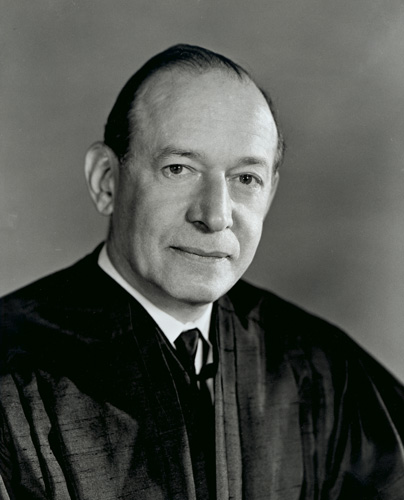

More to Fortas than scandal – Timothy Huebner on a justice “made in Memphis”

on Feb 15, 2018 at 2:59 pm

There are two primary biographies of Justice Abe Fortas — Bruce Allen Murphy’s 1988 “Fortas: The Rise and Ruin of a Supreme Court Justice” and Laura Kalman’s 1992 “Abe Fortas: A Biography.” Neither of these works devotes much attention to Fortas’ life in his hometown of Memphis, Tennessee.

Murphy – writing after the discovery of President Lyndon Johnson’s papers relating to Fortas, which Johnson ordered destroyed but which his staff secretly preserved – focused on Fortas’ downfall as a result of ethical scandals that surfaced during and after his nomination for chief justice. Kalman wrote a more comprehensive work, but still gave Fortas’ Memphis life only six pages before turning to his time at Yale Law School.

In a recent article in the Journal of Supreme Court History, “Memphis and the Making of Justice Fortas,” Timothy Huebner fills that void in historians’ understanding of Fortas’ early life. Through research in archives at Memphis public libraries, Temple Israel in Memphis, local newspapers, the University of Memphis and Rhodes College (where Huebner teaches and which Fortas attended when it was known as Southwestern), Huebner provides history that “none of us have gotten” before, as Kalman wrote in an email.

Huebner’s new research presents a different side to this man, who “grew up in an immigrant Jewish family of modest means in Memphis,” but who is “often portrayed as a consummate Washington insider,” as Huebner writes.

Huebner argues that experiences and relationships in Memphis “helped to shape some of Fortas’s specific attitudes about law and justice.” In particular, Huebner focuses on the Tennessee roots of Fortas’ approach to three constitutional values – justice for the poor, freedom for religious minorities and civil rights for African-Americans – that “have been obscured by the ethical scandals that ended his brief tenure on the Court.”

Huebner’s approach – focused on biographical more than doctrinal history of the Supreme Court – has marked his entire career as a scholar. For Huebner, any study of constitutional law “has to come with an understanding that law is shaped by institutions made up of individuals with their own backgrounds and experiences,” he said in an interview. To understand Chief Justice John Marshall, he explained, one needs to know that Marshall’s interest in a strong national government was shaped in part by fighting for American independence alongside General George Washington at Valley Forge.

In an interview, Fortas biographer Murphy said that Huebner’s insights into Fortas’ early life – including the future justice’s popularity, involvement in college affairs and close relationships with mentors – “fills in a lot of gaps and explains the man later involved in the culture of the White House” as a “close friend” of Johnson’s. For Murphy, the question of Fortas’ “rule-bending” remains open; he posited that it rested in Fortas’ association with New Deal politics. However, that inquiry was outside the scope of Huebner’s analysis, which sought simply to root some of Fortas’ jurisprudence in his early life experiences.

Justice for the poor: Gideon v. Wainwright

In this unanimous 1963 decision, the Supreme Court “held that the right to counsel was included among the rights incorporated by the Fourteenth Amendment to apply to the states.”

Fortas argued the case for the prevailing defendant, Clarence Gideon, at the request of the Supreme Court. As Anthony Lewis, author of the famous book on this case, “Gideon’s Trumpet,” wrote at the time in the New York Times Magazine, Fortas’ “oral argument was as thorough, as dramatic, as suave and—most important to the Justices—as well-prepared as anything that could have been done for the best-paying corporate client.”

Huebner argues that the poverty Fortas experienced as a child “affected Fortas’s ideas about protecting the legal rights of the poor and marginalized.” A 1991 study by sociologists E. Digby Baltzell and Howard G. Schneiderman, “From Rags to Robes: The Horatio Alger Myth and the Supreme Court,” found that up to that point, Fortas and Justice Thurgood Marshall were the two most “underprivileged” justices in history.

Huebner also suggests that “perhaps Fortas knew that in 1917, during his childhood, Memphis had established the first public defender east of the Mississippi River, only the third public defender office in the nation at the time.”

Freedom for religious minorities: Epperson v. Arkansas

In this 1968 decision, the Supreme Court held that an Arkansas statute forbidding the teaching of evolution violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment. As Fortas wrote in the opinion, “It is clear that fundamentalist sectarian conviction was and is the law’s reason for existence.”

Huebner writes that Fortas concluded his opinion “by citing not the words of the Arkansas statute, but the Tennessee statute under which Scopes had been convicted” in the famous Scopes Trial. “Growing up Jewish in Memphis during the 1920s—a fundamentalist place at a fundamentalist time”—”influenced his view of the appropriate place of religious doctrine in public policy,” Huebner argues.

As Huebner notes, Memphis newspapers had praised the conviction of John Scopes, and the city’s political boss, Edward Hull Crump, had advocated banning Clarence Darrow from Tennessee. Fortas’ first college debate as a freshman was a mock trial about the teaching of evolution.

Huebner reports that the “Justices were united in wanting to strike down the statute,” but not as a violation of the establishment clause. Fortas “took the lead” in grounding the court’s ruling against the government in that constitutional provision. As he wrote to a clerk who advised that the court not grant the case, “I’d rather see us knock this out.”

Civil rights for African-Americans: Brown v. Louisiana

In this 1966 decision, the Supreme Court “struck down as a violation of the First Amendment a Louisiana breach of peace statute that had been used against African-American civil rights protesters in a public library.” Huebner writes that Fortas also “voted with the majority in cases upholding the Voting Rights Act, striking down the poll tax, and advancing the desegregation of public schools.”

Huebner maintains that “Fortas’s experiences of seeing segregation and racial oppression in Memphis affected his outlook on matters of racial justice and civil rights.”

Throughout his career Fortas spoke out against racial injustices. In a 1946 speech in Memphis at his alma mater, Southwestern, eight years before Brown v. Board of Education and 18 years before the first black student enrolled in the college, he told a white audience, “It seems to me that our domestic problem and specifically the problem of the South must also be dealt with … We must realize that in this country of ours the democratic and constitutional promises of happiness are not the exclusive possessions of a few. They are the rights of all.”

As Fortas would write more explicitly in a 1972 op-ed in the New York Times, “as a Southerner—born and brought up in the Mississippi Delta—I recall the outrages of the Ku Klux Klan, directed against Jews, Catholics, and Negroes.”

Freedom of speech

Gideon, Epperson and Brown v. Louisiana do not represent the only areas of the law in which Fortas exerted some influence, although they are the cases Huebner said he found most rooted in Fortas’ early life experiences. Fortas was also involved in landmark rulings involving the freedom of speech. In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, Fortas wrote an opinion holding that students wearing armbands did not lose First Amendment rights to free speech at school. Kali Borkoski reported for this blog on a lecture about this case given by Kelly Shackelford at the Supreme Court in 2013.

In discussing what would happen to Justice Antonin Scalia’s unfinished opinions after the justice’s sudden death two years ago, Steve Wermiel wrote for this blog (as Murphy did in his biography) that “one of the most important free speech rulings in the Court’s history,” Brandenburg v. Ohio, “originally belonged” to Fortas before he left the bench. Justice William Brennan “used most of the opinion that Fortas had prepared, but he revised the most important part, the First Amendment test,” and released the opinion as an unsigned, per curiam decision.