Justice Souter’s book list

David Souter was my first boss, during the 1987-88 term of the Supreme Court of New Hampshire, where I was privileged to serve as one of his two law clerks shortly before he was elevated to the United States Supreme Court. It became clear early on that “David,” which he insisted my co-clerk and I call him after the clerkship, was special, if not unique, both as a jurist and as a person. Putting aside his indisputable brilliance and astonishing breadth of legal and historical knowledge, he was kind, humble, incredibly hard-working, and utterly decent.

Far from the bookish recluse initially – and inaccurately – depicted by some in the media, those of us who had the privilege to know him know that he was also elegant, warm, and a gifted raconteur. He loved his friends and treated everyone with dignity and respect, from those who sat on the court to those who cleaned it. But he did love and was a voracious reader of books. Indeed, after he retired Justice Souter had to move from his ramshackle farmhouse to a sturdier one because he had been warned the old house could no longer structurally support the many thousands of books that had been stored there.

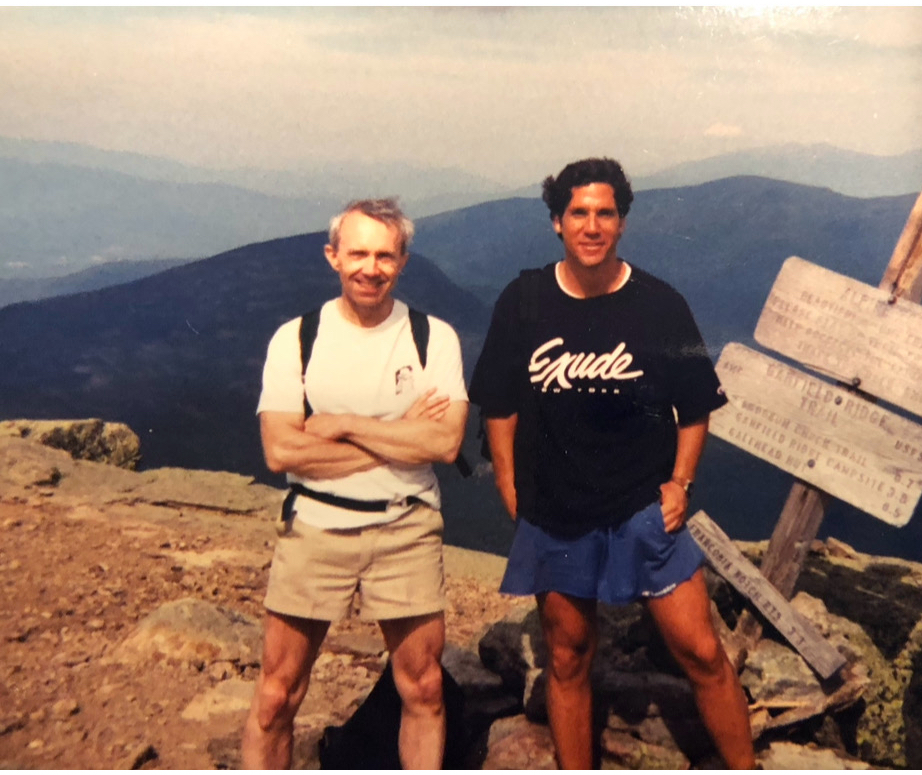

At the end of the term, when Justice Souter, my co-clerk, and I agreed the typical clerk-judge “farewell” lunch would not suffice, the three of us instead climbed Mount Washington, the tallest peak in his beloved White Mountains. The next night we drove to Boston in a chauffeured limousine my co-clerk and I rented for the occasion and had drinks at the Ritz. Those were followed by a walk across the Public Garden and the Common, with a stop along Beacon Street where we admired and were regaled by Justice Souter’s poignant stories about Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ sculpture of Civil War hero Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Regiment, one of the first Black regiments to serve in the Civil War. We then had a lavish dinner at his favorite restaurant, the venerable Locke-Ober Café. Although an austere Yankee (something we would often tease him about), Justice Souter was also quite generous. He always insisted on treating us.

This began a tradition of New England reunions that occurred virtually every summer from 1988 through the pandemic, during which we would hike up a mountain in the Presidential Range and then have drinks and dinner in Boston the next evening (sans limousine). My co-clerk and I relished these summer reunions, and Justice Souter told us he relished them, as well. At least he made us feel that way. He worked seven days a week during the Supreme Court term and this was an opportunity for him to unwind. No one who really knew him was at all surprised that in 2009, after serving nearly two decades on the court, he decided to trade “white marble for White Mountains,” as Chief Justice John Roberts put it. Unusual as it is, walking away from power was always his plan (and it was so true to who he was).

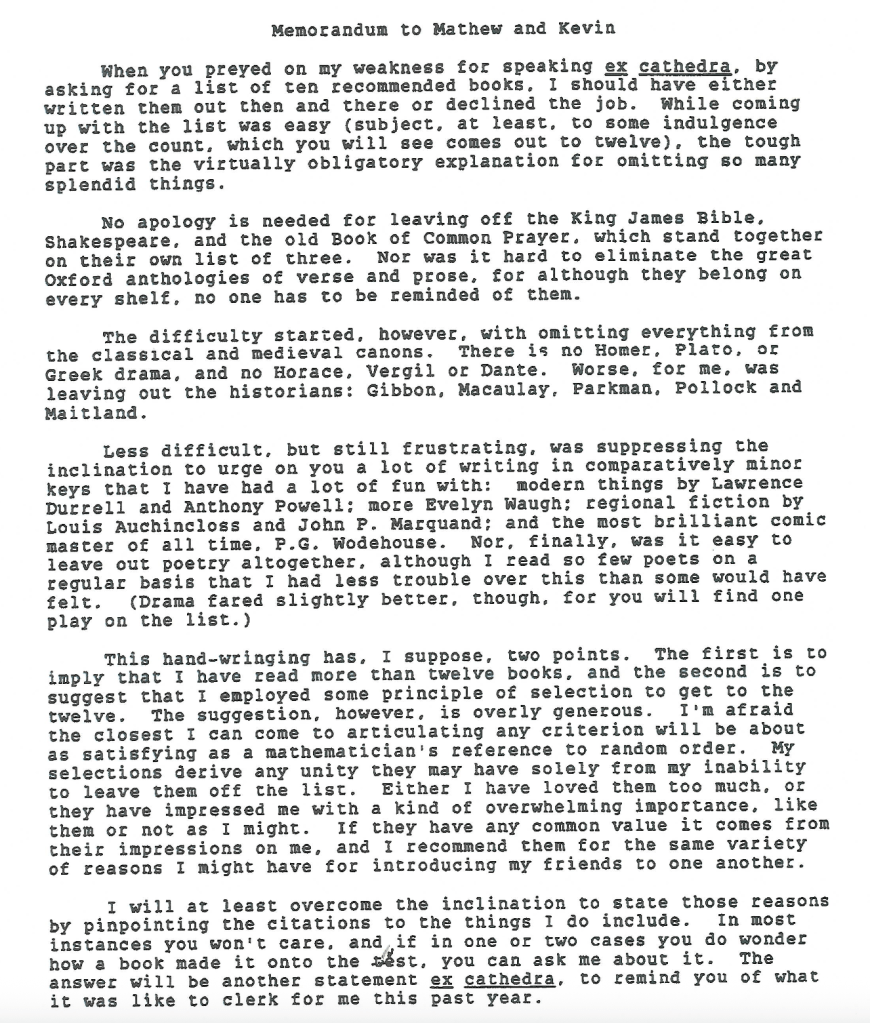

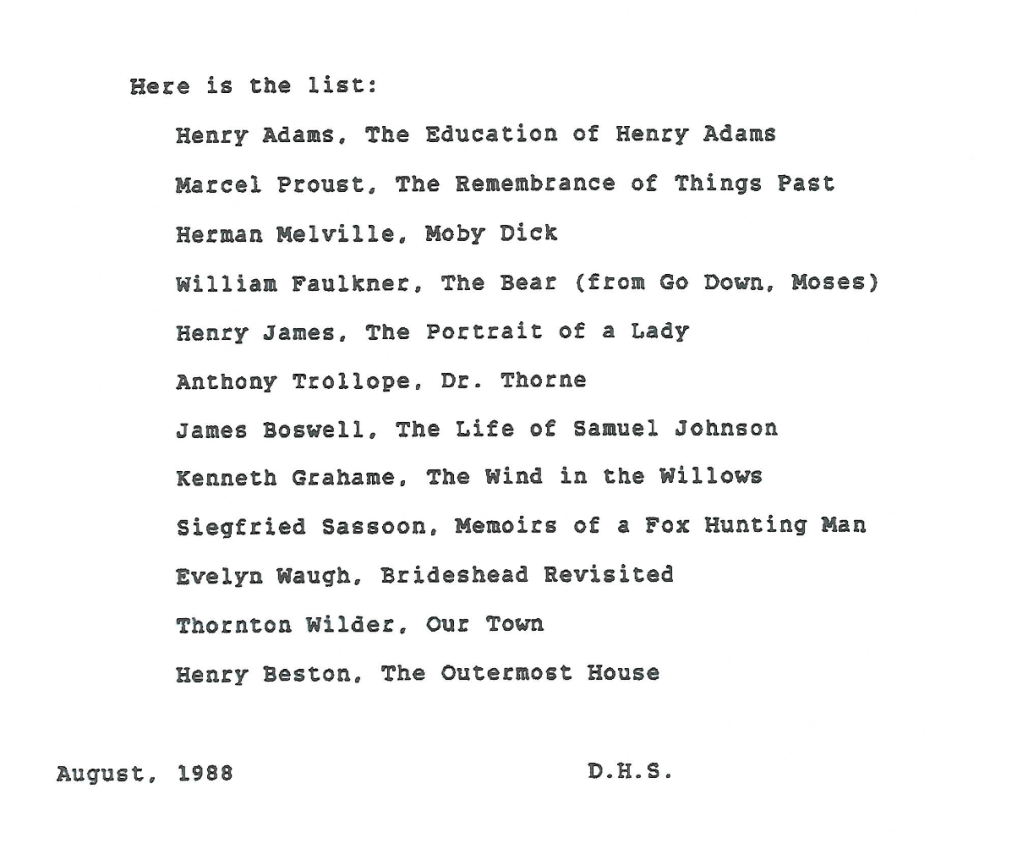

During these hikes we would reminisce, trade stories (his were far better and more interesting than ours), and always laugh. He might quote Robert Frost, explaining how The Road Not Taken was generally misinterpreted, or explain how Judge Learned Hand’s Spirit of Liberty speech informed his judicial philosophy. One annual topic concerned the justice’s “Top 10 Book List.” My co-clerk Kevin and I audaciously requested one early in the clerkship, but by the end of the term I thought he’d forgotten about it. So I was pleasantly surprised when I received an envelope the following summer that contained not only his list, but a full-page typewritten cover “Memorandum to Mathew and Kevin” regarding the difficulty of coming up with a mere 10 books. (In fact, the list itself came to 12.) After all, he noted, how could one omit “the classical and medieval canons”? And what about Shakespeare, “the great Oxford anthologies of verse and prose,” and, of course, “the Old Book of Common Prayer,” “Homer, Plato, or Greek drama”? Those alone would quickly exceed 10.

He would quiz me each year, genially, about my progress making it through his list, and each year I would have to confess failure in completing it, especially Proust, which I told him I just could not find the time for and which, regardless, I explained was beyond my capacity to appreciate fully. True to form, and as was the case with everything Souter, he would encourage me, just as he would when I would have to confess ignorance regarding the numerous literary or other allusions or quotations (often ancient ones) he might fluently, and unpretentiously, introduce into a conversation, assuming I would understand the reference. I’ve since learned I was in good company, as many former Supreme Court clerks, including U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit Judge Kevin Newsom and Harvard Law Professor Jeannie Suk Gersen, recently revealed having similar experiences with the justice. (Unlike Newsom, I did not even know who the great 17th Century English poet John Dryden was, but apparently none of us knew “what Dryden said.”) I could still hear Justice Souter say, in that distinct New England baritone, “Oh Mathew, you must read it, you will love it … but do it in a ‘gulp.’”

Even though Justice Souter had made clear to me that he “wouldn’t mind [the list] getting out” at some point, the time to release it never felt quite right. But the time now feels right for several reasons. Initially, the eloquence of the list itself serves as a tribute to a great justice and a great man, whose erudition, charm, and love of literature shines through – uniquely, I think. And relatedly, because although his puritan sense of propriety caused him to be reticent in speaking publicly as a justice or even a former justice (this was a man who would pay for his own postage stamps at work, lest the taxpayers be foisted with the cost), in the few speeches he did present, he passionately lamented that basic civics (implicit in his list) was no longer taught in school – and he feared that civic ignorance was perhaps democracy’s greatest peril. During several of his speeches, including a 2013 talk at the New York State Museum and a 2014 talk at Carnegie Mellon University (“The Heart of the Matter: The Humanities and Social Sciences for a Vibrant, Competitive, and Secure Nation”) that addressed a 2013 Report by The American Academy of Arts and Sciences, he also stressed the importance of reading, art, and the humanities, arguing they were essential for a civilized, healthy society and a strong democracy.

I believe the list is in service of these beliefs. Indeed, particularly in these partisan, polemical times, I cannot think of a better time to release the list so generously produced by my first boss, a man I miss dearly, who served the country with grace, humility, and honor.

Posted in Court Analysis