Empirical SCOTUS: How Gorsuch’s first year compares

on Apr 11, 2018 at 12:00 pm

In 1986, when Justice Antonin Scalia joined the Supreme Court, the bench looked quite different than it does today. In fact, none of the justices on that court still sits on the Supreme Court bench. In 1986 the court was composed of five justices who were predominantly ideologically conservative and four justices who were predominantly liberal. Now, one year after Justice Neil Gorsuch joined the court and over two years since Scalia’s death, the landscape is quite different. Not only is there a changed set of faces on the court, but there are changed dynamics between the justices, and new dominant personalities. This post reflects on the impact Gorsuch has made on the court’s decision-making and looks back to compare this with the changing dynamics when the other sitting justices and Scalia joined the court.

Gorsuch

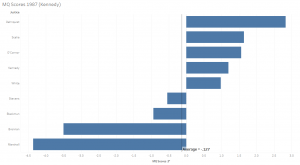

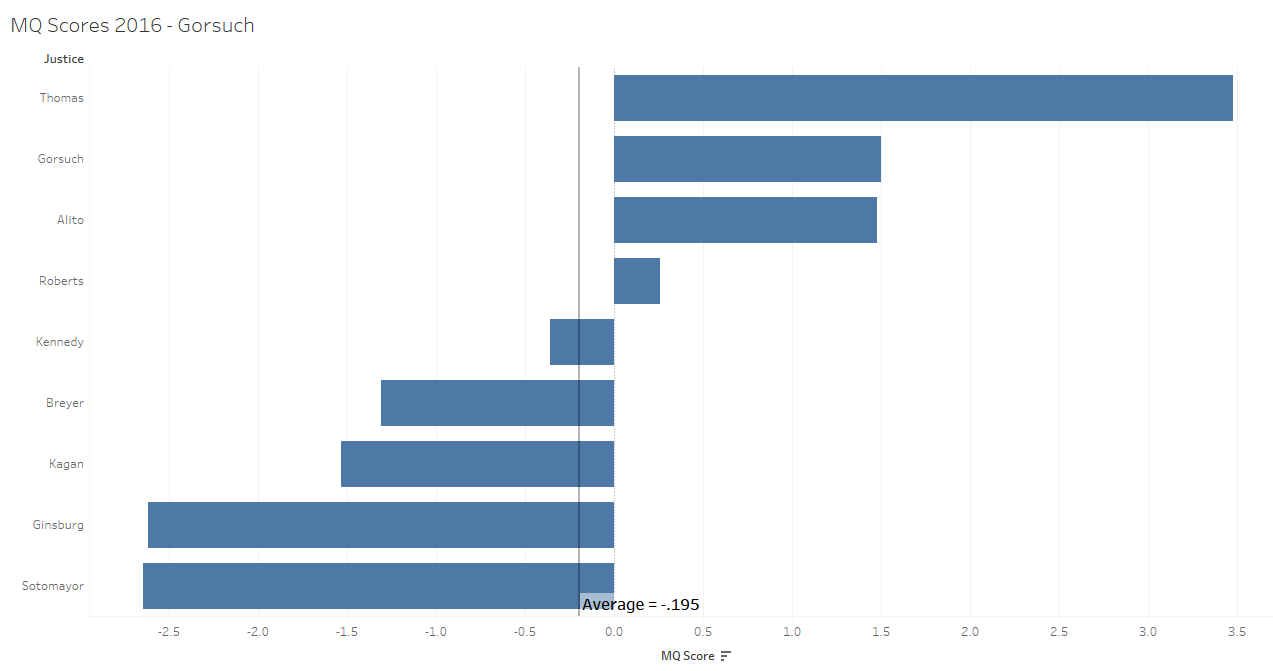

Gorsuch joined the Supreme Court at a unique time. Although there is much discussion about how this court could be the moving toward the right, especially if Justice Anthony Kennedy (or any of the more liberal justices) retires with a Republican president at the helm, other statistics show that the court at present is actually more ideologically liberal than it has been in years. According to the Martin-Quinn Scores, the ideological metric commonly used to measure the relative positions of Supreme Court justices, at the end of last term the court was the only one in recent memory with five primarily liberal justices and four predominantly conservative justices (in the graph below, scores greater than zero denote conservatives, and scores of less than zero denote liberals). The justices’ scores at the end of the 2016 term, Gorsuch’s first partial term on the court, look as follows:

Not only does Kennedy’s score from the 2016 term place him as the fifth liberal justice, but the average score across all justices also is in liberal territory. With over 30 decisions under his belt, Gorsuch has now shown that he is a worthy conservative successor to Scalia. According to the scores from the end of last term, Gorsuch was the second most conservative justice on the Supreme Court after Justice Clarence Thomas. This position was helped by the fact that Gorsuch voted alongside Thomas in every decision Gorsuch participated in last term.

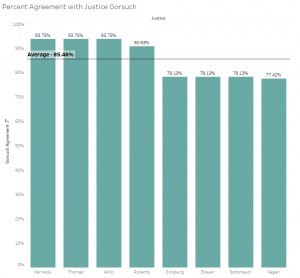

Although Gorsuch has not continued to vote alongside Thomas in every instance, he has in most. The next figure shows Gorsuch’s voting alignment with the other justices on the court through his first 30 votes relating to slip opinions. (The actual number of votes is 32, because his 30th vote was given on the same day as two other votes.)

Through this set of decisions, Gorsuch voted the same way as Kennedy, Thomas and Justice Samuel Alito each 93.75 percent of the time. Gorsuch’s alignment with Chief Justice John Roberts is close behind, with an alignment of 90.63 percent, while none of the more liberal justices have above 80 percent agreement with Gorsuch. Gorsuch’s average agreement percentage of 85.46 percent is right in the middle of those for the other justices. Within the set of Gorsuch’s first 32 votes, he dissented six times, wrote four majority opinions and authored three dissents. Seventy-five percent of these decisions (24 of 32) were unanimous.

Scalia

Looking back to when Gorsuch’s predecessor joined the court, we see a very different set of justices on the bench. The ideological balance of the court according to MQ Scores at the end of the 1986 term, Scalia’s first on the court, looks as follows:

Like Gorsuch, Scalia was the second most conservative justice according to these scores at the end of his first term. Only Chief Justice William Rehnquist ranked more conservative. Although the average ideological score was also negative, this was due to the highly negative scores of Justices William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall. Unlike the lay of the land when Gorsuch joined, the court had a clear five-justice conservative majority at the end of Scalia’s first year.

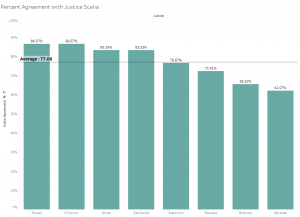

At 77.08 percent, Scalia’s average agreement score from his first 30 votes is a quite a bit lower than Gorsuch’s. The difference between Scalia’s alignment with the more conservative justices and the somewhat liberal Justice Harry Blackmun, for instance, is not particularly stark. This can be compared with the large degree of difference in Scalia’s votes from those of Marshall, even at the outset of Scalia’s tenure on the court.

Scalia authored two majority opinions and one dissent across his first 30 votes. Within this set, he dissented three times. Ten of the first 30 votes he participated in were decided by a unanimous court.

Kennedy

Kennedy joined the court in the following term — 1987 — when it was substantially similar in composition to when Scalia was confirmed.

Over his first term, Kennedy was the fourth most conservative justice and had a very similar score to that of his predecessor, Justice Lewis Powell, in Powell’s final years on the court.

Kennedy had a higher average agreement rate across his first 30 votes than Scalia.

Although Kennedy aligned more closely with the more conservative justices at the time, he voted in the same direction as the predominantly liberal Brennan 90 percent of the time through this set of cases. Just as he does now, Kennedy had a high level of agreement with most justices when he joined the court in the 1987 term. Kennedy only dissented once across his first 30 votes and didn’t author a single dissent in those instances. He did author two majority opinions within this set, and 23 decisions out of his first 30 votes were decided by unanimous votes.

Thomas

By the time Thomas joined the court in the 1991 term, the balance of the justices was tipped further in the conservative direction.

Only Justice John Paul Stevens and Blackmun were liberal holdouts at this point. The court’s average MQ Score at this time was well into conservative territory at .733. As the only one who was the most conservative justice in his first term on the court, Thomas is unique among the justices examined in this post.

Thomas’ average agreement with the other justices was above that for Scalia, but below that for Kennedy.

Across his first 30 votes, Thomas agreed in almost every instance with Scalia. This level of agreement was even higher than that for Thomas and Gorsuch across Gorsuch’s first 30 votes. There is large variation in Thomas’ agreement rates, as the range spans from 96.67 percent, with Scalia, to 66.67 percent, with Stevens. Thomas dissented four times across his first 30 votes and was the only justice among the ones discussed in this post to author a solo dissent in his set. He wrote three total dissents as well as five majority opinions in these cases. Twenty of the first 30 decisions reached after Thomas joined the court were achieved through unanimous votes.

Ginsburg

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg helped move the Supreme Court back in a liberal direction, even though her ideology score was only slightly liberal in her first term on the court.

The court was still predominantly conservative when Ginsburg joined, and the average MQ Score was also in conservative territory.

Ginsburg had one of the higher levels of agreement with the other justices across her first 30 votes.

With an average of 87.81 percent agreement, Ginsburg had over 90 percent alignment with the more conservative Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and Rehnquist. Ginsburg had her lowest alignment with Blackmun, at 76.67 percent.

Ginsburg had a unique first 30 voting decisions (31, actually, because two were made on the same day after her 29th vote). She authored more decisions in her first set than any of the other justices discussed, with 10, all majority opinions. This is now not surprising, given Ginsburg’s continued efficiency at writing opinions. She was also the only justice described in this post to vote only in the majority in each of her first 30-odd votes. Seventeen of her first 31 votes were made in unanimous decisions.

Breyer

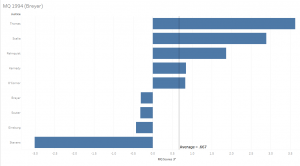

Justice Stephen Breyer joined the court the year after Ginsburg was confirmed. When Breyer joined, the ideological makeup of the court was predominantly conservative, as it had been the previous year, and so was the average MQ Score across justices.

Breyer was the fourth most liberal justice. according to his MQ Score at the end of his first term. By this point, Ginsburg had already dropped to the second most liberal justice on the court. The average across justices, however, was well into the conservative zone at .667, with Thomas still holding the position as the most conservative justice.

Breyer’s voting alignment with the other justices was below that for Ginsburg across his first 32 votes.

Surprisingly, Breyer’s lower average alignment score of 81.91 percent was brought down the most because of his lack of alignment with the most liberal member of that court, Stevens. Breyer’s alignment with Thomas was also on the low end, while he had a high degree of alignment with Ginsburg and Kennedy.

Across his first 32 votes, Breyer dissented twice, while authoring three majority opinions and one dissent. Thirteen of these 32 decisions were made by unanimous votes.

Roberts and Alito

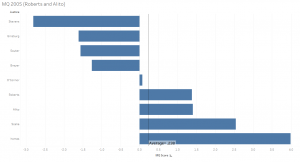

Roberts and Alito both joined the court during the 2005 term, although Roberts joined at the beginning of the term and Alito joined several months later. Both justices turned out to be very reliable conservative votes.

These justices’ MQ Scores at the end of the 2005 term were quite similar to one another and placed them as the third and fourth most conservative justices on the court. The court still had a 5-4 conservative balance at the time, although only slightly, because O’Connor had slipped to an almost neutral position by her final term in 2005.

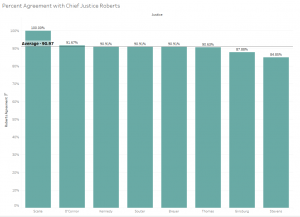

Roberts and Kennedy were the only two justices to average over 90 percent alignment across justices during their first 30 votes (33 for Roberts, because he had multiple votes on the same day as his 30th) on the court.

Roberts was one of only two justices in this post to have 100 percent alignment with another justice during his first set of votes. This high level of alignment was between Roberts and Scalia. Note that not even Thomas and Gorsuch aligned this strongly across Gorsuch’s first 30 votes on the court. Roberts shared over 90 percent of the same votes with the more liberal Breyer and Souter and only slightly below 90 percent with the even more liberal Ginsburg and Stevens.

Across his first 33 votes, Roberts only dissented once. He also only authored two opinions, both majorities with no authored dissents. Twenty-five of Roberts’ first 33 decisions were decided by unanimous votes.

Alito, who joined the court later in the 2005 term, had a lower average alignment with other justices, at 84.8 percent.

Alito also had a clearer distinction in his alignment with the more conservative and liberal justices: His alignments with the four more liberal justices all fell below his average, while his alignments with the four other conservative justices all were above his average alignment rate.

Across his first 34 votes, Alito dissented twice, although he did not author any of these dissents. He did author five majority opinions during this time. Twenty-two of his first 34 votes were decided by unanimous decisions.

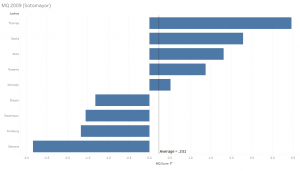

Sotomayor

By the time Justice Sonia Sotomayor joined the court, the justices were moving into more liberal territory.

According to her MQ Score, Sotomayor was the third most liberal justice by the end of her first term – more liberal than Breyer, while less liberal than Ginsburg and Stevens.

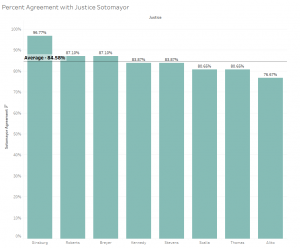

Sotomayor’s average voting alignment with other justices across her first 31 votes was quite similar to that of Gorsuch.

Aside from Sotomayor’s high alignment with Ginsburg, Sotomayor actually aligned next closely with the more conservative Roberts. Sotomayor shared the fewest number of votes with Alito.

Although Sotomayor dissented four times across her first 31 votes, she did not author any of these dissents. She did, however, author three majority decisions in this set. Nineteen of the first 31 decisions that Sotomayor voted on were decided by unanimous votes.

Kagan

When Justice Elena Kagan joined the court, she became the fourth strong liberal vote. At this time, though, Kennedy still voted predominantly alongside the more conservative justices, and this helped prop up the average MQ Score for the 2010 term.

Kagan’s average voting alignment with the other justices across her first 31 votes was just below Sotomayor’s, at 83.87 percent.

There is a clear distinction between Kagan’s alignment with the more liberal justices, who are all above her average alignment level, and with the conservative justices, who all fall at or below her average level of voting alignment.

Along with Roberts’ alignment with Scalia during his first term, Kagan is the only other justice to have 100 percent alignment with another justice during a first term. In Kagan’s case, this close alignment was with Sotomayor.

Concluding thoughts

So what does all of this portend for the court moving forward? We are still judging Gorsuch on only his first set of decisions, because he has yet to finish his first full term as justice. So far, though, Gorsuch appears the conservative bastion that many hoped he’d be. As the second most conservative justice on the court at the end of his first partial term, Gorsuch may fight Thomas for the position of the court’s most conservative justice in this and subsequent terms.

Over his first year on the court, Gorsuch has clarified who he is as a justice. Gorsuch, however, filled a conservative justice’s seat. Any significant shifts in the court’s decision-making, therefore, will likely occur if President Donald Trump gets to make another nomination to the Supreme Court and if next time a more liberal justice is the one to depart. Because Kennedy has been tracking in the liberal direction over the past several terms, moving a staunch conservative justice into Kennedy’s seat could drastically shift the court’s ideological tenor.

This post was originally published on Empirical SCOTUS.