Argument preview: How specific must “clearly established” law be to support federal habeas relief?

on Jan 5, 2016 at 5:17 pm

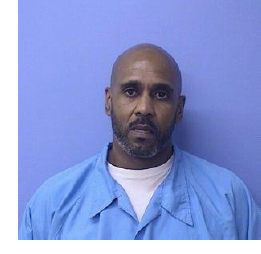

At first blush, Duncan v. Owens, a case in which the Supreme Court is set to hear oral argument next Tuesday, looks like just another example of a federal appeals court giving insufficient deference under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) to a state trial court in reviewing a state prisoner’s habeas conviction — a sin for which the Sixth Circuit alone has already been chastised by the Justices twice this Term. But this is not your routine habeas case. Instead, the real question this case raises is just how specific the Supreme Court’s “clearly established” law must be in order to provide the basis for post-conviction relief under AEDPA. Needless to say, how the Justices answer that question could have significant implications for all federal habeas review.

- Background

In November 2000, respondent Lawrence Owens was convicted for the murder of Ramon Nelson after a bench trial outside of Chicago. Although two eyewitnesses testified at the trial, there were serious inconsistencies in their testimony, and at the end of the parties’ closing arguments, the trial judge concluded that:

I think all of the witnesses skirted the real issue. The issue to me was you have a seventeen year old youth on a bike who is a drug dealer [Nelson], who Larry Owens knew he was a drug dealer. Larry Owens wanted to knock him off. I think the State’s evidence has proved that fact. Finding of guilty of murder.

As Judge Richard Posner wrote for a unanimous Seventh Circuit panel, “That was all the judge said in explanation of his verdict, and it was nonsense. No evidence had been presented that Owens knew that Nelson was a drug dealer or that he wanted to kill him . . . or even knew him — a kid on a bike.” In other words, the trial court apparently adjudicated Owens’s guilt based upon a fact not only unproven at trial, but for which no evidence whatsoever had been submitted.

Nevertheless, a divided panel of the Illinois Court of Appeals affirmed Owens’s conviction. Although the state appellate court agreed that “there was no evidence presented that defendant knew Nelson was dealing drugs, and there was no evidence presented that defendant was involved with gangs or the illegal drug trade,” it concluded that any constitutional error had been harmless beyond a reasonable doubt because one of the (inconsistent) eyewitness identifications was sufficient to establish Owens’s guilt. The Illinois Supreme Court denied Owens’s application for discretionary review, and the federal district court denied his habeas petition — on largely the same grounds as the majority of the state intermediate appellate court.

On appeal, the Seventh Circuit reversed. As Posner explained, “The trial judge hadn’t actually said that he’d considered only evidence not in the trial record, but the only ground for his finding Owens guilty that he mentioned had no basis in that record (or elsewhere for that matter).”

The Seventh Circuit then turned to AEDPA’s highly deferential standard, which only allows habeas relief if the state court decision was “contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States.” Relying on the Supreme Court’s decisions in Holbrook v. Flynn, Taylor v. Kentucky, and Estelle v. Williams, the Seventh Circuit concluded that “there’s no question that the right to have one’s guilt or innocence adjudicated on the basis of evidence introduced at trial satisfies that exacting standard.”

As for the harmless-error determination by the Illinois Court of Appeals, the Seventh Circuit emphasized the significance of the weakness of the eyewitness identifications: “Given that the entire case pivoted on two shaky eyewitness identifications, Owens might well have been acquitted had the judge not mistakenly believed that Owens had known Nelson to be a drug dealer and killed him because of it.” Under Brecht v. Abrahamson, the court concluded, the trial court’s error unquestionably had a “substantial malign influence on the verdict.” The state of Illinois, through Warden Stephen Duncan, timely petitioned for certiorari, and the Supreme Court granted review.

- Arguments

Not surprisingly, the parties’ briefs focus heavily on what, exactly, the Supreme Court’s decisions in Holbrook, Taylor, and Estelle clearly establish. The state’s brief, for example, emphasizes that the Supreme Court “has never held that a trial judge’s inferences regarding motive, which is not an element of the crime of murder, is a violation of a criminal defendant’s right to due process, even if those inferences are not directly established by the trial evidence.” Thus, the state argues, the Seventh Circuit “violated [the] Court’s unmistakable admonition against framing the issue at too high a level of generality when determining whether there is clearly established law,” by relying on cases that raised materially different facts. Moreover, and in any event, the harmless-error determination by the Illinois Court of Appeals was not itself unreasonable, the state contends, because “[t]here was ample evidence before the court, including eyewitness identifications and [Owens’s] flight from police, that [Owens] committed the murder.” That conclusion is bolstered, the state concludes, by the deference AEDPA mandates to factual findings made by state courts under 28 U.S.C. § 2254(e)(1) — including, in this case, the determination by the Illinois Court of Appeals that one eyewitness’s testimony was reliable.

Owens, in contrast, argues that the principle of Holbrook, Taylor, and Estelle is not too general, but rather makes clear that “habeas relief may be granted where a trial court bases a finding of guilt on facts not in evidence,” and other decisions demonstrate that “motive is a key means of establishing whether a particular person committed a crime where identity is at issue.” In other words, although Holbrook, Taylor, and Estelle didn’t present precisely the same factual scenario (in which a trial judge entered a verdict in a bench trial based upon facts not in evidence), they do support the conclusion, as Posner wrote for the Seventh Circuit, “that a judge or a jury may not convict a person on the basis of a belief that has no evidentiary basis whatsoever.” As for the harmless-error determination by the Illinois Court of Appeals, Owens echoes the Seventh Circuit’s argument that it was unreasonable under Brecht because the state appellate court simply “substitut[ed] its view of the credibility of the eyewitnesses for that of the trial court,” and thereby “had the effect of improperly supplanting the trial court as arbiter of witness credibility and primary fact-finder.” As for AEDPA’s mandate of deference to factual findings, Owens argues both that (1) the state waived that argument by not raising it in the Seventh Circuit or in its cert. petition; and (2) in any event, the harmlessness determination by the Illinois Court of Appeals was a legal determination, and not a factual finding, and thus not covered by Section 2254(e)(1).

- Conclusion

How closely divided the Justices are on the “merits” question presented in this case — whether it was clearly established by Holbrook, Taylor, and Estelle “that a judge or a jury may not convict a person on the basis of a belief that has no evidentiary basis whatsoever” — may become clear from the focus of next Tuesday’s argument. If there is no consensus on the Court in one direction or the other on that question, then the Justices may well gravitate toward the state’s harmless-error argument — even though it appears, at least based on the briefs, to be somewhat weaker than its argument on the merits. The upside of a decision focused on harmless error, though, is that it would allow the Court to side with the state (and its twenty-seven sister states who filed as amici curiae in support), without issuing a broader ruling about whether state-court errors must be factually identical to those errors “clearly established” to be unconstitutional.