9750 Words on Elena Kagan

on May 8, 2010 at 1:00 am

Below, we discuss the most significant aspects of Elena Kagan’s experience and writings as they relate to the Supreme Court. We also consider various criticisms that have been raised against Kagan, including with respect to her views on the military (supposedly too liberal) and executive power (supposedly too conservative), as well as the prospect that she will be required to recuse from a substantial number of cases early in her tenure on the Court. We separately discuss the specific votes she likely will receive for and against her confirmation. Each separate section below is identified by its author(s).

Our goal is to provide information for the public to make its own judgments, and we also offer opinions on certain claims made about her. We do not discuss the reasons I think the President is most likely to appoint her, which are discussed in earlier posts. But in general, here are the highlights:

Kagan is uniformly regarded as extremely smart, having risen to two of the most prestigious positions in all of law:Â dean of Harvard Law School and Solicitor General.

In government and academia, she has shown a special capacity to bring together people with deeply held, conflicting views. On a closely divided Supreme Court, that is an especially important skill.

Conservatives who she has dealt with respectfully (for example, Charles Fried and former Solicitors General to Republican Presidents) will likely come forward to rebut the claim that she is an extreme liberal.

She would also be only the fourth woman named to the Court in history, and President Obama would have named two. At age 50, she may serve for a quarter century or more, which would likely make her the President’s longest lasting legacy.

As with John Roberts, her service in a previous presidential Administration exposed her to a number of decisionmakers, who have confidence in her approach to legal questions.

The fact that she lacks a significant paper trail means that there is little basis on which to launch attacks against her, and no risk of a bruising Senate fight, much less a filibuster.

And finally, one point is often overlooked: Kagan had some experience on Capitol Hill and significant experience in the Executive Branch, not only as an attorney in the White House counsel’s office, but also as an important official dealing with domestic affairs. She has thus worked in the process of governing and does not merely come from what has recently been criticized (unfairly, in my view) as the “judicial monastery.â€

Summary Biography [by Tom Goldstein]

Elena Kagan was born on April 28, 1960 in New York. She attended Hunter College High School, Princeton (graduating in 1981), and Harvard Law School (graduating in 1986).

Kagan clerked for Judge Abner Mikva of the D.C. Circuit, then for Justice Thurgood Marshall in the Court’s 1987 Term.

Upon completing her clerkship, in 1988, Kagan went to work as an associate at Williams & Connolly in Washington, D.C.

In 1991, Kagan joined the law faculty of the University of Chicago. She principally taught administrative and constitutional law. During this period, she met Barack Obama, who was also teaching at the law school.

In 1993, Kagan temporarily served as special counsel to Senator Joe Biden (then-Chairman of the Judiciary Committee) during the confirmation process of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She then returned to teaching at Chicago.

In 1995, Kagan joined the Clinton Administration. Initially, she served as Associate White House Counsel. In 1997, she was named Deputy Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy and Deputy Director of the Domestic Policy Council.

In 1999, President Clinton nominated Kagan for a judgeship on the D.C. Circuit. She never received a hearing, however.

In 1999, Kagan returned to academia, accepting a position on the law faculty at Harvard (initially as visiting professor, and then as a permanent member of the faculty). She principally taught administrative law, civil procedure, constitutional law, and a seminar on the presidency. In 2001, she received tenure.

In 2003, she was named the dean of the law school, succeeding Bob Clark, as well as the Charles Hamilton Houston Professor of Law. Her Harvard faculty page is here.

President Obama nominated Kagan to serve as his first Solicitor General, and she was confirmed in 2009 by a vote of 61-31.

In 2009, the President considered and interviewed Kagan for a potential nomination for the Supreme Court seat vacated by David Souter to which Sonia Sotomayor was ultimately named.

Academic Career [by Erin Miller]

Kagan has published six scholarly law review articles, all of which predate her receiving tenure at Harvard in 2001. Her earlier articles focus on First Amendment doctrine, while the last two discuss administrative law.

She has also published numerous book reviews, encyclopedia entries, and tributes to figures in the law.

In her most widely cited free speech paper, “Private Speech, Public Purpose: The Role of Governmental Motive in First Amendment Doctrine,†published in 1996 in the University of Chicago Law Review, Kagan contends that the primary purpose of courts reviewing speech restrictions should be to ferret out impermissible governmental motives–not necessarily to protect individual expression or the marketplace of ideas.

The Chicago paper builds on the arguments she made in two earlier papers on the Supreme Court’s 1992 decision in R.A.V. v. St. Paul, which struck down a city ordinance banning certain “bias-motivated†conduct. In one, she argues that when government is under no imperative to prohibit or endorse any speech, it cannot selectively do so based on the viewpoint of that speech. In the other, she argues that the Court can still regulate pornography and hate speech under her interpretation of the First Amendment.

Kagan’s 2001 article “Presidential Administration,†published in the Harvard Law Review, was named the year’s top scholarly article by the American Bar Association’s Section on Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice. Declaring an “era of presidential administration,†the paper examines how the three previous presidents exercised increasingly direct authority over federal agencies; she argues that in this way, Bill Clinton – unlike his de-regulatory predecessors – advanced his own progressive and pro-regulatory political agenda.

In a 1995 review of Stephen Carter’s book on confirmation hearings, “Confirmation Messes, Old and New,†Kagan criticized senators for failing to ask, and nominees for refusing to answer, questions about their views on specific issues.  Senators ought to dig deeply, she contended, asking straightforward questions about both the nominee’s judicial philosophy and her substantive views on constitutional issues: “The critical inquiry as to any individual similarly concerns the votes she would cast, the perspective she would add (or augment), and the direction in which she would move the institution†(934). Nominees could be asked about their views on particular issues that the Court regularly faces, such as “privacy rights, free speech, race and gender discrimination, and so forth†(936). On this view, a nominee ought to refrain only from expressing a “settled intent†to vote a particular way on a particular case that might come before her.

Links to Academic Papers:

On Administrative Law:

- 2009. “Office of the White House Counsel” in Mark Green and Michele Jolin, eds., Change for America: A Progressive Blueprint for the 44th President (Basic Books).

- 2001. “Presidential Administration,â€Â Harvard Law Review. Full text: Lexis || Westlaw

- 2001. “Chevron Nondelegation Doctrine,â€Â Supreme Court Review. PDF

On the First Amendment:

- 2000. “Libel and the First Amendment (Update),” Encyclopedia of the American Constitution, Supplement II.

- 2000. “Masson v. New Yorker Magazine, Inc.,“Â Encyclopedia of the American Constitution (entry).

- 1996. “When A Speech Code Is A Speech Code: The Stanford Policy and the Theory of Incidental Restraints,” University of California at Davis Law Review. PDF

- 1996. “Private Speech, Public Purpose: The Role of Governmental Motive in First Amendment Doctrine,â€Â University of Chicago Law Review. PDF.

- 1993. “Regulation of Hate Speech and Pornography After R.A.V,” University of Chicago Law Review. [An abbreviated version of this article appears in Laura Lederer and Richard Delgado, eds., The Price We Pay (Hill & Wang 1995).] PDF

- 1993. “A Libel Story: Sullivan Then and Now,â€Â Law & Social Inquiry (book review). PDF

- 1992. “The Changing Faces of First Amendment Neutrality: R.A.V. v. St. Paul, Rust v. Sullivan, and the Problem of Content-Based Underinclusion,â€Â The Supreme Court Review. PDF

On the Supreme Court Confirmation Process:

- 1995. “Confirmation Messes, Old and New,” University of Chicago Law Review (book review). PDF

Additional:

- 2009. “Foreword” in Daniel Hamilton and Alfred Brophy, eds., Transformations in American Legal History: Essays in Honor of Professor Morton J. Horwitz (Harvard).

- 2008. “Harvard Law Revisited,” The Green Bag. PDF

- 2007. “Richard Posner, the Judge,” Harvard Law Review. Full text on Harvard Law Review website

- 2007. “In Memoriam: Clark Byse,” Harvard Law Review. Full text on Harvard Law Review website

- 2006. “Women and the Legal Profession – A Status Report (Leslie H. Arps Memorial Lecture),” The Record.

- 2006. “In Memoriam: David Westfall,” Harvard Law Review. Full text on Harvard Law Review website

- 1993. “For Justice Marshall,” Texas Law Review.

- 1986. “Note, Certifying Classes and Subclasses in Title VII Suits,” Harvard Law Review (student note).

(Links courtesy of University of Chicago Law Review and the Supreme Court Review.)

Tenure as Dean [by Anna Christensen]

During her tenure as dean of Harvard Law School, from 2003 until her appointment as Solicitor General in 2009, Kagan spearheaded a number of significant changes to the school’s curriculum, faculty, budget, and student life, establishing herself as an immensely popular leader and garnering significant goodwill from students and faculty alike.

As dean, Kagan oversaw Harvard Law School’s “Setting the Standard†fundraising campaign, which she inherited upon her appointment. When the campaign ended in 2008, it had raised over $476 million, making it the most successful fundraising effort in the history of legal education.

Kagan also undertook a substantial effort to revise and update the law school curriculum. In particular, she introduced a new first-year curriculum to replace the one that had been in use for over one hundred years; added new legal clinics, including a Supreme Court advocacy project; and increased the school’s academic commitment to environmental law and public service.  She also added a new $150 million academic center and contributed to efforts to make Harvard Law School’s campus more environmentally friendly.

Kagan’s time as dean is perhaps best known for shifts in the composition of and relationships among the law school’s faculty (including particularly among conservatives and liberals). Despite strong opposition from certain faculty members, Kagan supported the hiring of Jack Goldsmith, a former Assistant Attorney General in the Office of Legal Counsel who at the time was criticized for his perceived role in authoring the Bush Administration’s wartime interrogation policy.  She is credited with improving faculty relations significantly, ending decades of feuding between some professors.  She also added a number of high-profile academics to the school’s faculty, often luring these professors from other prestigious law schools. And Kagan introduced a program aimed at bridging the gap between legal practice and academia by hiring practicing attorneys for associate or temporary professorships.

Among the smaller-scale changes brought about by Kagan during her tenure as dean, she is perhaps best-known for her commitment to improving student life on campus. In her first few years at Harvard, Kagan introduced free coffee and bagels for students, renovated the law school’s student center, added a multipurpose ice rink and a volleyball court, and improved the gymnasium. She explained her emphasis on these small-scale improvements as resting on her belief that “small, symbolic policies could help solve big problems.â€

The Solomon Amendment [by Tom Goldstein]

Kagan’s deanship at Harvard was marked by her role in the controversy over the University’s response to the Solomon Amendment. The relevant timeline follows.

In 1979, Harvard Law School adopted an anti-discrimination policy requiring any employer using the Office of Career Services for recruiting to sign a statement indicating that it did not discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or certain other criteria; pursuant to that policy, the law school banned military recruiters from using the Office of Career Services.

At some point between 1979 and 1992, the school permitted recruitment through a student group, the HLS Veterans Association. (That group was founded in 1985; it is possible another group was involved earlier.) Under that policy, the recruiters used the same physical facilities, but were denied recognition under the law school’s career placement processes.

In 1996, Congress passed the Solomon Amendment, which blocks federal funding for schools which refuse to allow military recruitment on campus.  The Amendment was passed in response to the refusal of many schools, including Harvard, to allow recruiters on campus on the ground that the military’s “don’t ask, don’t tell†policy violated the schools’ nondiscrimination policies.

Harvard does not appear to have changed its policy, likely regarding it as sufficient that the military was able to recruit through the student veterans group. Alternatively, the school may have concluded that it was not subject to the Solomon Amendment because the law school itself did not receive federal funding.

In 2002, the Department of Defense issued a ruling that the law school’s recruitment policy would trigger the loss of federal funding for all of Harvard University – $328 million. The law school relented by making an exception to its nondiscrimination policy and allowing the military full access to recruitment processes.

In 2003, Kagan was named dean of the law school. She maintained the existing policy.

Also in 2003, a consortium of law schools and faculty members – the Forum for Academic and Institutional Rights (FAIR) – challenged the Solomon Amendment on constitutional grounds. Although Harvard Law School was not a member of FAIR, in 2004, Kagan joined fifty-three other faculty members in signing an amicus brief in support of FAIR, but arguing that the case should be resolved on statutory grounds (as opposed to FAIR’s constitutional challenge).

In November 2004, a divided panel of the Third Circuit ruled in FAIR’s favor, but the ruling was stayed pending Supreme Court review of the case.

Immediately after the Third Circuit’s ruling, Kagan reinstated Harvard Law School’s prior policy: banning the military from using the main career office, but permitting access through the student veterans group.

The veterans group responded that it would attempt to coordinate recruitment to some extent by email, but it cautioned that it had “declined interim options to establish formal liaison relationships, sponsor regular on-campus military recruiting fairs, coordinate interviews extensively, or perform other equivalent functions. Given our tiny membership, meager budget, and lack of any office space, we possess neither the time nor the resources to routinely schedule campus rooms or advertise extensively for outside organizations, as is the norm for most recruiting events. Moreover, such copious involvement would dramatically constrict our ability to organize other, non-recruiting events. The above email address falls short of duplicating the excellent assistance provided by the HLS Office of Career Services. We sincerely hope, however, that it satisfies some needs of our interested classmates and that they feel entirely comfortable in approaching us as peers.â€

When the federal government responded by threatening to withhold all federal aid from Harvard, Kagan rescinded the prohibition.  Kagan wrote the following to the student body at the time: “I have said before how much I regret making this exception to our antidiscrimination policy. I believe the military’s discriminatory employment policy is deeply wrong – both unwise and unjust. And this wrong tears at the fabric of our own community by denying an opportunity to some of our students that other of our students have. The importance of the military to our society – and the great service that members of the military provide to all the rest of us – heightens, rather than excuses, this inequity. The Law School remains firmly committed to the principle of equal opportunity for all persons, without regard to sexual orientation. And I look forward to the time when all our students can pursue any career path they desire, including the path of devoting their professional lives to the defense of their country.â€

The government successfully petitioned for certiorari. In the Supreme Court, Kagan joined thirty-nine other law professors in signing an amicus brief in support of FAIR.

The Supreme Court subsequently upheld the Solomon Amendment, rejecting the position of FAIR and its amici (including Kagan), unanimously. After stating that the law school would of course follow the Court’s ruling, Kagan wrote: “At the same time, I hope that many members of the Harvard Law School community will accept the Court’s invitation to express their views clearly and forcefully regarding the military’s discriminatory employment policy.  As I have said before, I believe that policy is profoundly wrong — both unwise and unjust — and I look forward to the day when all our students, regardless of sexual orientation, will be able to serve and defend this country in the armed services.â€

Some commentators have claimed that Kagan’s position on the Solomon Amendment reflects an anti-military bias. That criticism is unsound. Harvard’s position – which predates Kagan’s tenure as dean – was not directed at the military but instead is a categorical nondiscrimination rule applicable to all potential employers. It is a position that is widely shared among American law schools.

It is fair to infer from the fact that Kagan did not attempt to repeal Harvard’s policy, and instead implemented it in full in the wake of the Third Circuit’s ruling despite the stay of the mandate, and moreover wrote to the student body in unambiguous terms, that Kagan personally supports the policy in full. But that is just to say that Kagan believes in the principle of nondiscrimination, including with respect to homosexuals.

There is no evidence that Kagan harbors any hostility towards the military. She hosted dinners at Harvard for veterans. Her email to the student body, quoted above, takes care to state her respect for the military, a topic about which she has spoken clearly. For example, when she was invited to give the distinguished Evening Lecture at West Point (available here), General Kagan explained that she was “in awe of [the cadets’] courage and dedication†and recognized that “my security and freedom and indeed everything else I value depend on all of you.â€Â Kagan explained that in light “of the vital role the military plays in the well-being of the country,†she was “grieved†at the conflict between the military and law schools, including her “personal[]†belief “that the exclusion of gays and lesbians from the military is both unjust and unwise.â€Â It was precisely because of her respect for the military that she “wish[ed] devoutly that these Americans could join this noblest of all professions and serve their country in this most important of ways.â€

Confirmation as Solicitor General [by Erin Miller]

Kagan’s confirmation hearing was not particularly contentious. Probing questions focused on two issues: Would she defend statutes to which she was personally opposed? And was she qualified for the position given her inexperience as an advocate?

To the first concern, Kagan repeatedly affirmed that personal qualms about a statute would never prevent her from enforcing it: “When one assumes the Solicitor General’s role, one is assuming a set of responsibilities–a set of obligations–of which the defense of statutes is one of the most critically important. And you defend those statutes whether you would have voted for those statutes or not.” She would have defended the Solomon Amendment, she explained, because “of course there was a reasonable basis” for it.

Senators Tom Coburn and Arlen Specter wondered whether Kagan would defend statutes against the president’s will. Kagan replied that she would almost certainly do so, given that presidential opposition would seldom undermine the legal basis for a statute. The one, narrow exception might be if the statute infringed on a “core” presidential function. Here she recited the framework of presidential power articulated in Youngstown Sheet & Tube v. Sawyer, which deems that power at its “lowest ebb” when Congress has spoken against it.

Answering the second concern about her lack of experience in legal practice, Kagan cited among her qualifications to be Solicitor General her “judgment as opposed just to book learning” and her “lifetime of learning and study of the law, and particularly of the constitutional and administrative law issues that form the core of the Court’s docket.”

During the hearing, Kagan distanced herself from some views expressed early in her career that will likely give rise to questions again if she is nominated to a seat on the Supreme Court. Kagan called a memorandum that she wrote as a law clerk to Justice Thurgood Marshall “the dumbest thing I ever read.” “Let me step back a little if I may and talk about my role in Justice Marshall’s chambers…We wrote memos on literally every single case in which there was a petition…I don’t want to say there is nothing of me in these memos, but I think in large measure these memos were written in the context of–you’re an assistant for a justice, you’re trying to facilitate his work, and to enable him to advance his goals and purposes as a justice…I was a 27-year-old pipsqueak and I was working for an 80-year-old giant in the law and a person who–let us be frank–had very strong jurisprudential and legal views…and he was asking us in the context of those cert. petitions to channel him, and to think about what cases he would want the Court to decide…”

Kagan also said “I’m not sure that, sitting here today, I would agree” with her prior position (stated in the book review quoted above) that Supreme Court nominees should answer questions about their substantive legal views and even possible votes.

Another noteworthy exchange involved executive power.  Senator Lindsay Graham asserted that, under military law, a member of an enemy force can be detained without trial. When he explained that Attorney General Holder had agreed with that statement in his hearing and asked Kagan whether she agreed, she replied “I think that makes sense, and I think you’re correct that that is the law†(see hearing video at 1:37:35).

In response to written questions, Kagan declined to answer a question from Senator Specter regarding the rights of detainees held at the Bagram Air Force Base on the ground that she might one day have to participate in ongoing litigation on that question.

Kagan also addressed the Solomon Amendment. “As the dean of a law school with a general nondiscrimination policy – meant to protect each of our students regardless of such factors as race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation – I thought the right thing to do was to defend that policy and to do so vigorously. For that reason, when the Third Circuit held the Solomon Amendment unconstitutional, I reinstated the school’s policy pending the Supreme Court’s decision in Rumsfeld v. FAIR. (Of course, Harvard Law School has been in full compliance with the Supreme Court’s decision since the day it was issued.) As Solicitor General, I would have a wholly different role and set of responsibilities.â€

Kagan elaborated as well on the memorandum to Justice Marshall discussed above. “I indeed believe that my 22-year-old analysis, written for Justice Marshall, was deeply mistaken. It seems now utterly wrong to me to say that religious organizations generally should be precluded from receiving funds for providing the kinds of services contemplated by the Adolescent Family Life Act. I instead agree with the Bowen Court’s statement that ‘[t]he facially neutral projects authorized by the AFLA-including pregnancy testing, adoption counseling and referral services, prenatal and postnatal care, educational services, residential care, child care, consumer education, etc. are not themselves “specifically religious activities,†and they are not converted into such activities by the fact that they are carried out by organizations with religious affiliations.’ As that Court recognized, the use of a grant in a particular way by a particular religious organization might constitute a violation of the Establishment Clause – for example, if the organization used the grant to fund what the Court called ‘specifically religious activity.’ But I think it incorrect (or, as I more colorfully said at the hearing, ‘the dumbest thing I ever heard’) essentially to presume that a religious organization will use a grant of this kind in an impermissible manner.â€

Materials from the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing:

Hearing video (which was consolidated with the hearing on the nomination of Tom Perrelli as Associate Attorney General)

Materials entered into the record (available all together here):

- Kagan’s responses to written questions: All responses | Index

- Letters received in connection with the nomination, including an endorsement by past Solicitors General

- Nominee questionnaire and attachments

Tenure as Solicitor General [by Tom Goldstein]

Elena Kagan is the nation’s first female Solicitor General. Her official profile is available here. (Barbara Underwood previously held the position on an “acting†basis.)

The Office of the Solicitor General represents the United States before the Supreme Court. The Solicitor General herself tends to argue the government’s most significant cases before the Court. She also must personally approve the government’s appeals, appellate rehearing requests, and amicus filings.

At the time of her confirmation, like Robert Bork and Kenneth Starr before her, Kagan had not previously argued at the Court. She elected not to argue a significant voting rights case (NAMUDNO) immediately upon taking office, deferring to the lawyers who had prepared the case.

Her first argument came instead in September 2009 in the well-known Citizens United campaign finance case. The government lost the case by a vote of five-to-four.

In addition to Citizens United, Kagan personally argued five other cases: Salazar v. Buono (wiki entry here; opinion here; transcript here), involving a cross on government land, in which the United States prevailed; Free Enterprise Fund v. PCAOB (wiki entry here; transcript here), involving the body that issues regulations implementing the Sarbanes-Oxley statute; United States v. Comstock (wiki entry here; transcript here), involving the constitutionality of a statute authorizing the civil confinement of sexually dangerous prisoners; Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project (wiki entry here; transcript here), involving the material support for terrorism statute; and Robertson v. United States ex rel. Watson (wiki entry here; transcript here), involving a private party’s right to pursue a charge of criminal contempt.

Some critics (and supporters) attribute to Kagan views on certain legal issues based on positions she took as Solicitor General. That criticism (and praise) is misguided. The Solicitor General acts as the attorney for the United States and therefore asserts the position of the government, without regard to whether she personally shares the same view. For Kagan not to have zealously pursued the interests of the United States in each case would have been an abdication of her duties. There are only a few exceptions – rare throughout our history – in which the Solicitor General concludes that the government’s position has no reasonable basis and therefore refuses to assert it; Kagan has not participated in such an extreme case.

Executive Power [by Tom Goldstein]

Some have criticized Elena Kagan for supposedly favoring a strong view of executive power. They equate her views with support for the Bush Administration’s policies related to the “war on terror.â€Â Generally speaking, these critics very significantly misunderstand what Kagan has written.

Kagan’s only significant discussion of the issue of executive power comes in her article Presidential Administration, published in 2001 in the Harvard Law Review. The article has nothing to do with the questions of executive power that are implicated by the Bush policies – for example, power in times of war and in foreign affairs. It is instead concerned with the President’s power in the administrative context – i.e., the President’s ability to control executive branch and independent agencies. That kind of power is concerned with, for example, who controls the vast collection of federal agencies as they respond to the Gulf oil spill and the economic crisis.

Nor does the article assert that the President has “power†over the other branches of government in the constitutional sense – i.e., a power that cannot be overridden. To the contrary, Kagan “accept[s] Congress’ broad power to insulate administrative activity from the President.â€Â (2251). She instead makes the descriptive claim “that Congress has left more power in Presidential hands than generally is recognized.â€Â (Id.)

Kagan does believe that presidential control over the agencies is a good thing. As a policy matter, but not as a constitutional matter, she therefore shares some common ground with conservatives who believe in a strong, unitary executive. Conservatives want that presidential control because they believe that it is the best interpretation of the Constitution and because it increases the prospect that agencies can be blocked from running amok, generally by engaging in excessive regulation.

But Kagan favors the idea of Congress allowing strong presidential control for a very different reason. Based on her then-recent experience in the Clinton Administration, she explains that a progressive President needs control over the agencies to press his agenda. “Where once presidential supervision had tended to favor politically conservative positions, it generally operated during the Clinton Presidency as a mechanism to achieve progressive goals. . . . Clinton showed that presidential supervision could jolt into action bureaucrats suffering from bureaucratic inertia in the face of unmet needs and challenges.â€Â (2249).

There is no link between Kagan’s views on the value of Congress permitting strong Executive control of administrative agencies for purposes of achieving progressive goals and the claim that the Bush Administration had the constitutionally conferred power to engage in policies like the NSA wiretapping program and indefinite detention in the war on terror. They have literally nothing to do with each other.

Critics equally misunderstand a 2006 article in the Yale Law Journal by Kagan’s deputy, Neal Katyal (who prevailed [with me as co-counsel] in the Hamdan case), when they assert that Katyal views Kagan as asserting a Bush-like vision of presidential power. Neal K. Katyal, Internal Separation of Powers, 115 Yale L. J. 2314 (2006). Katyal’s article does nothing of the sort. Katyal points to Kagan’s view that presidential control encourages “executive energy and dispatch.â€Â (2317). Katyal believes that a strong Executive “fails to control power†when one party controls the Congress as well. (2332). But he flatly recognizes that her article is addressed to “domestic policy,†and he merely analogizes to how similar arguments could be made “in the realm of foreign affairs†(2343), which as noted Kagan was not doing. Kagan’s article, Katyal explains, “is about [Clinton’s] attempt to use the President’s authority to achieve domestic policy goals,†and Kagan “excludes or distinguishes foreign policy. As such, the above analysis is not a direct criticism of her article but rather of attempts to extend her concept to foreign affairs.â€Â (Id.) I do think that the two articles suggest that Kagan and Katyal (both veterans of the Clinton Administration) differ to some extent on the question whether it is a good or bad thing for the President to exercise strong control and direction over agencies, but that disagreement again has nothing to do with the foreign-affairs-related issues raised by Kagan’s critics.

Liberal commentators also point to a brief exchange between Lindsay Graham and Kagan at her confirmation hearings. As discussed above, Senator Lindsay Graham asserted that, under military law, a member of an enemy force can be detained without trial. When he explained that Attorney General Holder had agreed with that statement in his hearing and asked Kagan whether she agreed, she replied “I think that makes sense, and I think you’re correct that that is the law†(see hearing video at 1:37:35).

It seems to me that liberals’ reliance on that passage is dramatically overblown. Kagan was asked whether the Attorney General, for whom she would work directly, was right in his understanding of existing law. The question had nothing to do with Kagan’s own views. And a single sentence in a confirmation hearing is far too slender a reed on which to base an understanding someone’s views on a question as complicated as the President’s power in war time.

The point is easily illustrated by a similar exchange with Dawn Johnsen, whom liberals celebrate as an ideal nominee, but who withdrew from consideration to head the Office of Legal Counsel after having been blocked. Johnsen notably had been exceptionally critical of the Bush Administration’s policies in the war on terror. In written questions subsequent to her confirmation hearing, Senator Hatch asked Johnsen whether she agreed with Kagan’s answer that Kagan agreed with Holder. She responded: “Yes, I do agree with Dean Kagan’s statement that under traditional military law, enemy combatants may be detained for the duration of the conflict. That is what the Supreme Court said as well in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004). . . . As indicated above, I do not believe that release or criminal prosecution are the only possible dispositions for detainees.â€Â No one believes that Johnsen was embracing the Bush Administration’s policies, and no one should think that was true of Kagan either.

Likely Senate Votes For Confirmation [by Tom Goldstein]

Elena Kagan’s relatively recent confirmation as Solicitor General provides an unusually good window into how she would fare in the Senate if nominated to succeed Justice Stevens.

Generally speaking, I find it unlikely that Kagan would get many (if any) more votes than the 68 received by Justice Sotomayor, whom some Republicans found it difficult to oppose because she was the third female Justice, the first Hispanic, and had a powerful personal story. The Senate is also now more rigidly divided along party lines, in the wake of the health care fight. Although there were several facts in Sotomayor’s record that demonstrated that she was relatively liberal – including not only her opinions but also her pre-judicial work for advocacy groups – whereas Kagan’s record is far thinner on ideological questions, I expect that Republicans’ votes on the Sotomayor nomination will substantially guide their approach to a Kagan nomination.

Many Republicans will have a significant predisposition to oppose almost anyone whom a Democratic President nominates. A material number of Democratic Senators took the same approach to President Bush’s nominees.

The most significant point that makes it possible that Kagan could come close to or surpass Sotomayor’s vote count is that Sotomayor did face significant opposition from a uniquely powerful interest group – the NRA – on the basis of a case on which she sat that ruled (applying prior Second Circuit precedent) that the Second Amendment is not incorporated against the states. The NRA will naturally be suspicious of any Democratic nominee, but Kagan does not appear to have the “hook†for them to engage in active opposition. I am not aware of any position she has taken – before or during her tenure as Solicitor General – on the Second Amendment.

Kagan was confirmed as Solicitor General by a vote of 61 to 31, with 7 Senators not voting. The 61 “yes†votes were 52 Democrats, the 2 Independent Senators who caucus with the Democrats (Joe Lieberman and Bernie Sanders), and 7 Republicans. 31 Republicans (including now-Democrat Arlen Specter) voted against her.

4 Democrats and 3 Republicans did not vote. The 4 Democrats were not centrists or conservatives abstaining as a signal of opposition; they were Boxer, Kennedy, Klobouchar, and Murray.

It is reasonable to expect that Kagan would get the votes of all the Democratic Senators, except possibly one. In the past five Supreme Court appointments – Ginsburg, Breyer, Roberts, Alito, and Sotomayor – a Senator of the President’s party voted against a nominee only a single time (out of 494 votes cast): Republican Senator Lincoln Chafee voted against Samuel Alito. Particularly given that Specter is the only current Democrat to have voted against Kagan for Solicitor General, and nothing dramatic has emerged during her tenure or from her record, it is fair to predict that he is the only possible Democratic vote against her for Associate Justice. She thus starts from a base of 56 votes: the 57 Democrats.

I don’t see any reason to believe that Independent Senators would vote against Kagan now. That makes 58.

Levels of support from the opposing party are far harder to predict. There was widespread support from Democrats for Justice Scalia and from Republicans for Ruth Bader Ginsburg. But the numbers for recent appointments have been much lower.

At the threshold, I don’t see any reason that the 30 Republicans who opposed Kagan for Solicitor General would change their minds. The stakes are higher. The vote for her confirmation as Solicitor General was also a relatively open prelude to a potential Supreme Court nomination.

So, with 58 votes for and 30 votes against, there are 14 remaining possible pick-ups. An average of 99 Senators have voted on recent Supreme Court appointments, so it is fair to assume that every or nearly every Senator will vote.

Two further votes for Kagan seem almost certain. The Senators from Maine – Snowe and Collins – voted for Kagan for Solicitor General and consistently have taken moderate positions on judgeships, including voting for Sonia Sotomayor. That makes 60 votes.

After that come four Senators whom I regard as essentially toss-ups and who may well vote together: Specter, Judd Gregg of New Hampshire, and Richard Lugar of Indiana, who voted for Kagan for Solicitor General and for Sotomayor, and is independent minded; and Lindsay Graham of South Carolina, who has played a leading role in trying to bridge the gap between the parties over judgeships and voted for Sotomayor. (Graham did not vote on Kagan’s Solicitor General nomination.) I think each will be concerned that Kagan’s views on judging will be opaque at her hearing, but all ultimately will vote for her. That makes 64 votes.

Three other Republicans voted for Kagan for Solicitor General and are accordingly worth watching: Hatch of Utah; Kyl of Arizona; and Coburn of Oklahoma. Each of those states is relatively conservative, having voted for John McCain. Of these three, I think that only Hatch will vote to confirm Kagan; he has tended to show Presidents significant deference in this area. He did vote against Sotomayor, but that was because he was troubled by her record, which does not have a parallel with Kagan, about whom he has spoken favorably. That makes 65 votes.

A new member has also joined the Senate, Republican Scott Brown. I have relatively little guidance on how he will vote, but expect that in this important first vote he will stick with the party majority and vote “no.â€

So, in the end, I anticipate that Elena Kagan would receive approximately 65 votes in favor of her confirmation (3 fewer than Sotomayor): all 57 Democrats; 2 Independents; and 6 Republicans (Snowe and Collins; 2 Republicans on the Senate Judiciary Committee – Graham and Hatch; and Gregg and Lugar).

On this count, 6 Republicans would vote for Kagan. 10 Republicans voted for Sonia Sotomayor. 4 Democrats voted for Samuel Alito. 22 Democrats voted for John Roberts. The most apt comparison among the nominees with respect to what is known about their ideological views is Kagan and Roberts; the gap between the 22 Democratic votes he received and the 6 Republican votes she will receive on my count would be significant.

Although the vote will not be overwhelming, there is no reason to believe that the process will be particularly contentious or that her confirmation would ever be in doubt. Nor would there be a threat of a filibuster.

It is worth pausing on the reasons that Republicans will invoke in voting against Kagan, who has a thin track record on ideological questions that would provide a substantial basis for opposition. In the case of Sonia Sotomayor, Republicans’ stated opposition focused on three things: her vote in the Ricci (white firefighters) case; her vote in the gun-rights case discussed above; and her repeated “wise Latina†references in speeches.

For Kagan, I expect the stated rationales for “no†votes will be her position on the Solomon Amendment (discussed above) and (what I presume will be) her determination not to provide significant detailed answers to Senators’ substantive questions about legal issues, in contrast with the views set forth in her law review article on Supreme Court confirmations. I anticipate that Republican Senators will refer to what they call a “Kagan standard†derived from the article that she does not satisfy. The fact that other recent nominees (including the nominees of President Bush) have been no more forthcoming but received Republican votes will go unmentioned. The Administration also presumably will withhold certain memoranda from her time at the White House as privileged, leading to further Republican objections.

Recusal [by Tom Goldstein]

I’ve previously discussed the effect of Elena Kagan’s role as Solicitor General on the extent to which she would be required (or would elect) to recuse herself from cases before the Court. This final Section is an only slightly revised discussion of that point. I do update certain numbers based on a updated assumption that Kagan would be nominated – and would begin recusing herself as Solicitor General – on May 10 rather than May 1, and also to incorporate the points that I originally made as an addendum in responding to Ed Whelan.

Assertions that Kagan would recuse herself from a significant number of cases have been extrapolated from the experience of the most recent Solicitor-General-turned-Justice:Â Thurgood Marshall, who recused himself from a majority of merits cases in his first Term (1967) on the Court.

The numbers for Kagan would not be nearly as dramatic. For the reasons that I give below, I estimate that Kagan would recuse from 16 merits cases in her first Term. In Marshall’s second Term, he recused from 8 cases because of his role as Solicitor General; I estimate that the number for Kagan would be 6.

In no particular order, Kagan would have far fewer recusals principally because (i) she would recuse herself earlier in the year, (ii) the Court’s docket has fewer merits cases with the United States as a party now than it did in 1967, and (iii) a substantial number of Marshall’s recusals arose for reasons other than his service as Solicitor General that are not applicable to Kagan.

Marshall served as a Judge on the Second Circuit from 1961 to 1965. He was the Solicitor General from August 1965 to August 1967. He was nominated to the Supreme Court on June 13, 1967, and served as an Associate Justice beginning August 30, 1967. In the interim, Marshall appears to have continued to serve as Solicitor General (signing briefs and taking on more recusal obligations as a consequence); he did not recuse from serving as the Solicitor General on the basis of his pending Supreme Court nomination.

In his first Term, Marshall recused from 61 argued cases (as opposed to all decided cases), for varied reasons. (The only other Solicitor General who was directly appointed as a Justice, Stanley Reed, appears to have recused from 29 merits cases in his first Term on the Court (which he joined in January 1938).)

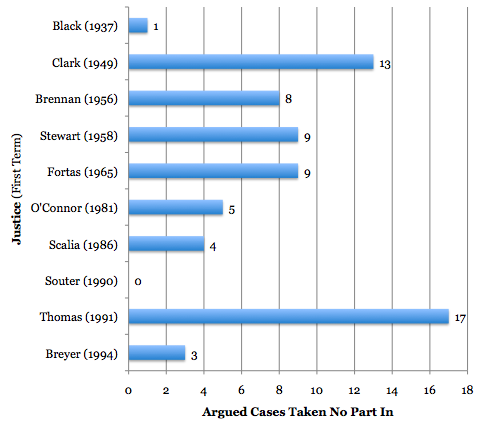

The level of nonparticipation by Marshall (and Reed) is far higher than by most Justices in their first Term. Erin Miller collected this illustrative data for ten examples:

Because the focus of commentary has been on Marshall’s recusals, I reviewed them all, both at the merits and (where applicable) cert. stages, and for many their prior history.

Most of the recusals – 53 – relate to Marshall’s service as Solicitor General. Marshall appears to have applied a rule that he would recuse from any case in which he had personally participated (or at least in which his name appeared on the brief). (There are several cases in his first Term in which the United States was a party or an amicus and Marshall’s name did not appear on the government’s papers, and in which he participated as a Justice.)

In most cases in which Marshall recused based on his role as Solicitor General (48), his personal participation in the case is obvious because his name appears on the government’s briefs at the cert./probable jurisdiction stage (33) or the cert./probable jurisdiction and merits stages (15). In 4 other cases, his recusal indicates that he played some other role – for example, authorizing an appeal. A final case was related to another ruling in which he was otherwise recused.

5 further recusals by Marshall in argued cases appear to relate to his service on the Second Circuit. 2 appear tied to his prior work with the NAACP. In 1 other case, I cannot figure out why he recused.

There is another, smaller body of 4 cases in which Marshall recused when the Supreme Court ruled on the merits without argument – i.e., it disposed of them summarily. In 2, his name is on the briefs; 1 is a continuation of prior litigation in a Supreme Court case from his time as Solicitor General; and in 1 it appears he authorized the appeal.

There is a final group of 11 cases in which Marshall recused that arguably would have been regarded as merits dispositions in 1967, but wouldn’t be now (and hence have no analog for Elena Kagan). In 7, the Court reversed the lower court’s judgment on the merits, merely by providing a citation to a prior Supreme Court ruling. Those cases would now be handled without deciding the merits by issuing an order vacating the ruling below and remanding to the court of appeals for further consideration. In the remaining 4, the Court summarily disposed of “appeals†– 3 times affirming and 1 time dismissing the appeal for “lack of a substantial federal question.â€Â This “appellate†docket has been essentially eliminated by a subsequent statute.

One quick point before moving on. Marshall’s large number of recusals don’t seem to have had a significant effect on the outcome of the decisions. The Court was equally divided 4-to-4 in only 2 of the cases.

I am not aware of cases in which Marshall recused himself because he had opined on the constitutionality of a federal statute as Solicitor General.  (Nor am I clear that such an opinion would trigger recusal.) Similarly, I am not aware (and I have tried to find out) of Elena Kagan playing such a role with respect to legislation that is likely to come before the Court. Analyzing legislation is not the job of the Solicitor General, as opposed to, for example, the Office of Legal Counsel. I do think that it is possible that in the next few Terms detainee-related cases in which she had played a role would come before the Supreme Court, which would trigger recusal. But whether and when that would occur is uncertain.

The upshot of the above is that on the basis of his service as Solicitor General, Justice Marshall recused from 57 merits cases in his first Term on the Supreme Court (53 argued and 4 summary reversals), which was roughly 40 percent of the Court’s merits docket that Term. That is a significant number, although materially less than the one commentators have been citing as the baseline from which to extrapolate how often Kagan would recuse.

Importantly, however, it does not follow that Elena Kagan would recuse from the same proportion of the docket as Marshall did. I do expect that she would apply the same ethical principle as Marshall: not voting in any case in which she personally participated as Solicitor General. But for three reasons, her number of recusals (both absolute and as a proportion of the Court’s docket) would be substantially lower than his.

First, I expect that Kagan would recuse much earlier in the Term (in late May) than did Marshall (in August). The consequence is that she would participate as Solicitor General in materially fewer cases that would come before the Court. I expect she would do so because the recent practice has been for nominees to cease participating in cases while preparing for confirmation hearings. Those nominees have been judges, but the principle is the same: the nominee is working on the confirmation process and is not in fact playing an active role in her nominal position. It would in fact be essentially fictitious for Kagan to sign her name to briefs as Solicitor General, when she would not in fact be working on those cases. Further, the prospect of recusals interfering with the Court’s business is a serious matter – because another judge cannot be appointed to take the place of a non-participating Justice – so that it makes sense to take reasonable steps to limit unnecessary recusals.

Second, the United States is a party somewhat less often now than it was in 1967. In the 1967 Term, the United States was a party in approximately 50 cases that were argued and decided on the merits, which was a little over 40 percent of the argument docket. In recent Terms, the average numbers have been 28 cases and a little below 40 percent.

Although the United States participates in far more cases as an amicus curiae on the merits now than it did then, those cases would trigger far fewer recusals for Kagan. Before the United States participates as a party on the merits, it must of course file papers at the cert. stage (signed by the Solicitor General), which is an early event that can trigger a recusal obligation. By contrast, when the United States comes in at the merits stage as an amicus – the current trend in the docket – the Solicitor General gets involved very late. Thus, if the Court is composed of 50 merits cases in which the United States is a party and 50 in which it is an amicus, a former Solicitor General will recuse from the party cases vastly more often, because s/he will have previously filed a brief in the party cases at the cert. stage.

Third, the Court’s merits docket in the 1967 Term was disproportionately stacked in the early months with merits cases in which the United States was a party early in the Term, and thus with cases triggering recusal by Justice Marshall. The 2011 Term does not have the same “shape.â€

In fact, it isn’t necessary to hypothesize about how often Kagan would be recused. We can identify the cases specifically.

Start with the existing merits docket for next Term, which produces 6 recusals. In 4 cases granted so far, Kagan would need to recuse: her name is on the briefs and the United States is a party: Abbott; Nelson; Flores-Villar; and Tohono O’odham. There are an additional 2 merits cases in which the United States participated as an amicus at the cert stage: Staub and Costco.

I expect that the rest of the current merits docket will produce 2 recusals, bringing the total to 8. There is a further group of 5 to 7 cases in which cert has been granted and in which I think the United States is likely to file an amicus brief at some point in the spring, though in most of them it will not do so soon. The practice of that Office is that the Solicitor General herself ordinarily participates only less than a week before the filing of an amicus brief, which would make the relevant due date May 21 (for a nomination of May 14, at which point she would be reviewing briefs to be filed a week later).  Based on the current briefing schedule, I expect that the government will file amicus briefs in 2 cases in that period.

I am not aware of any additional cases in which the Court has called for the views of the Solicitor General in which the Court is likely to grant cert., and in which Kagan would have participated in the government’s brief before May 14. I will say, however, that there is coincidentally a material difference between a nomination date of May 10 and May 21 (or even May 16). The government likely will file invited amicus briefs in a number of cases in time for the “cut-off†date for this Term of roughly May 23. Some number of those cases will be granted, and those briefs accordingly would generate recusals if reviewed by the Solicitor General. (The Solicitor General ordinarily does not participate in meetings with parties about those cases, but it is possible she has done so in a small number, which would itself trigger recusal.)

There are 3 further cases in which the Solicitor General has filed a cert petition. It is fair to assume that each of those will be granted, and Kagan would necessarily be recused from each.

Assuming a nomination on May 10, the categories above generate a total of 11 recusals:Â 6 merits cases; 2 merits amicus briefs; and 3 pending cert. petitions by the Solicitor General.

Because those 11 cases can be identified with specificity, it’s worth pausing on their significance and on the question whether the recusal is likely to change the case’s outcome. None has particularly broad jurisprudential or practical significance.  Flores-Villar v. United States could generate ideological disagreement, because it involves alleged gender discrimination. There are multiple cases involving suits against states by prison inmates, which have ideological overtones. One case – the government’s suit against the tobacco industry, in which the Solicitor General’s cert. petition is pending – would have significant financial consequences. (As with Marshall, there is no reason to believe that more than a few of the cases would result in an equally divided court.) None of the cases compares in importance to the Hamdan case in which John Roberts recused himself, having previously participated as a judge on the court of appeals.

Beyond the specifically identifiable cases, there are two categories of cases I haven’t yet covered.

First, there are many cert. petitions to which the United States has responded but on which the Supreme Court has not acted. (The Solicitor General often does not review briefs in opposition to certiorari, but because her name appears on the brief, I assume Kagan would regard that as sufficient participation to trigger recusal.) There is a lead time of essentially four weeks between the date a brief in opposition is filed and the date on which the Court grants certiorari. So, again assuming a May 10 nomination, there would be a group of cert. petitions in which the government filed oppositions in the period roughly between April 1 (the oldest oppositions not yet acted on) and May 7 (the final date Kagan would sign a petition) that could be granted and that could trigger a recusal obligation.

The best I can do is to extrapolate from the Court’s merits docket and say that 40 days represents one-ninth of the docket, which equates to just over 1 anticipated cert. grant (with around 11 cases a Term granted with the United States as respondent). To be conservative, I’ll estimate 2.

Second, there are cases in which Kagan would be recused because of her personal role in authorizing lower court litigation. The Solicitor General must personally approve any appeal, rehearing request, or amicus brief by the government. That is a significant body of cases. But it is not a large number of cases that end up at the Supreme Court. Here, we can conservatively extrapolate from the experience of Justice Marshall. Marshall served as Solicitor General for almost twice as long as Kagan would. In his first Term, Marshall seems to have recused in roughly 6 cases involving the federal government because of his approval role (or participation at some other point), without having signed a brief. On the low end, we could extrapolate 1 recusal for Kagan based on her approval role (because her overall recusal rate is such a small fraction of Marshall’s for the reasons discussed above) and because she would have served roughly half as long as Solicitor General. But I think a slightly higher number is appropriate because there is a large volume of federal government litigation and because the counter-point to her being nominated earlier in the Term than Marshall is that there will be more cases in which she played an approval role but did not sign the brief. So I estimate 3 recusals on this ground.

In sum, I would expect a total of 15 recusals – 6 pending merits cases, 2 merits amicus briefs, 2 pending cert petitions, 2 pending briefs in opposition, and 3 appeal recommendations – if Elena Kagan were nominated on May 10. That is roughly one-fifth to one-sixth of the merits docket, nowhere near the number or proportion of cases in which Marshall recused himself.

What about the following Term? As I mentioned, commentators have assumed that Kagan’s recusal obligations would continue to be very substantial for two to three years. That is not correct.

Absent an unusual circumstance, the greatest body of cases triggering recusal – those in which Kagan actually participated in the Supreme Court as the Solicitor General – would all be finalized during the upcoming Term. After that, her recusal would be triggered by cases in which she had the approval role, discussed above, which arrive at the Supreme Court far less frequently. In Marshall’s second Term, he recused from 14 merits cases (less than one-fourth of the pace from his first Term). 6 of those involved circumstances that likely would not apply to Kagan: 3 original jurisdiction rulings in which the United States was a party (with no similar pending cases now that I know of); 1 summary affirmance (with no jurisdictional parallel now); 1 case litigated by the NAACP; and 1 for which I cannot figure out why Marshall recused.  The 8 remaining cases seem to have involved Marshall’s approval responsibilities or litigation that returned to the Court from earlier Terms (which could happen with Kagan as well). Those 8 recusals by Marshall represent roughly 5 percent of the Court’s merits docket. If anything, the number for Kagan should be smaller because, as noted, she would have served a shorter time as Solicitor General. But to once again be conservative, I’ll estimate 5 cases.

In sum, I estimate that if Elena Kagan is nominated on May 10, 2010, she will recuse from 15 merits cases in October Term 2010 and 5 merits cases in October Term 2011. If correct, that level of nonparticipation would not be dramatically higher than the average in Erin’s illustrative sample above, and would be roughly equal to (or lower than) Justices Thomas and Clark. It would therefore not seem to be a significant basis for not appointing Kagan.

CORRECTION, May 11: This article originally listed the number of “scholarly articles” written by Kagan as five rather than six.