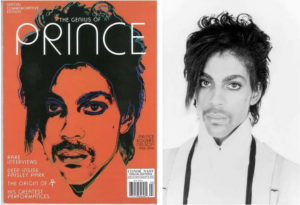

Justices debate whether Warhol image is “fair use” of photograph of Prince

Wednesday’s argument in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith wandered widely, as the justices considered whether a famous set of images that Andy Warhol based on a 1981 photograph of Prince by the award-winning photographer Lynn Goldsmith were such a “fair” use of the photograph that Warhol’s successors can license them for commercial use without the permission of (or compensation to) Goldsmith.

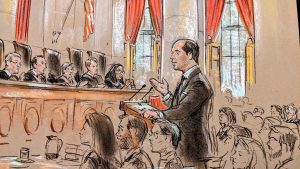

As Roman Martinez explained on behalf of the Andy Warhol Foundation (which controls the intellectual property of the late Warhol), the foundation argues that Warhol’s work was so transformative that the continuing exploitation of Warhol’s series of images after the death of Prince owed nothing to the photograph on which Warhol based those images. The principal reaction of the justices to the argument of Martinez was to pose a series of hypotheticals, all of which seemed to the questioner plainly to require permission from the underlying copyright, but none of which seemed obviously distinguishable from the foundation’s position that any new “message” or “meaning” is enough to free a follow-on work from any obligation to the original work.

Justice Elena Kagan put it most bluntly when she explained that under Martinez’s argument

there may be nothing left to the original author for derivative works. … [I]ndeed, we expect Hollywood, when it takes a book and makes a movie, to pay the author of the book. But I think moviemakers might be surprised by the notion that what they do [isn’t] transformative. I mean, mostly movies are tons of new dialogue, sometimes new plot points, new settings, new characters, new themes. You would think [that amounts to] new meaning and message [under the test you propose]. So why is it that we, you know, can’t imagine that Hollywood could just take a book and make a movie out of it without paying?

In the same vein, Justice Amy Coney Barrett (perhaps channeling my case preview) debated with Martinez why under his rule the acclaimed Peter Jackson movies about the Lord of the Rings needed to pay a royalty to Tolkien’s estate. Martinez started by suggesting that the movies had not added much of substance to Tolkien’s works but quickly backed down, confessing a general lack of familiarity.

More humorously, Chief Justice John Roberts posited a claimant who put a “little … smile” on Prince’s face – to press the message that “Prince can be happy.” Surely, he suggested, “[t]he message is different” from the (dour) face of Prince in the original photograph.

Most memorably, Justice Clarence Thomas asked Martinez to imagine him – let’s all practice our best imagining skills here – at a Syracuse football game, with a large poster bearing a blown-up image of “Orange Prince” (the image at issue in the case before the court) with a “Go Orange” caption at the bottom. After the game, Thomas suggested, he would be marketing the image “to all my Syracuse buddies.” The problem for Martinez, of course, is that the addition of “Go Orange” plainly adds a new “message” to Prince’s work, but the natural intuition is that a license fee still would be owed, a fee that is not easy to reconcile with Martinez’s argument.

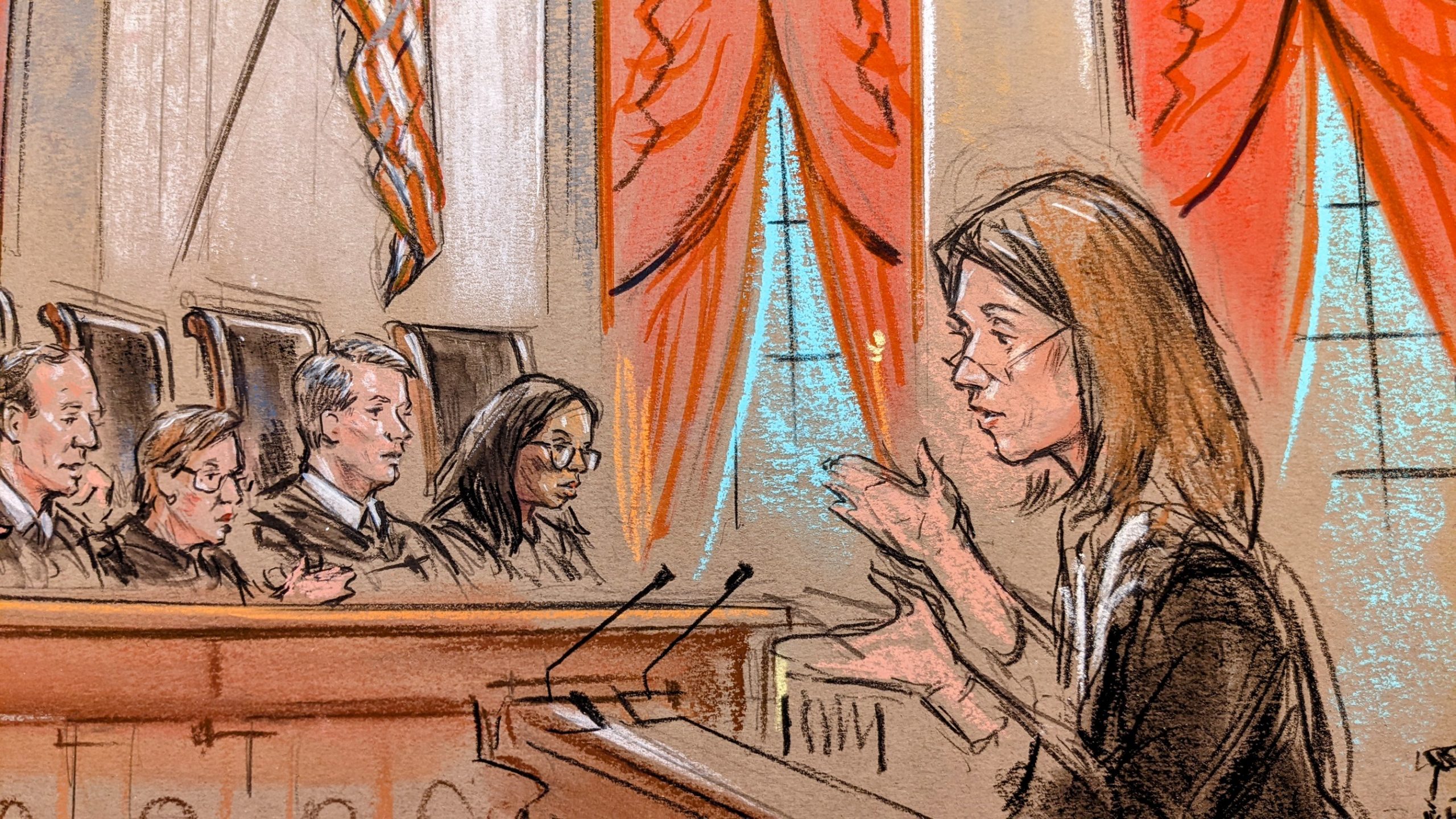

On the other side, the presentation of Lisa Blatt (representing Goldsmith the photographer) was largely occupied with more abstract discussions of what the statute (Section 107 of the Copyright Act) means when it directs attention to the “purpose” and “character” of the use. On the one hand, it is easy to say (as Blatt argues) that the “purpose” of both uses – Goldsmith’s photograph and the images Warhol derived from that photograph – was commercial licensing for publication in magazines in stories about Prince. On the other hand, you could just as easily say that Goldsmith’s original photograph was intended to provide an accurate representation of how Prince looked, while Warhol’s images had a profoundly non-representative intention.

Roberts seemed particularly interested in that point. He repeatedly returned to non-representative attributes of “Warhol’s depiction,” emphasizing that “if you really wanted to know what Prince looks like, … [h]e doesn’t have one eye that’s blacker than the other [and] his head doesn’t float in the air as it does in Warhol’s but not in Goldsmith’s.” As he put it, “Warhol sends a message about the depersonalization of modern culture and celebrity status.” Thus, he suggests, “it’s not just a different style. It’s a different purpose. One is the commentary on modern society. The other is to show what Prince looks like.”

Having said that, it is fair to say that much of the justices’ discussion with Blatt (and Yaira Dubin, representing the government in support of Goldsmith) seemed less concerned about figuring out which way to vote and more with how to craft a useful opinion rejecting Warhol’s claims.

In summary, the justices were highly engaged in this one, so I would not expect an opinion any time this fall. I think the principal question left for the justices will be whether they can affirm outright or whether they need to vacate the decision of the lower court and remand asking that it clean up some stray language in its existing opinion.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith