Empirical SCOTUS: The hottest bench in town

on Sep 25, 2018 at 2:56 pm

The practice of Supreme Court oral arguments has changed dramatically over time. Once multi-day events, Supreme Court oral arguments now typically take place in a one-hour time span, with some exceptions granted by the justices. Not only has the time allotted to arguments changed, but so has the justices’ engagement. This increased engagement has helped quantitative scholars of the court understand the relationship between oral arguments and votes both in the aggregate and in particular cases.

One claim that has been raised time and again over the years is that Justice Antonin Scalia changed the tenor of oral arguments and specifically gave rise to the “hot bench” of justices who ask many questions. This claim was recently framed a bit differently during Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee by Supreme Court advocate and former Solicitor General Paul Clement, who said, “I think the Supreme Court right now is about the hottest bench that the Supreme Court has ever been. I think each of the last justices that have been confirmed by this committee has tended to ask more questions than the justice they replaced.” This post tests these claims on data from Supreme Court oral arguments.

Scalia helped transform Supreme Court oral arguments. There is ample and detailed empirical support for this proposition in a recent book chapter by political scientists Tim Johnson, Ryan Owens and Ryan Black. But have all of the most recently confirmed justices asked more questions than the justices they replaced? Thoroughly answering this question involves putting the justices under a microscope.

The data used to test this claim come from 90 oral argument transcripts across five court terms. This includes 10 from 1965, 20 from 1979, 20 from 1989, 20 from 1999, and 20 from 2017. (Transcripts from the Oyez Project were used for all years prior to 2017.) This set of arguments encompasses years from all current justices and their most recent predecessors. It allows for a look before and after Scalia joined the court in 1986. Finally, data from the 1965 term helps to set a baseline from the Warren court years. The selection of arguments within a term was random aside from those in the 1965 term, which were randomized among arguments that lasted one hour.

The aggregate

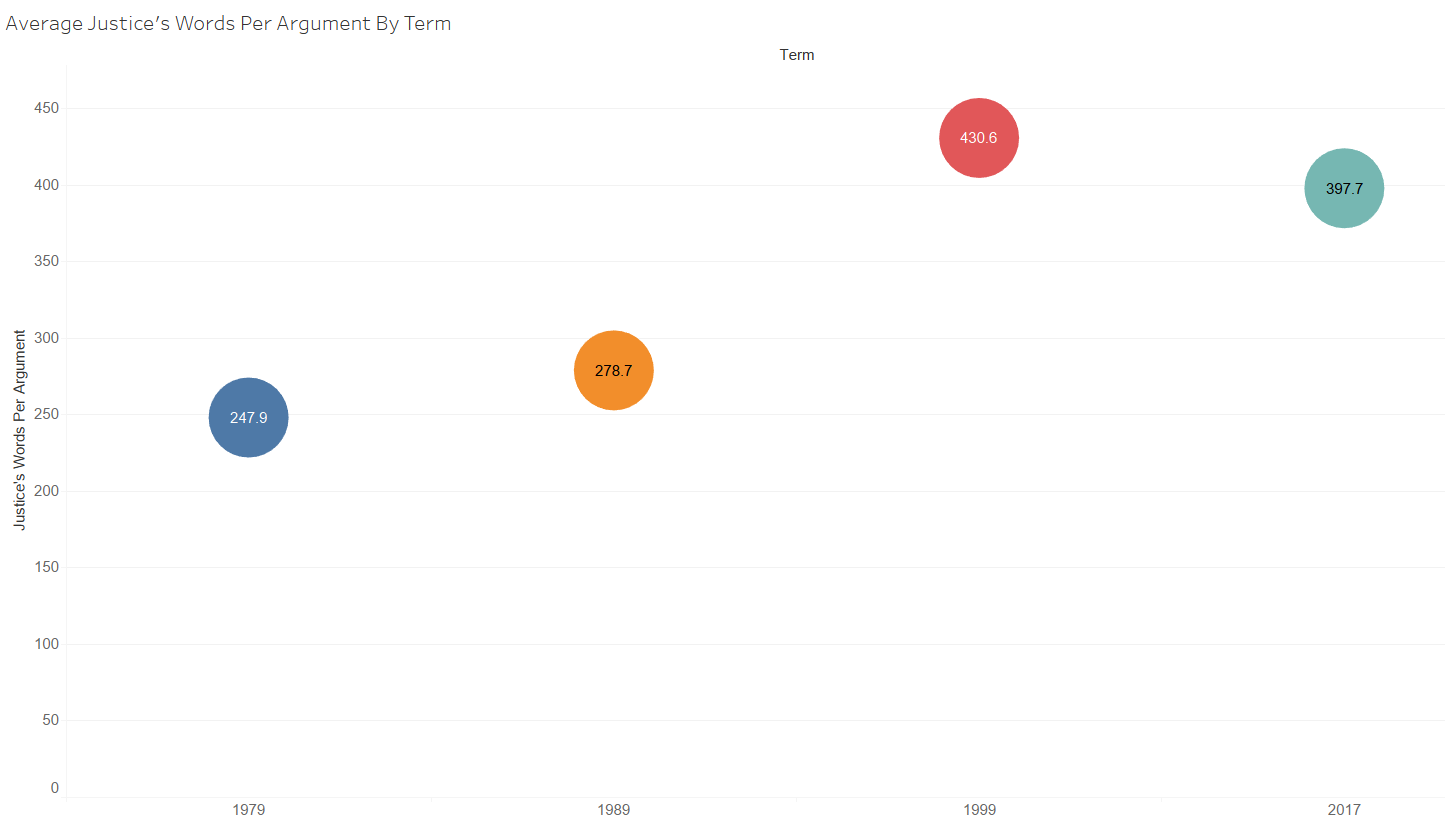

All of the current justices are fairly engaged in oral arguments with the exception of Justice Clarence Thomas. An increase in engagement is evident at both the aggregate court level and by individual justice. If we look at average words per justice per argument by term in these samples, there is an increase from 1979 through 1999 and then a slight dip in 2017 (The numbers for 1999 and 2017 are sufficiently close that the difference could be a factor of sampling.).

When we reframe this to look at justices’ words per talking turn, this measure increases in each subsequent term.

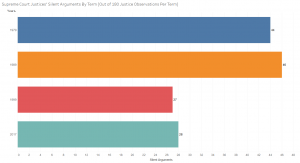

The justices have found techniques like increasing the number of words per utterance that allow them to say more during arguments. The change in level of engagement is also evident in the number of arguments when justices were silent in each set from 1979, 1989, 1999 and 2017.

Even with Thomas’ silence in all 20 argument slots for the 1999 and 2017 terms, the sum of silent-justice slots in these two terms is well under the 44 from 1979 and 46 from 1989. This reflects a change in the court’s culture, as is detailed in the chapter from Johnson, Owens and Black, which can likely be ascribed to Scalia.

Individual justices

Breaking this down into individual actors, we can see a much more balanced spread of justices silent at oral arguments in the terms preceding 1999.

Justices William Brennan, Harry Blackmun, Lewis Powell and Thurgood Marshall each were silent for multiple arguments in the 1979 and/or 1989 terms. When we push back to 1965, a full 42 percent of the 90 justices’ argument slots were silent, including all 10 from Justices William Douglas and John Marshall Harlan.

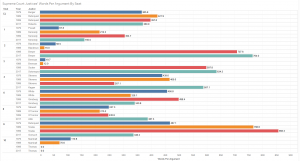

With silence decreasing over time, the justices’ words per argument increased. The justices were much less talkative in the 1965 term than they were in any of the subsequent terms measured for this post.

Only Justice Abe Fortas was in the range of average words per justice per argument for a modern justice. When we look by the justices’ seats we also see that the justices generally said more in the more recent terms.

[Note: Seat ordering follows historic Supreme Court seating and the numbering accounts for previously abolished seats.]

Of the more recent justices, only Justice Neil Gorsuch, Chief Justice John Roberts and Thomas spoke less than their predecessors. Gorsuch replaced Scalia, who was very active in oral arguments, so this dip is not surprising. Thomas is widely acknowledged for his idiosyncratic and almost complete silence at oral arguments since he joined the court. Roberts’ words per argument are in the same vicinity as those of Rehnquist, and because this is only based on a sample of arguments, the difference is insignificant at best.

When we look at actual questions per justice/argument in the transcripts (delineated by question marks), we can see that the increase over time is not quite as universal.

Along with Thomas, Gorsuch and Roberts, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asked fewer questions on average than Justice Byron White, and Justice Elena Kagan asked fewer questions than Justice John Paul Stevens.

The justices’ average utterances per argument by seat follow a similar path.

By utterance we also see that although Justice Samuel Alito took a similar number of talking turns on average as Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, he was well behind Justice Potter Stewart in this category.

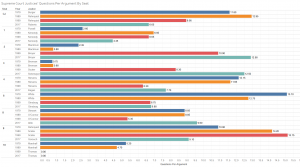

The most evident across-the-board increase in verbosity among justices is in their words per utterance. The modern justices aside from Gorsuch and Thomas each surpassed their predecessors in this respect.

Conclusion

In the same vein as described in the chapter from Johnson, Black and Owens, these data allude to interesting changes in oral argument dynamics, especially when compared to the court before Scalia joined in 1986.

Focusing once again on Clement’s comments, the current justices tend to speak more than their predecessors, although this is not the case across the board. An upward trajectory in contemporary justices’ talking turns and questions per argument as compared to their most recent predecessors is less evident. The justices do appear more strategic in their talking now as compared to the past: On average, they utter more words each time they speak.

Even though according to these metrics, Gorsuch is not more active than Scalia, the justice who fills Justice Anthony Kennedy’s spot on the court very well may exceed Kennedy in oral argument engagement. Kennedy averaged fewer words than the average justice in the samples for each of the 1989, 1999 and 2017 terms. It is entirely plausible that the next justice on the court will have at least as much to say as the average justice, especially because there is a significant dip in average words per argument after those of Kagan and Justices Stephen Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.