OPINION ANALYSIS

Leaving “rare birds” alone

on May 19, 2023 at 2:05 pm

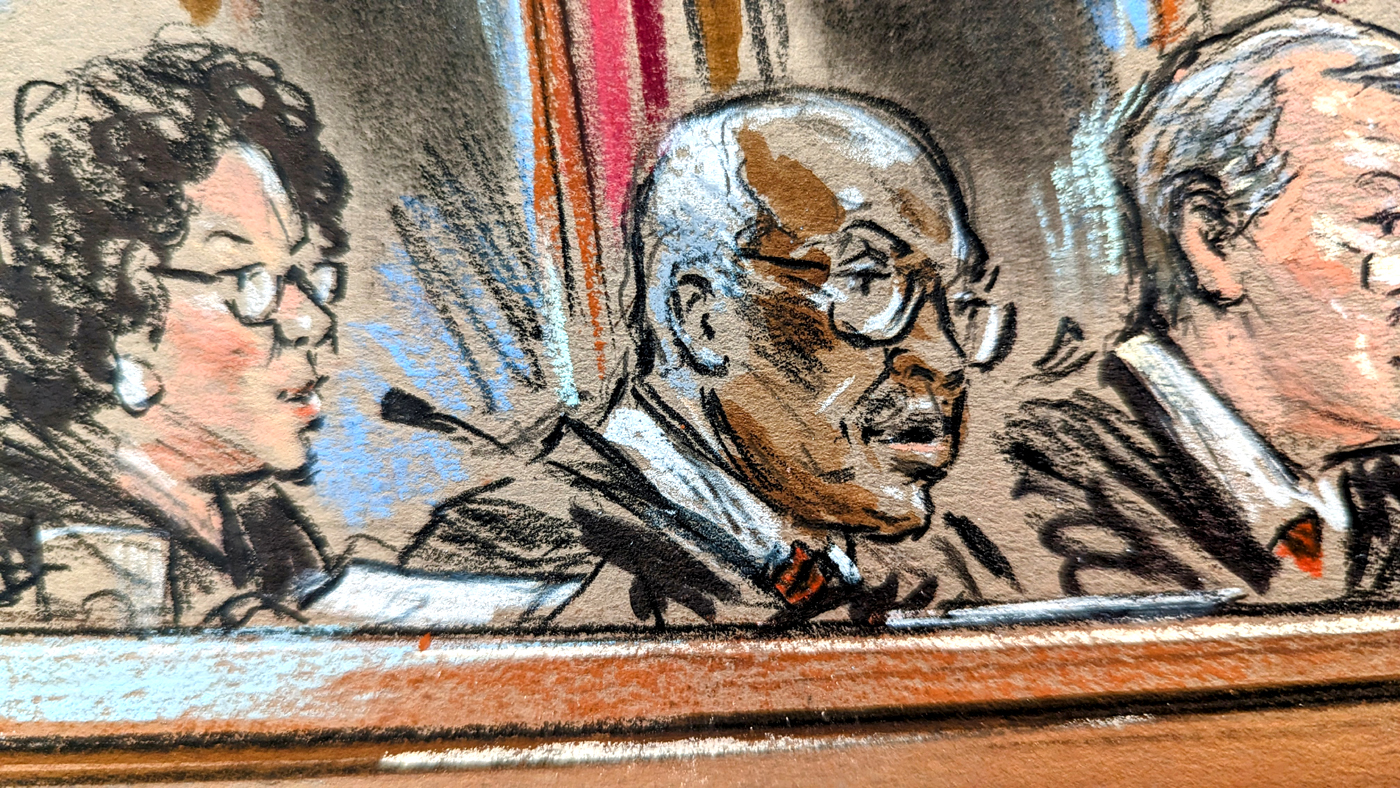

The Supreme Court has held that the Ohio National Guard’s dual-status technician employees have federal labor rights. In a 7-2 decision by Justice Clarence Thomas, the court said that the Ohio Adjutant General’s Department and the Ohio National Guard act as a federal “agency” when they hire and supervise dual-status technicians serving in their civilian roles. The federal agency that enforces collective-bargaining rights for federal employees, the Federal Labor Relations Authority, can therefore protect these workers and compel the Guard to bargain with unions.

The question before the court was whether the Federal Service Labor-Management Relations Statute applies to dual-status technicians working for the Guard. These “rare birds” occupy both civilian and military roles, serving as “civilian employee[s]” engaged in “organizing, administering, instructing,” “training,” or “maintenance and repair of supplies” to assist the National Guard while still being required “as a condition of … employment … [to] maintain membership in the [National Guard] and wear a uniform while working.” Except when participating as National Guard members in part-time drills, training, or active-duty deployment, dual-status technicians work full time in a civilian capacity and receive federal civil-service pay. Under the Technicians Act of 1968, each dual-status technician is considered “an employee of the Department of the Army or the Department of the Air Force, as the case may be, and an employee of the United States.”

If the technicians were solely employees of federal agencies, there would be no question that they enjoy collective bargaining rights. The FSLMRS establishes a comprehensive framework governing those rights in federal agencies. It secures the right of “[e]ach employee” “to form, join, or assist any labor organization, or to refrain from any such activity, freely and without fear of penalty or reprisal.” This statute also ensures that “each employee shall be protected in the exercise of such right.” Yet, the technicians have a “dual status” in the sense that they are employed and administered directly by the state Guard but, additionally, have federal status. This dual character formed the basis for the Guard’s challenge to the employees’ status as “federal” employees. Also, when directed by state (Guard) officials, the working conditions of the technicians were arguably not controlled by a “federal” agency. But the Guard could only “employ and administer” dual-status technicians working in their civilian capacity pursuant to an express federal “designat[ion]” of authority by the Secretary of the Army or the Secretary of the Air Force. The FLRA’s jurisdiction over the underlying unfair labor practices dispute, moreover, turned on whether the state Guard is a federal “agency” for purposes of the FSLMRS when acting in its capacity as direct supervisor of the dual-status technicians.

Despite the ambiguities in employee and agency definitions, the Guard had not questioned its collective-bargaining obligations over the years. It had a collective-bargaining relationship with the union, the American Federation of Government Employees, Local 3970, AFL-CIO, dating back to 1971, when the Guard first recognized the union as the exclusive representative of its dual-status technicians. The Guard and the union had since negotiated a number of collective-bargaining agreements, the most recent of which was signed in 2011 and expired in 2014.

As that collective-bargaining agreement neared expiration, the Guard and the union entered into negotiations for a successor agreement. They agreed to a memorandum of understanding in which the Guard promised to comply with the expired agreement until a successor agreement was reached. Later that year, the Guard reneged on this preliminary agreement, abruptly claiming that it was not bound by the expired collective-bargaining agreement. More dramatically, the Guard claimed it did not consider itself bound by the FSLMRS at all. The Guard also sent letters to dual-status technician union members, newly instructing them to submit forms permitting the deduction of union dues from their pay. The letters warned that if technicians did not promptly submit the forms, the Guard would cancel dues deductions on their behalf. The Guard ultimately terminated dues withholding for 89 technicians.

Throughout the litigation, the Guard argued that its actions were justified because it was not an “agency,” and dual-status technicians were not “employees” under the FSLMRS. The Federal Labor Relations Authority and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit rejected these arguments. The 6th Circuit held that the Guard is an agency subject to the FSLMRS when it operates in its capacity as an employer of dual-status technicians. The court of appeals further found that dual-status technicians are federal civilian employees with collective-bargaining rights under the statute.

On Thursday, the Supreme Court held that the Guard acts as a federal “agency” when hiring and supervising dual-status technicians serving in their civilian role. But it reached this conclusion solely on statutory grounds. The Guard abandoned an earlier constitutional argument that Congress lacked authority to define a federal agency to include state actors, so the case centered on whether the FSLMRS supported such coverage. The Supreme Court found that it did because the FSLMRS defines “agency” to include the Department of Defense, and each dual-status technician is (under other statutory authority) an employee of either the Department of the Army or the Department of the Air Force. Under various federal rules, “components” of fully covered agencies also fall within the FSLMRS’s reach. So, when the Guard employs and supervises dual-status technicians, it — like other components of a federal agency — exercises the authority of the Department of Defense, a clearly covered “agency.” Dual-status technicians are accordingly employees of the Secretaries of the Army and the Air Force, and the Guard is the Secretaries’ designee for purposes of dual-status technician employment. Moreover, because the Guard acts on behalf of federal agencies , with respect to its supervision of civilian technicians, its actions in that capacity do not implicate the balance between federal and state powers. Finally, although the creation of dual-status technicians predates enactment of the FSLMRS, “labor-management relations in the federal sector were governed by a program established” by a series of executive orders, “under which federal employees had limited rights to engage in” collective bargaining. Dual-status technicians were included in this program but could not have been had Congress or administrators entertained doubt about their status as federal employees.

In dissent, Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch argued that the majority failed to establish that the Guard was an “agency” within the meaning of the FSLMRS. Instead, they contended, the court proved only that dual-status technicians are federal employees, that the Guard “exercise[s] the authority of” a covered agency, and that pre-FSLMRS administrative practice supports the FLRA’s exercise of jurisdiction. “None of these grounds justifies the conclusion that any of the petitioners is an ‘agency’ subject to the FLRA’s remedial authority,” they wrote.