Argument preview: Interpretation of removal statute raises deference questions

on Apr 16, 2018 at 1:32 pm

Pereira v. Sessions is not the immigration case that everyone will be watching this month, but it is definitely worth a glance. At first blush, this case looks like a hyper-technical and relatively dull issue of statutory interpretation. But looks are deceiving. Not only does the case have potentially far-reaching implications for many immigrants, but it will also give the justices another chance to stake out their views on what deference to agencies under Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. requires.

The case concerns a statutory provision enacted in 1996, when Congress amended the Immigration and Nationality Act in sweeping ways. Overall, these amendments made it much easier for a noncitizen to trigger potential deportation consequences and much harder for noncitizens – including long-time lawful permanent residents – to obtain discretionary relief from deportation. Under pre-1996 law, in about 50 percent of cases in which an immigrant was otherwise deportable, immigration judges opted to allow the immigrant to remain, issuing a form of relief called suspension of deportation, which required the immigrant, among other things, to demonstrate seven years of continuous presence. Some immigrants reached the seven-year mark over the course of the deportation proceedings.

In 1996, Congress substantially expanded the grounds of deportation and simultaneously replaced suspension of deportation with a much narrower form of relief called “cancellation of removal.” Cancellation serves the humanitarian purpose of giving otherwise removable immigrants a chance for mercy. There are two forms of cancellation. The first is available to individuals with five or more years of lawful permanent residence and seven or more years of total continuous physical presence in the United States. The second form of cancellation, at issue in this case, is available to noncitizens with 10 or more years of continuous physical presence in the U.S., regardless of legal status, provided the individual meets other stringent requirements. To prevent immigrants from trying to run up the clock on continuous presence by delaying removal proceedings, the clock on continuous physical presence stops at the earlier of either the time the government serves the noncitizen with a statutorily defined notice to appear, or the time the noncitizen commits certain acts – not at issue in this case – that make them deportable on enumerated crime or security grounds.

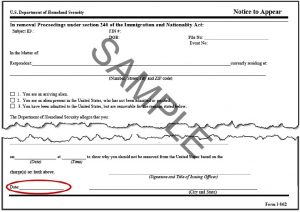

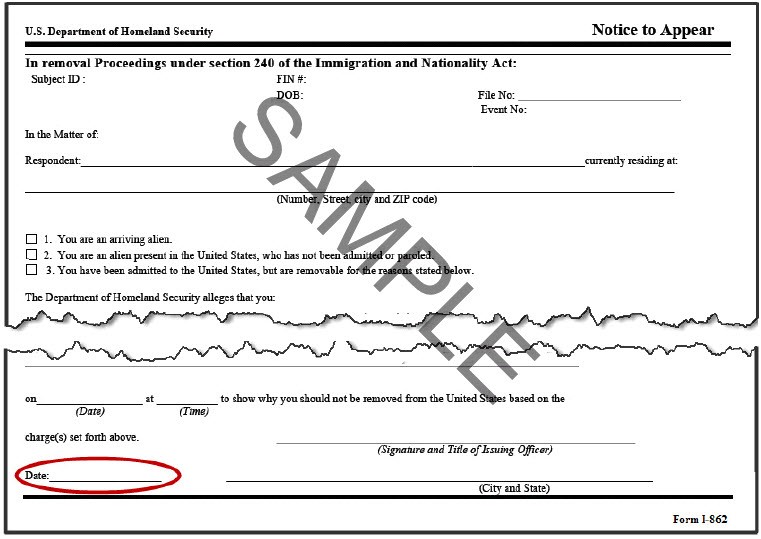

Wescley Pereira entered the United States on a six-month visitor’s visa in June 2000. He did not leave when his visa expired, which rendered him removable under the INA. In May 2006, the Department of Homeland Security served him personally with a form entitled “Notice to Appear.” The NTA indicated that DHS was seeking to remove him for overstaying his visa and ordered him to appear for removal proceedings in the Boston immigration court “on a date to be set at a time to be set.” The question before the Supreme Court is whether this NTA stopped the clock on Pereira’s accrual of continuous physical presence for purposes of cancellation.

In relevant part, the stop-time rule in 8 U.S.C. § 1229b(d)(1) reads as follows: “For purposes of this section, any period of continuous residence or continuous physical presence in the United States shall be deemed to end … when the alien is served a notice to appear under section 1229(a).”

Section 1229(a), in turn, reads:

Notice to Appear

(1) In general In removal proceedings …, written notice (in this section referred to as a “notice to appear”) shall be given in person to the alien … specifying the following:

…

(G) (i) The time and place at which the proceedings will be held.

The NTA that Pereira received in May 2006 did not specify the time at which the proceedings would be held. Pereira argued that the NTA therefore did not stop the clock on his accrual of continuous physical presence for purposes of cancellation. The government took the opposite position, and the Immigration Judge in Pereira’s removal proceeding agreed with the govenment, ruling that the omission of a date and time certain from the notice to appear did not “somehow … negate the service of the Notice to Appear insofar as it would cut off continuous physical presence.” The Board of Immigration Appeals affirmed the IJ’s decision, relying on its 2011 precedential decision in In re Camarillo, in which the board reasoned that “an alien’s period of continuous physical presence for cancellation of removal is deemed to end upon service of the Notice to Appear even if the Notice to Appear does not include the date and time of the hearing.” The board concluded that Section 1229b(d)(1)’s overbroad cross-referencing of 1229(a) – rather than a narrower reference to the list of NTA requirements in 1229(a)(1) – indicated that Congress did not intend to incorporate any of the requirements of section 1229(a) into the NTA issued under section 1229b(d)(1).

On appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit employed the two-step deference framework established in Chevron. Under that framework, a court must first determine whether a statute is ambiguous; if so, the court should defer to an administrative agency’s reasonable interpretation. The 1st Circuit found the statute in this case ambiguous, and therefore proceeded to Chevron step two, asking whether the court should defer to the BIA’s interpretation. The panel concluded that such deference was warranted because the board’s reading was “better” than Pereira’s. The court of appeals noted that the cross-referenced statutory provision – Section 1229(a) — has procedural requirements that could not be included in an NTA, that Pereira’s interpretation would cause administrative difficulties, and that the board’s reading is supported by legislative history.

Before the Supreme Court, Pereira argues that deference to the board was inappropriate because the stop-time rule unambiguously requires the NTA to include all of the requirements of Section 1229(a), including the time of the hearing. There is certainly support for that position in the statutory language. The government’s position, however, is that the stop-time rule’s cross-reference to “section 1229(a)” creates ambiguity because there are aspects of section 1229(a) that do not deal with the content of the NTA at all. Congress could easily have referenced subsection 1229(a)(1) if it meant to incorporate the subsection’s requirements, and indeed did so in other places in the immigration statute. Indeed, because Congress included in subsection 1229(a) not just a list of the required elements of an NTA but also provisions on how to change the hearing date, “there is no reason to assume that Congress intended the omission of a date certain in the original notice to be fatal.” In support, the government cites to loosely comparable reasoning in cases involving notices to appeal.

Pereira argues that the fact that the cross-referenced Section 1229(a) includes subsections with information about how to amend a properly issued NTA does not negate the express requirements in Section 1229(a)(1) as to what the NTA must contain. Pereira’s argument that the statute unambiguously supports his position seem reasonably strong. But most circuits to consider the question have accepted the government’s argument that the overinclusive cross-reference generates ambiguity.

To the extent the text is susceptible to alternative interpretations, Pereira maintains that the court could and should have used all of the accepted tools of statutory construction, including the legislative history and appropriate canons of construction, to give effect to Congress’ intent as embodied in the statute before proceeding to Chevron step two. Pereira notes that Congress enacted the NTA provision in question to replace an older provision in which two separate hearing notices were required. The 1996 amendments to the statute eliminated the two-step notice process and replaced it with a consolidated notice process. The legislative history explains that the point of this change was to make the removal process more efficient. Such efficiency, Pereira and several amici curiae who filed briefs supporting his position assert, appears to be undermined by DHS’s reversion in regulation and practice to a two-step process.

The government, in contrast, argues that certain aspects of the legislative history, including 1997 legislation that allowed pre-1996 “orders to show cause” to suffice in lieu of NTAs for purposes of the stop-time rule, suggest that Congress had a more flexible view of the NTA. The government also argues that its interpretation of the statute advances Congress’ primary purpose in enacting the stop-time rule, namely, to stop noncitizens from gaming the removal process by dragging out proceedings to extend their time in the United States. The amicus brief for the American Immigration Lawyers Association and the Immigrant Defense Project responds that although this is indeed the purpose of the stop-time rule, Pereira’s interpretation of the statute is consistent with this purpose. There is no question of Pereira dragging out proceedings in this case. The statute is clear that an immigrant’s accrual of continuous physical presence stops when the government issues the notice to appear. The question here is different: What makes an NTA statutorily sufficient for purposes of the stop-time rule?

Pereira and his amici also invoke the well-known maxim that ambiguous statutory provisions that could result in deportation must be construed in favor of the noncitizen. Given the high stakes in removal proceedings, the Supreme Court has, in the past, applied this kind of rule – similar to the rule of lenity in criminal cases — in immigration proceedings, for example in the 1948 case Fong Haw Tan v. Phelan. Arguably, this runs up against deference to the agency in ways that are difficult to reconcile. The amicus brief for the National Immigrant Justice Center thus makes the pitch that the maxim should be applied at the first step of the Chevron analysis as part of the process of construing the statute, before courts find ambiguity and defer to the agency. The government responds that Pereira has “identified no case in which that interpretive tool of last resort was dispositive in rejecting an agency’s construction under Chevron.”

Ultimately, then, the Supreme Court could use this case not only to decide the appropriate application of Chevron deference to Pereira’s situation, but also to weigh in again on broader questions of how courts should construe statutes in the first instance within the Chevron framework and when deference to the agency is appropriate within that framework.

[Disclosure: Goldstein & Russell, P.C., whose attorneys contribute to this blog in various capacities, is among the counsel on an amicus brief in support of the petitioner in this case. The author of this post is not affiliated with the firm.]