A “view” from the Court: Making accommodations for the deaf and hard of hearing

on Apr 19, 2016 at 4:18 pm

It’s odd to walk into the Supreme Court and see lawyers in the bar section holding iPhones, iPads, and other electronic devices during a court session. But that was the case on Tuesday as twelve members of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Bar Association were being sworn in to the Supreme Court Bar.

The group was founded in 2013, and the Supreme Court agreed to make accommodations for the group to participate in the ritual of its in-courtroom swearing-in ceremony. That included the provision of sign-language interpreters as well as a limited wi-fi signal allowing the lawyers to receive real-time translation on their electronic devices.

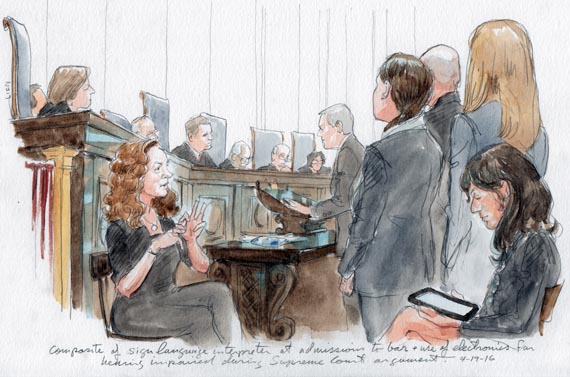

A composite with sign language interpreter and use of electronics during admissions to the bar and arguments (Art Lien)

John F. Stanton, a deaf appellate lawyer with the U.S. Department of Justice, introduced the twelve deaf or hard of hearing lawyers and followed custom by vouching for their qualifications for the Supreme Court Bar. My colleague Tony Mauro of The National Law Journal reported last week that Stanton himself used the Communication Access Realtime Translation, or CART, system when he was presented for the Court’s bar in 2005.

Once Stanton finished presenting the deaf or hard of hearing lawyers for the bar, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., moved his arm broadly into a stamping gesture, in American Sign Language, as he also proclaimed that Stanton’s motion was granted and the lawyers would be admitted. The Court’s public information office said Roberts had learned the sign specifically for the ceremony.

Mauro noted in his article that Stanton is the author of a 2011 article in the Valparaiso University Law Review, Breaking the Sound Barriers: How the Americans with Disabilities Act and Technology Have Enabled Deaf Lawyers to Succeed. Both the law review article and Mauro’s piece detail some of the Supreme Court’s past interactions with deaf lawyers, including the only time a deaf lawyer argued a case, in Board of Education v. Rowley. (That 1982 case was about a deaf student wanting a sign-language interpreter. The girl, and the deaf lawyer, lost.)

In the courtroom on Tuesday, the twelve members of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Bar Association relied on both CART and rotating sign-language interpreters, who sat in a chair just under Justice Elena Kagan’s place on the bench, facing the bar section.

The deaf and hard of hearing lawyers witnessed two opinion announcements (delivered before they were sworn in), and most stayed for the two cases being argued. Each element presented some challenges for the sign-language interpreters and the deaf or hard of hearing lawyers.

For example, Justice Stephen G. Breyer, in announcing the decision in Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt, warned that “it’s a very complicated, technical case.” He wasn’t kidding.

When Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg began delivering the opinion in the second decision of the day, Hughes v. Talen Energy Marketing LLC, she said, “In terms of complexity, I top the case that Justice Breyer just announced.” She wasn’t kidding, either.

The first case, United States v. Bryant, presented the question of whether reliance on valid, uncounseled tribal-court misdemeanor convictions to prove a federal statute’s predicate-offense element violates the Constitution.

The second case, Universal Health Services v. United States ex rel. Escobar, dealt with whether the “implied certification” theory of legal falsity under the False Claims Act is viable, and what that may mean for a government contractor’s reimbursement claim.

In the second case, in particular, the sign-language interpreter had to think quickly to offer interpretations of such legal or idiosyncratic terms and phrases such as “the restatement of torts,” “hornbook law,” “Chevron on steroids,” and “the dog that didn’t bark.”

Justice Breyer referred his old teacher of contracts, “Blackjack Dawson.” And Roy T. Englert Jr., representing a Massachusetts health provider in the second case, repeatedly used the Biblically inspired phrase “every jot and tittle.”

Despite such challenges, what was evident by the end of the morning was a group of deaf and hard of hearing lawyers had a clear understanding of two hours’ worth of Supreme Court proceedings. Or, at least as clear as anyone else in the Courtroom.