SCOTUS FOCUS

The rise of certiorari before judgment

on Jan 25, 2022 at 5:44 pm

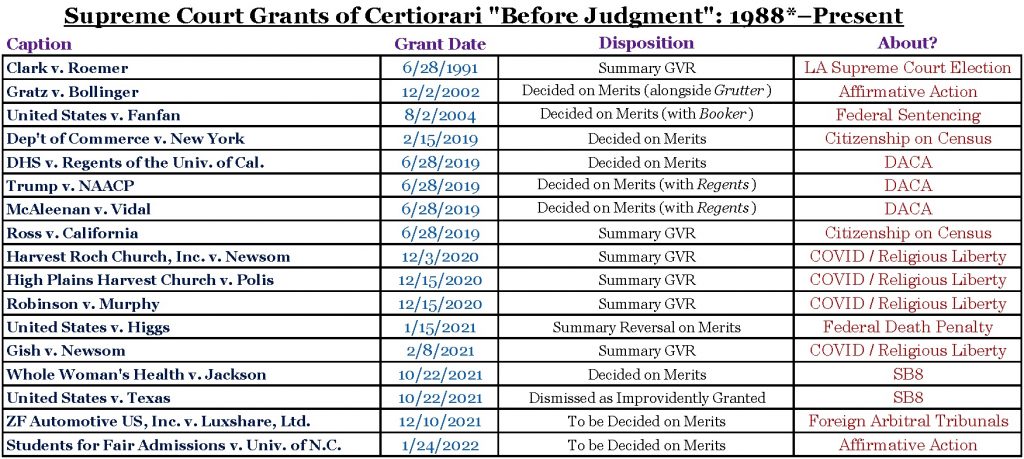

For obvious reasons, the Supreme Court’s decision on Monday to grant certiorari in a pair of cases challenging race-based affirmative action in higher education drew major headlines. Less well noticed was a curious procedural feature of the second case, Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina. Unlike the Harvard University case, in which the same petitioner, Students for Fair Admissions, is asking the Supreme Court to reverse a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit, the UNC case seeks review directly of a district court’s decision — invoking the Supreme Court’s statutory power to grant certiorari “before judgment” in the federal courts of appeals. Indeed, Monday’s grant was the 14th time the justices have granted cert before judgment since February 2019, after having gone more than 14 years without granting it once. Cert before judgment is on the rise, and it’s not at all clear why.

Since Congress first conferred such authority as part of its far broader expansion of certiorari jurisdiction in the Judiciary Act of 1925 (the so-called “Judges’ Bill”), the Supreme Court has used its power to grant “cert before judgment” sparingly. As the current version of the court’s Rule 11 emphasizes, cert before judgment will be granted “only upon a showing that the case is of such imperative public importance as to justify deviation from normal appellate practice and to require immediate determination in this Court.” The leading Supreme Court treatise, Supreme Court Practice, reinforces the rarity of such relief: “The public interest in a speedy determination must be exceptional … to warrant skipping the court of appeals in this fashion.” The most well-known examples prove the point — from the Nazi saboteurs’ case during World War II; to the Youngstown steel seizure case in 1952; to the Watergate tapes case in 1974; to the Iranian hostage dispute in 1981. In all of those cases, not only were the questions presented of the utmost importance, but time was of the essence, as well.

The justices would occasionally grant cert before judgment in less significant cases that were companions to “ordinary” cert petitions raising similar issues, but even then, the court would often go years in between uses of the obscure procedure. Thus, starting in 1988 (when, as part of broader reforms to the court’s docket, Congress eliminated the ability to directly appeal to the Supreme Court district court decisions striking down state or federal statutes), the practice became all but moribund. Between the passage of the 1988 reforms and August 2004, the Supreme Court granted cert before judgment only three times — once to expeditiously vacate and remand a district court ruling in an election dispute based upon an intervening ruling by the justices in a related case; and twice to bring companion cases to the court alongside “ordinary” grants of certiorari (in the Michigan affirmative action cases in 2003 and in the constitutional challenge to the Federal Sentencing Guidelines in 2004). And from August 2004 through February 2019, the court did not grant a single petition for cert before judgment (in United States v. Windsor, the constitutional challenge to the Defense of Marriage Act, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit ruled in between when the Obama administration sought cert before judgment and when the court granted cert).

Research by Steve Vladeck. Dataset begins with 1988 amendments to Supreme Court’s jurisdiction. “GVR” = grant, vacate, and remand.

Just as noteworthy during this period were some of the denials of cert before judgment. In June 1998, for instance, the justices denied Independent Counsel Ken Starr’s two petitions for cert before judgment in discovery disputes arising out of the Whitewater investigation (petitions on which future Justice Brett Kavanaugh was co-counsel). And the court also denied cert before judgment in one of the first disputes to reach the justices from Florida in the aftermath of the 2000 presidential election. In each case, although the dispute was critically important and time was of the essence, the court had faith that lower courts would move quickly — expressly noting as much in the Whitewater denials.

It’s against that backdrop that the uptick in cert before judgment since February 2019 is eye-opening. Counting the UNC affirmative action case, eight of the 14 grants were argued or set for argument (including three that were consolidated in the 2020 ruling on the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program), and a ninth was held for, and summarily resolved after, the 2019 ruling on whether a citizenship question could be asked on the 2020 census. In other words, by the end of this term, the court will have used cert before judgment to conduct plenary review of six different disputes in three years — at a time when it is conducting plenary review of fewer cases overall than at any point since the Civil War. Although it is possible to make the case that cert before judgment was warranted in at least some of these cases, it is difficult to see how it was warranted in all of them — especially given the high bar that the court has historically applied for bypassing ordinary appellate review.

The other five grants were disposed of through novel procedural orders — four to set aside district court rulings in light of intervening shadow docket rulings on emergency applications (the first instances I’ve ever found of such a use of cert before judgment); and a fifth to summarily resolve a federal death penalty dispute one week before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit was scheduled to hold argument (and, perhaps more relevantly, five days before President Joe Biden was set to come to office). As I’ve written at some length elsewhere, this may be the most troubling feature of the uptick in cert before judgment — using a tool that was meant to expedite merits review of cases of national importance to summarily wipe away lower-court rulings of more modest significance without any of the benefits of plenary review.

But whether viewed as a feature or a bug, it can no longer be denied that the current court’s unprecedented use of cert before judgment is a fact. And although only the justices can know for sure why it has become such a common practice in the last three years, a couple of possibilities stand out. First, the increasing use of cert before judgment could be a way of mitigating the number of major rulings the court is handing down through emergency orders. For instance, in the challenges to Texas’ anti-abortion law, known as S.B. 8, cert before judgment allowed the court to reach the merits of the dispute with remarkable dispatch, unencumbered by the doctrinal and prudential constraints on emergency relief (such as they are). Thus, extraordinary relief might be a means of avoiding emergency relief — where the culprit is the broader pressures being placed on the court to act at the outset of most major contemporary legal disputes (or, depending upon one’s perspective, the justices’ increasing willingness to move quickly).

Second, the increasing use of cert before judgment could reflect unspoken hostility toward particular courts of appeals; of the 14 grants since 2019, eight have come from just three circuits: the 2nd (which had two), the 4th (also two), and the 9th (which had four). Third, and related, it is of course possible that the shift in the court’s composition since 2018 has likewise had both procedural and substantive implications for the justices’ willingness to use cert before judgment — perhaps reflecting a shift in the majority’s understanding of what satisfies the onerous criteria of Rule 11, and a change in the willingness of a majority of the justices to rely on more unorthodox procedural mechanisms. As with the rising frequency of emergency relief, perhaps grants of cert before judgment make subsequent grants seem less extraordinary.

But whatever the cause, as with the rise of grants of emergency relief, it would certainly behoove the justices to say a bit more about why cert before judgment has become so much more common. After all, if Rule 11 doesn’t mean what it used to mean, and if courts of appeals can be bypassed even in cases that aren’t of both the utmost national importance and temporal urgency, then it would certainly help if the parties — and, even more importantly, the lower courts — were clued in.