Empirical SCOTUS: The beginning of the 2019 term and how it stacks up

on Dec 24, 2019 at 11:36 am

June is traditionally the month when the public focuses on the Supreme Court. Many of the court’s most politically tinged decisions in recent years were rendered during June. These include Rucho v. Common Cause and Department of Commerce v. New York (the census case) last term, Janus v. State, County, and Municipal Employees and Trump v. Hawaii the previous term, and Trump v. International Refugee Assistance Project the term before that. Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt was decided in June, as were Obergefell v. Hodges and King v. Burwell. By contrast, relatively overlooked decisions are rendered in the early months of each term. These often include a plethora of unsigned decisions. This post looks at differences in decisions early in terms (between October and December) and later in terms (between January and June).

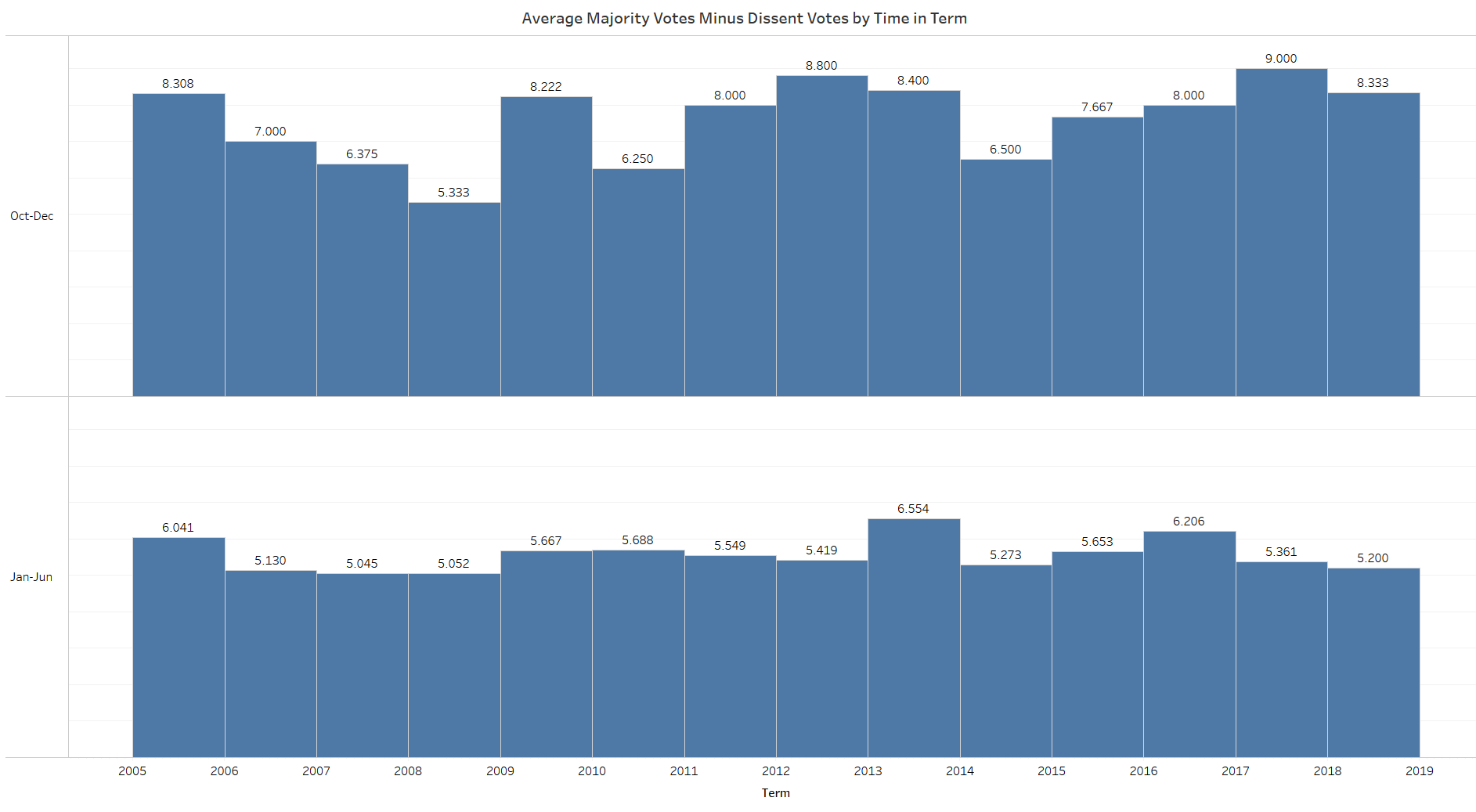

One way to gauge case importance and the justices’ different perspectives in cases is through the difference in votes between the majority and dissent in a case. Although not universally the case, decisions that are less divided often do not generate the same kind of publicity as cases that precipitate rifts among the justices. Between the 2005 and 2018 terms, the average vote split across cases is noticeably different early and late in terms.

Although many of the terms show average vote differences between October and December at eight votes or more (with one or zero dissents), signaling primarily unanimous decisions, the differences are much smaller for the latter part of terms, pointing to much greater dissensus among the justices. Of the three decisions rendered so far during the 2019 term, two were 9-0 decisions and one, Rotkiske v. Klemm, was 8-1 with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissenting.

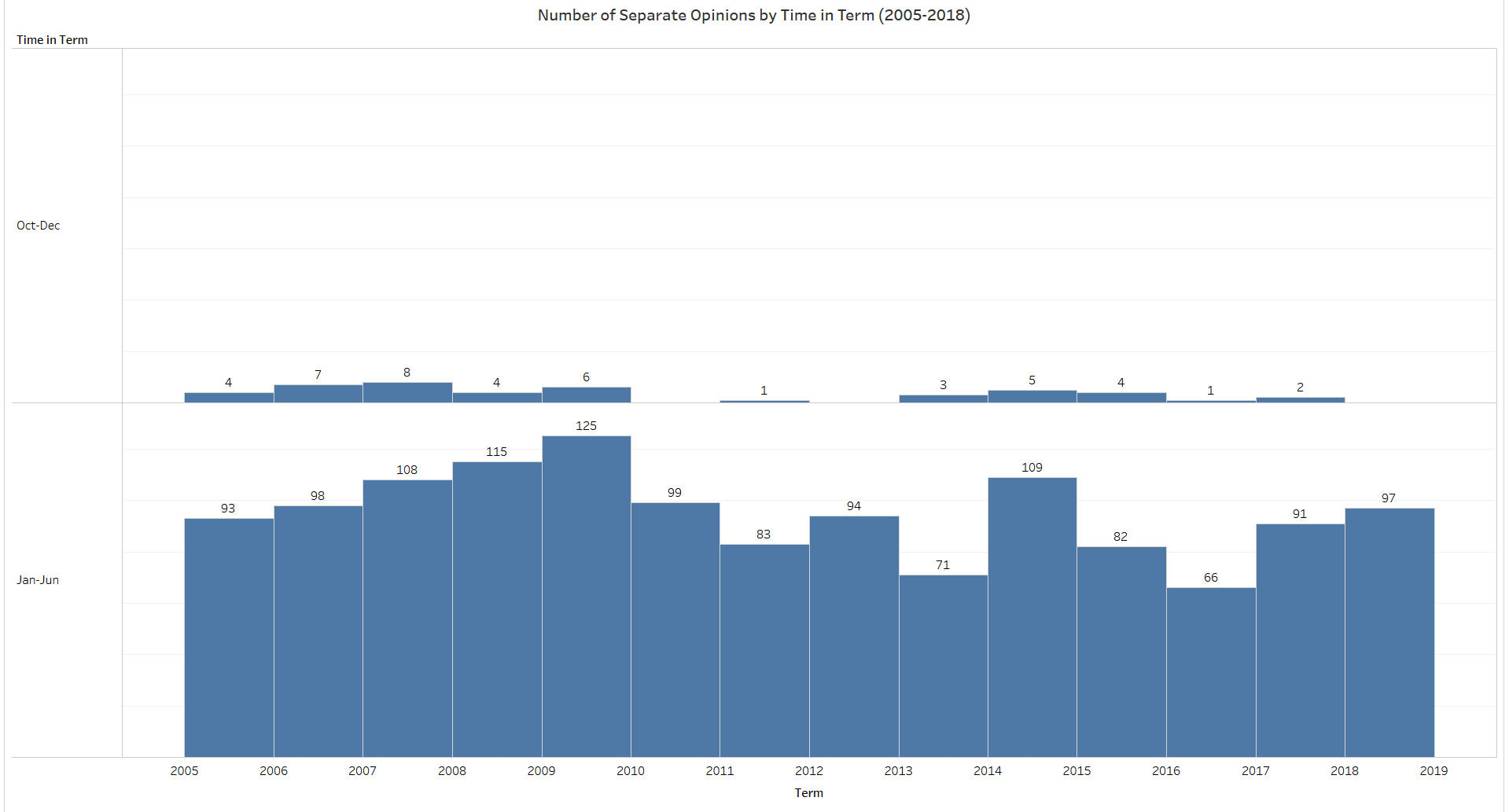

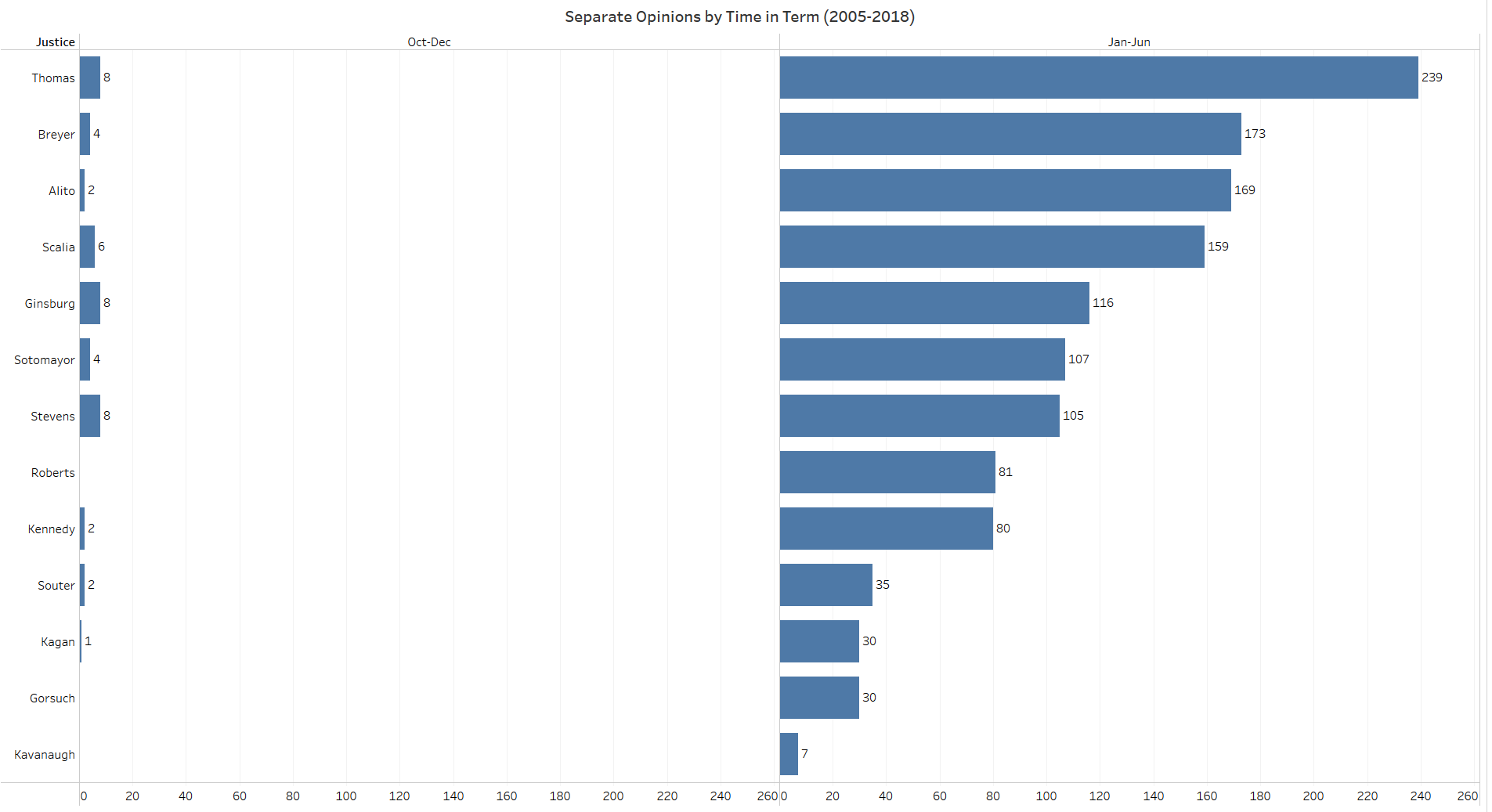

Separate opinions like Ginsburg’s dissent are entirely discretionary. The justices concur and dissent much more frequently later in terms, but there is some variation among justices in this practice.

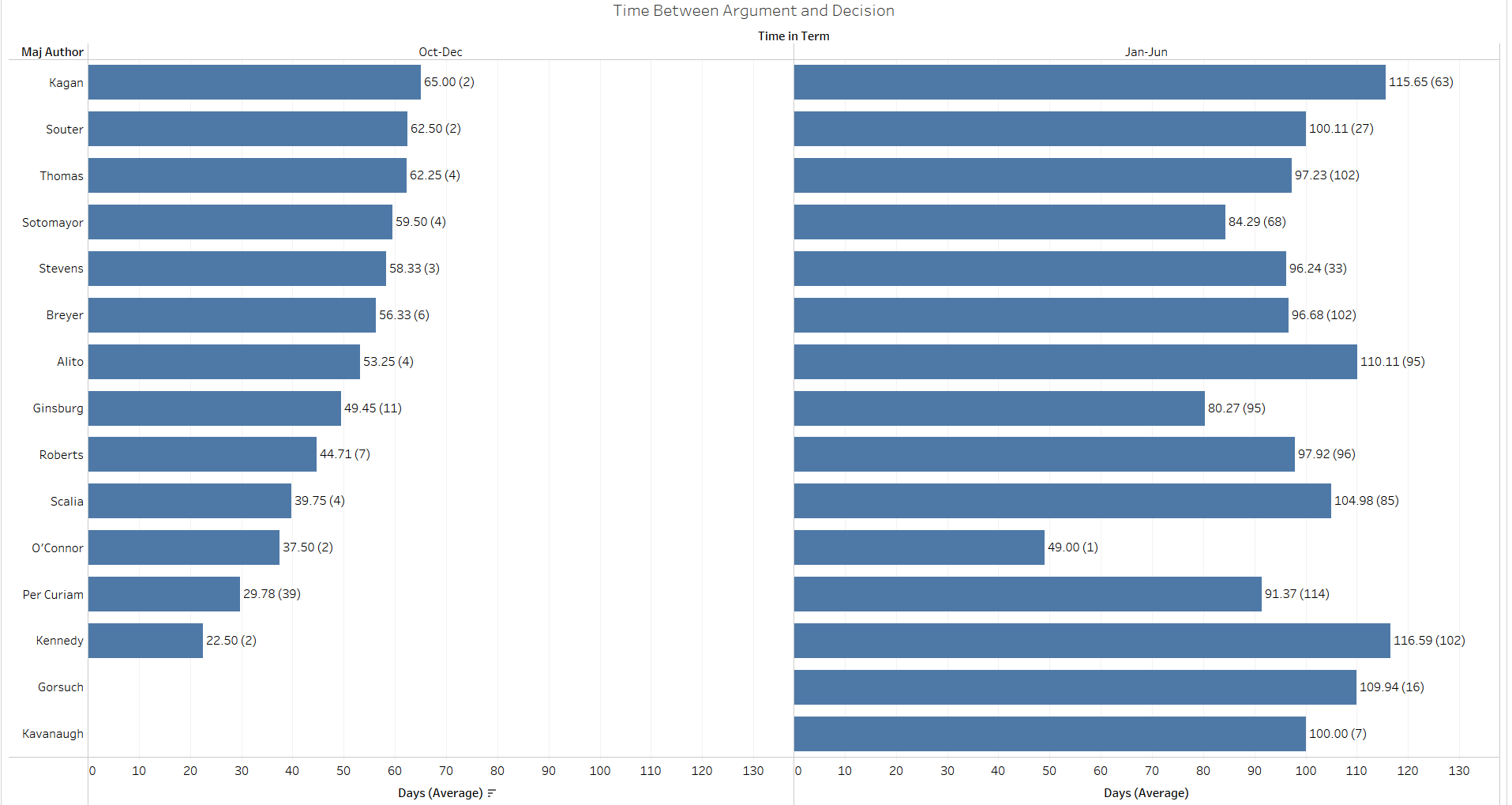

Some justices, including the most recent additions to the court, have yet to file a separate opinion between October and December of a term. One reason for this discrepancy in the number of separate opinions early and late in terms has to do with the time the justices take to come to their decisions. There just is not that much time between October and December, and so the justices often take more time between arguments and decisions later in the term. We can see differences when examining by majority author (the first numbers are the average amount of time, and the numbers in parentheses are the number of decisions these average times are based on).

Every justice took less time between argument and decision in the October-December period than they did between January and June. Some justices’ differences, like those for Justice Anthony Kennedy, are quite extreme, while others, like those for Ginsburg and Justice Sonia Sotomayor, are significantly less so.

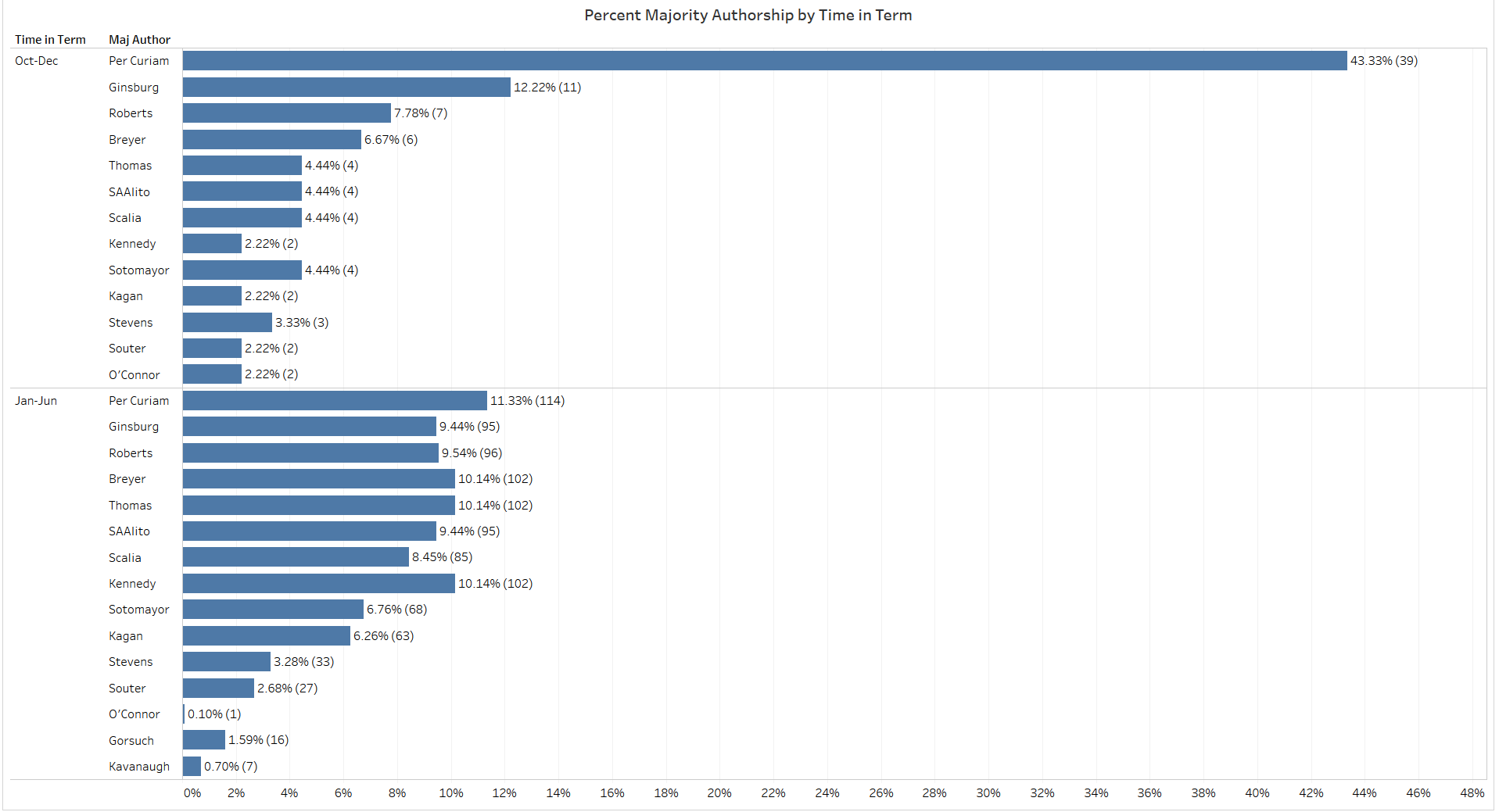

Focusing on the justices, some are also more active majority-opinion authors early in terms than others.

The numbers indicate the percentage of the total number of majority opinions authored by each justice between October and December and between January and June from the 2005 through the 2018 terms. Most opinions early in the term are unsigned (and known as per curiam decisions). Unsigned decisions comprise 30 percent less of all later-term decisions relative to signed opinions. Ginsburg is the only justice with over 10 percent of the early-term opinions. She also authored almost five percent more of the early-term opinions than the next justice, Chief Justice John Roberts. Neither of the newest justices on the court, Justices Neil Gorsuch or Brett Kavanaugh, has yet written a majority opinion between October and December of a term (including during the 2019 term).

Even though the justices write fewer separate opinions at the beginnings of terms, some justices are more active in this regard than others.

Justice Samuel Alito, for instance, authored only one percent of his separate opinions in the early months of a term, and Justice Clarence Thomas authored just three percent of his. Ginsburg, by contrast, wrote over six percent of her separate opinions between October and December of the 2005-2018 terms.

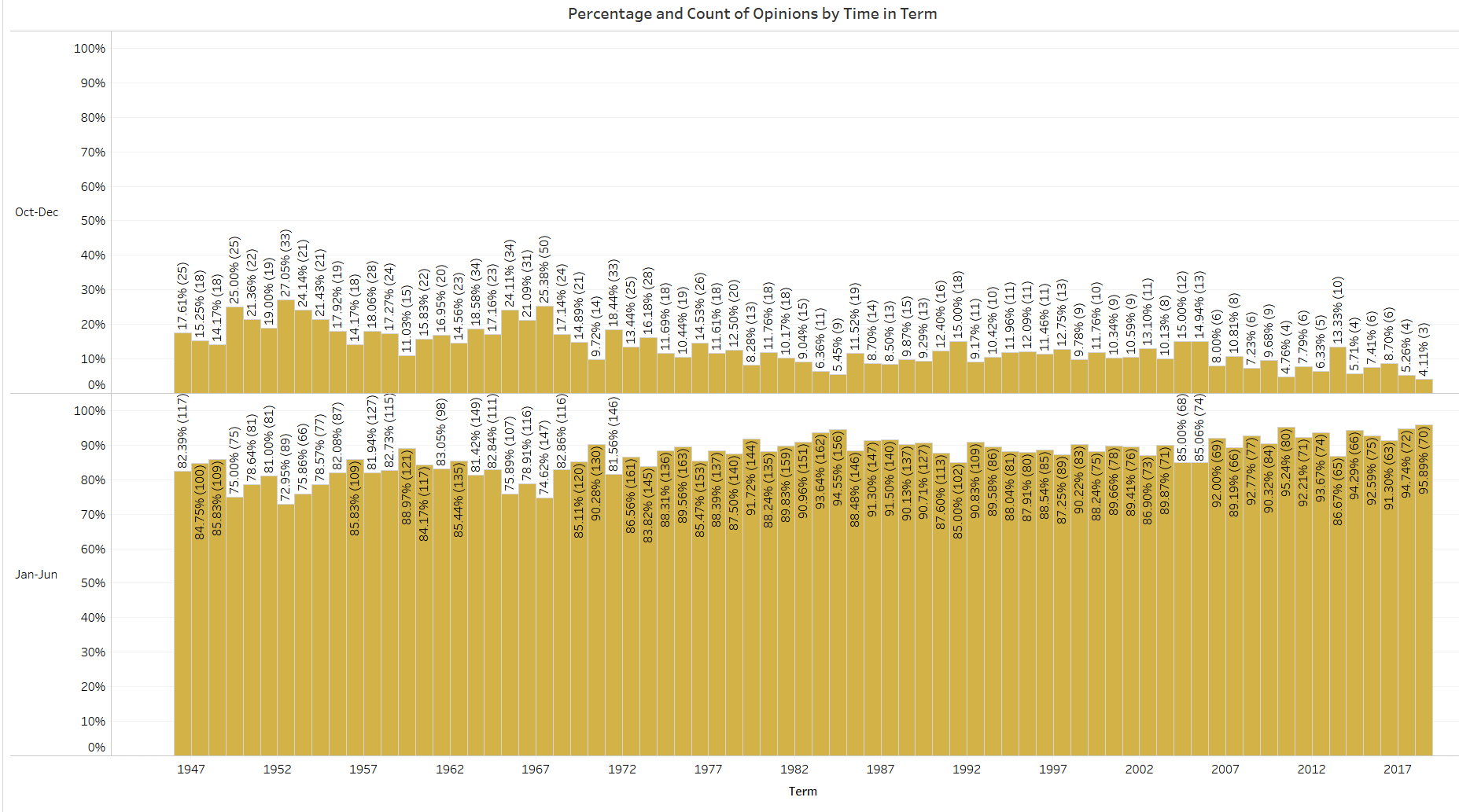

Looking across the history of the modern court, even though the justices’ total majority-opinion output has declined precipitously over time, their production has declined more early in terms relative to later in terms. Although the number of majority opinions released each term has diminished from over 150 to between 60 and 70, the relative number of opinions released in October through December compared to January through June has declined as well.

In the past several terms, the justices have only released three to six opinions before the new calendar year. This accounted for less than 10 percent of the court’s majority-opinion output in each of these terms and was a far cry from the 50 majority opinions released between October and December in the 1967 term, which constituted over 25 percent of the court’s output that term.

With three opinions released in the first few months of the 2019 term, the court is on pace with its past several terms. Sotomayor and Thomas wrote the two signed opinions (the third opinion was unsigned), and Ginsburg filed the lone separate opinion. Although this might seem like a slow start to the term, it appears to be a reflection of the justices’ needing more time to reach nonunanimous decisions. Looking forward to the next several terms, it will be interesting to see whether other justices will author signed majority opinions early in a term or whether this will remain a practice relegated primarily to only certain justices on the court.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.