, wrote about Roberts’ calls for an independent federal judiciary. The Wall Street Journal examined his warnings against rumor and false information. These values inherent in the report foreshadow important aspects related to the (presumably) upcoming Senate impeachment hearings, over which Roberts will preside. Although these allusions clearly relate to current politics, Roberts did not stray drastically from the substance in his previous Year End Reports, nor from topics he discusses in some of his most well-known decisions. This post looks at some of the key words Roberts uses in Year End Reports.* It also looks at some of the top words in his opinions issued in the month of June, when the court tends to release its most important opinions. Roberts often steeps his prose in the court’s history and is not averse to discussing the relationship between politics and the court. We can see these facets of his writing in his word choice in both sets of texts.

One of the more profound statements in Roberts’ 2019 Year End Report came in the second-to-last paragraph:

We should celebrate our strong and independent judiciary, a key source of national unity and stability. But we should also remember that justice is not inevitable. We should reflect on our duty to judge without fear or favor, deciding each matter with humility, integrity, and dispatch. As the New Year begins, and we turn to the tasks before us, we should each resolve to do our best to maintain the public’s trust that we are faithfully discharging our solemn obligation to equal justice under law.

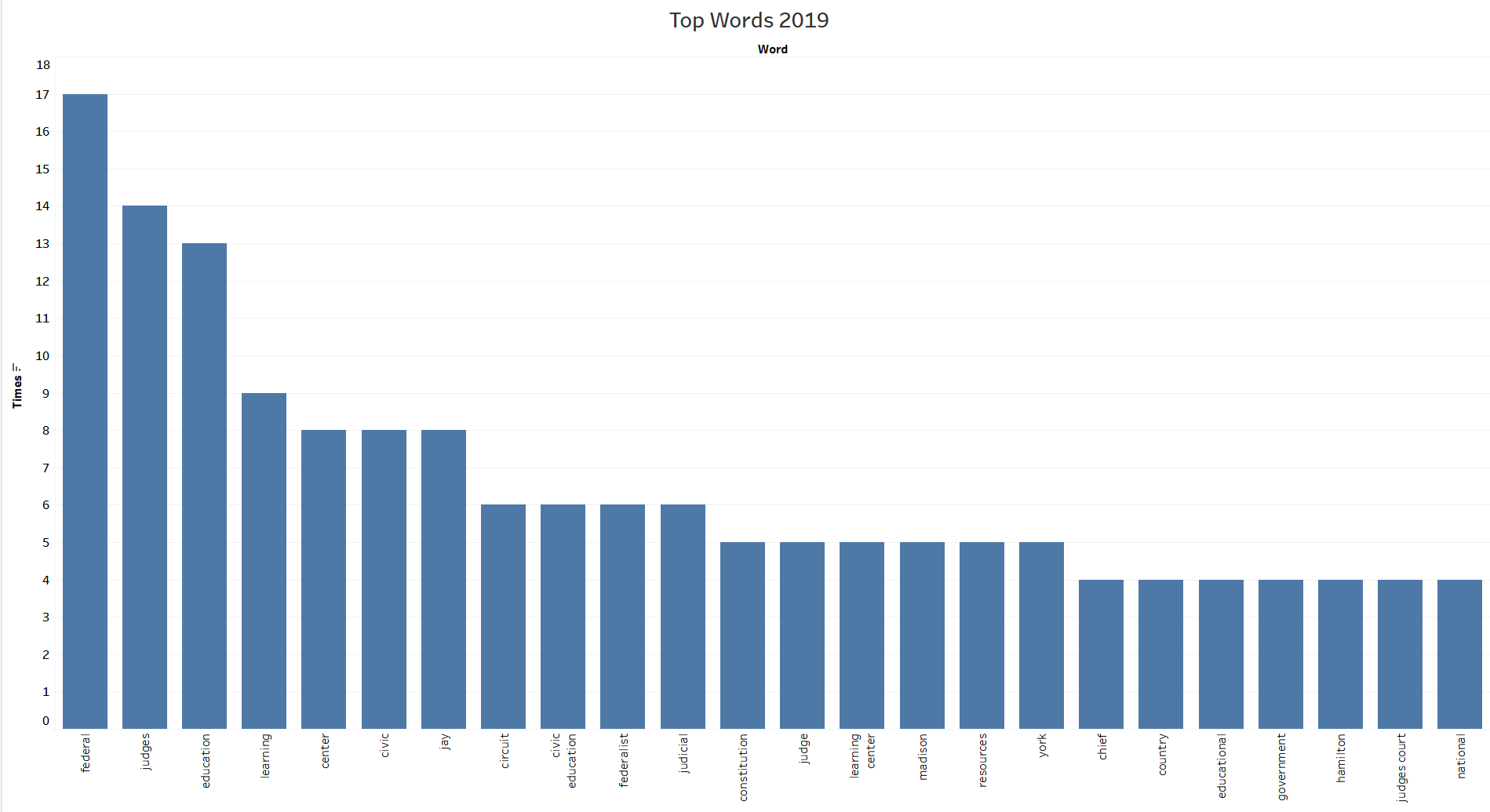

This notion of trust in the judiciary is central to Roberts’ philosophy of the court. It is so crucial that Roberts gave one of his very few public comments defending the federal judiciary after President Donald Trump criticized the decision of an “Obama Judge” who ruled against the president’s migrant asylum policy. The trust and judicial independence that Roberts focused on in the 2019 Year End Report echoed themes espoused in the Federalist Papers. This is clear from many of the report’s top terms.

Although some of the top terms are common words that appear across many of Roberts’ Year End Reports, mainly dealing with judges and their role in civic education, we see that “federalist” (relating to the Federalist Papers) came up six times, while the authors of the papers were mentioned often as well: John Jay eight times, James Madison five times and Alexander Hamilton four times. We see these words’ purpose in passages that underscore the importance of living under a democratic government:

Happily, Hamilton, Madison, and Jay ultimately succeeded in convincing the public of the virtues of the principles embodied in the Constitution. Those principles leave no place for mob violence. But in the ensuing years, we have come to take democracy for granted, and civic education has fallen by the wayside.

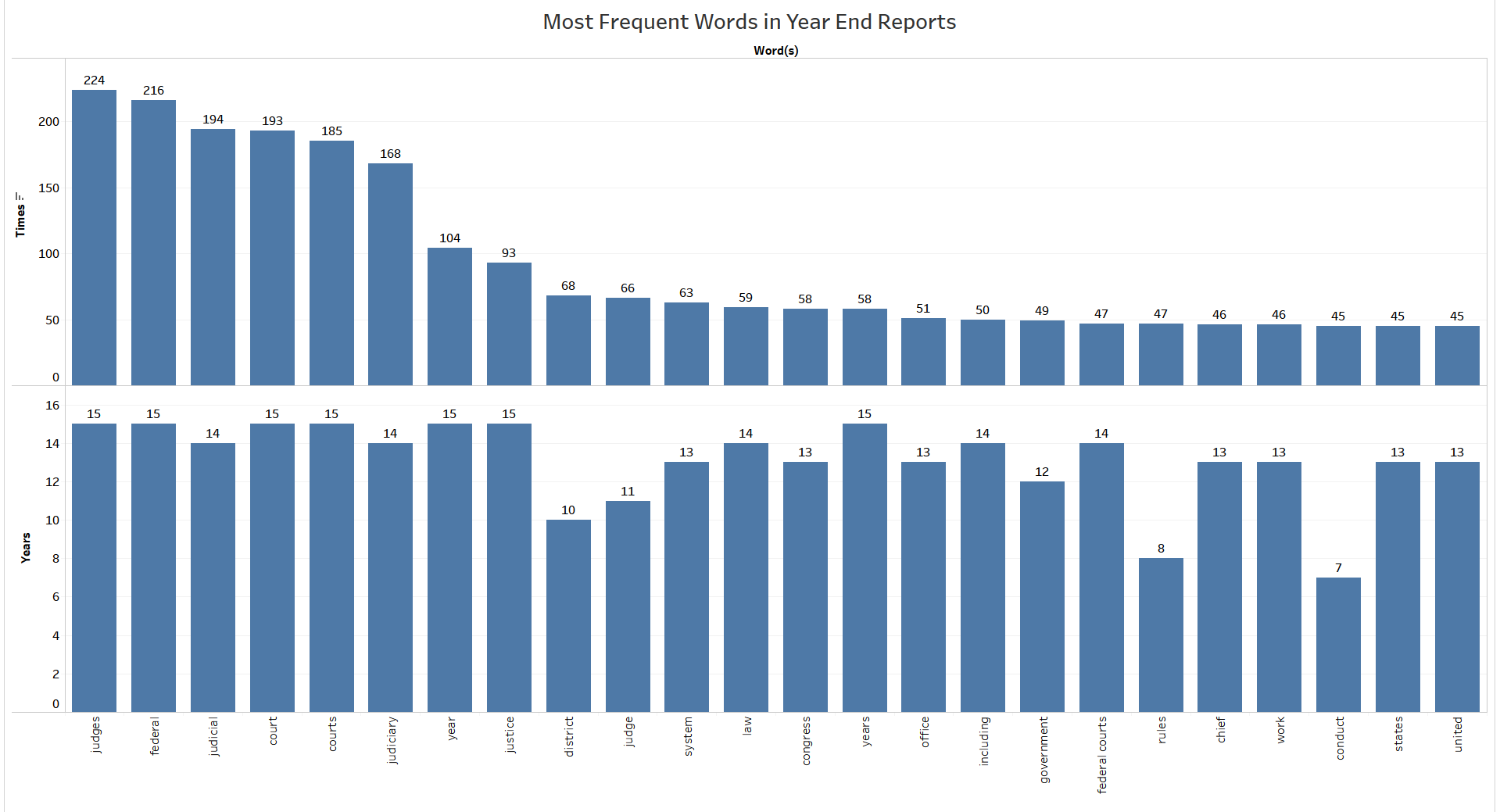

Looking across all Roberts’ Year End Reports since he took over the role of chief justice in 2005, we see that he tends to focus on concepts essential to courts and the rule of law. The top row shows the number of times words have arisen, and the bottom row shows the number of reports in which the words appeared (the maximum is 15).

Many of these words are specific to courts and judges, but others signify broader topics. Some examples include “system,” which was used 63 times in 13 reports, “Congress,” which was mentioned 58 times in 13 reports, and “government,” which was discussed 49 times in 12 reports. An example of the uses of system comes from Roberts’ 2005 report: “I also understand that it is the responsibility of Congress to do difficult things when necessary to preserve our constitutional system. Our system of justice suffers as the real salary of judges continues to decline.” In ways like this, Roberts expands his discussion beyond the courts to the federal government more generally.

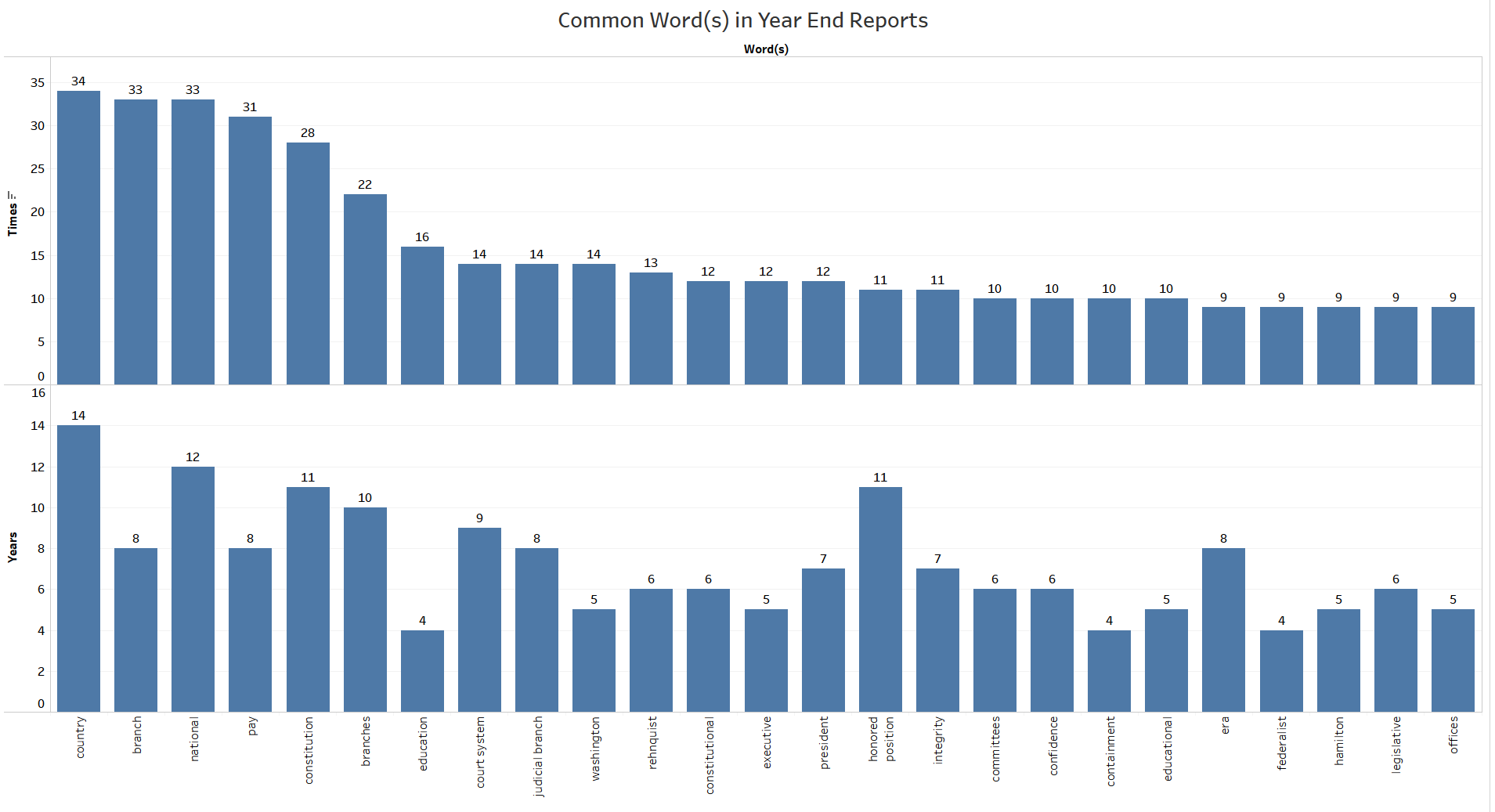

A look at some other common, though less frequent, words in Roberts’ Year End Reports reveals additional trends.

“Branches” of government are described 22 times in 10 reports, “constitution” appears 28 times in 11 reports, “executive” comes up 12 times in five reports, and the “president” is used 12 times in seven reports. In addition, various individuals are the subject of frequent discussion, including former Chief Justice William Rehnquist, mentioned 13 times in six reports, and Hamilton, who came up nine times in five reports.

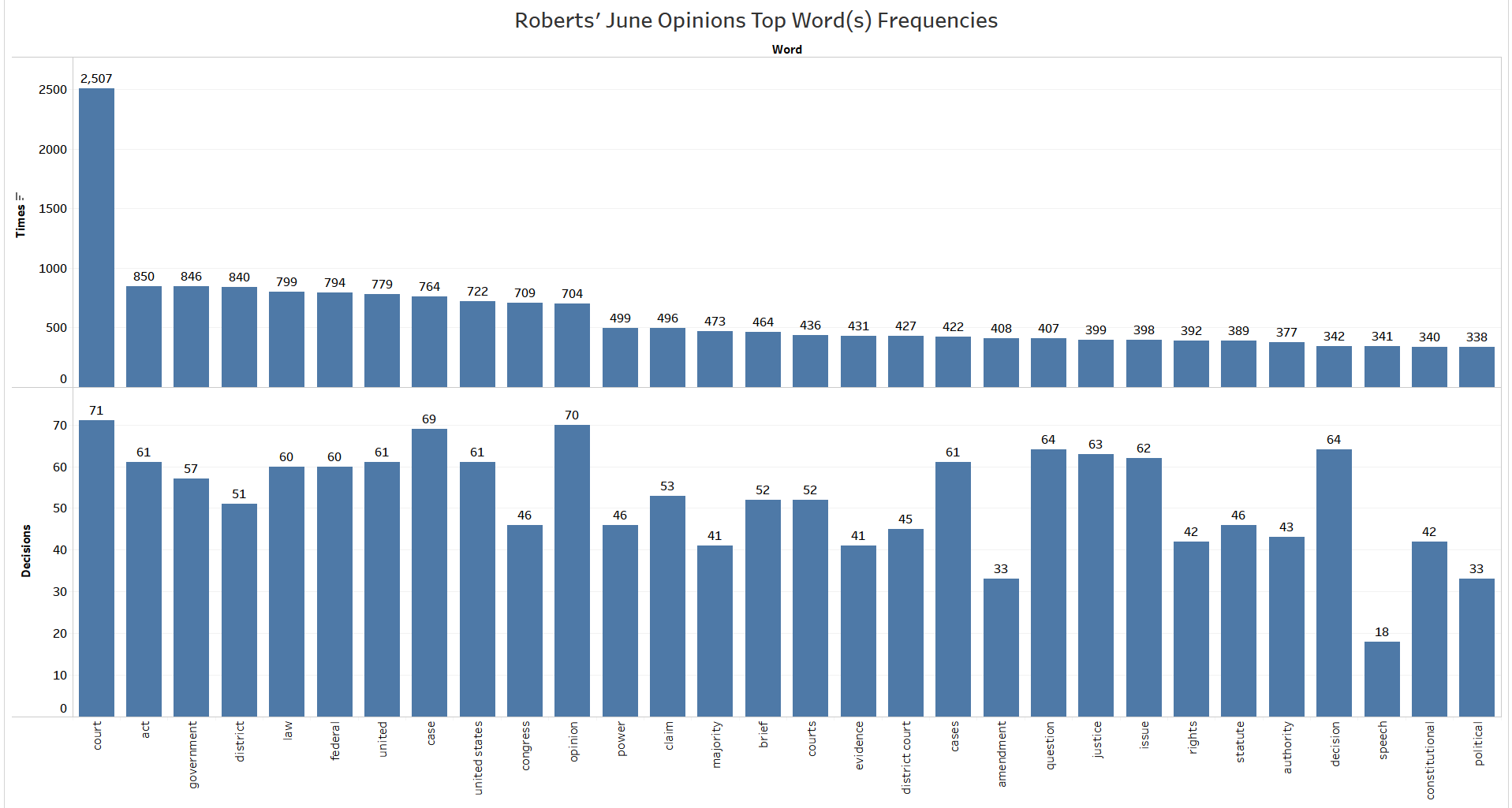

When we look at the top words that appear in the 71 opinions Roberts has authored that were released in June (consisting of 38 majority opinions, 25 dissents and eight concurrences), the topics are fairly consistent with the main words in his Year End Reports.

“Court,” “government,” “law,” “federal,” “United States” and “Congress” are all top-frequency words from Roberts’ Year End Reports. Some additional political notions also arise frequently in these opinions. “Power” was mentioned 499 times across 46 opinions, “rights” came up 392 times in 42 opinions and “political” came up 338 times in 33 opinions.

“Power” came up most frequently (134 times) in Roberts’ majority opinion in NFIB v. Sebelius, examining the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act. “Rights” are discussed the most (43 times) in Roberts’ majority opinion in Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior Univ. v. Roche Molecular Systems. Finally, the term “political” came up the most in Roberts’ majority opinion in last term’s Rucho v. Common Cause, which held that partisan gerrymandering presents a political question beyond the reach of federal courts.

None of these June opinions, however, is the most similar in terms of word composition to Roberts’ 2019 Year End Report. Using a method called cosine similarity, described as “a metric used to measure how similar the documents are irrespective of their size,” the three most similar opinions to the 2019 Year End Report are Roberts’ 2011 majority opinion in Stern v. Marshall and his 2008 dissents in Boumediene v. Bush and Sprint Communications v. APCC Services.

Where are the similarities between these opinions and Roberts’ 2019 Year End Report? Stern demonstrates how an unlikely opinion mirrors concepts from the report. Much of the case discussion surrounds the extent to which Article III authorizes Bankruptcy Court judgments. In one section Roberts performs a historical analysis:

Article III protects liberty not only through its role in implementing the separation of powers, but also by specifying the defining characteristics of Article III judges. The colonists had been subjected to judicial abuses at the hand of the Crown, and the Framers knew the main reasons why: because the King of Great Britain “made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.” The Declaration of Independence ¶ 11.

As this passage makes apparent, it is not always the predictable cases in which Roberts’ opinions raise the same concepts and concerns as do his Year End Reports. Nonetheless, the themes in Roberts’ opinions and Year End Reports often have implications that extend beyond specific cases to political ideals and expectations for a well-functioning democracy.

*When processing the text, one- and two-word phrases were included. A stoplist dictionary removed generic words such as “and” and “the.” Words under two characters were removed.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.