ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

Justices mull purpose of Hague Convention in international dispute over child custody

on Mar 28, 2022 at 10:25 am

On Tuesday the justices considered what obligations, if any, U.S. courts have to consider measures that might reduce the risk of harm if a child who has been abducted is returned to the country where she lives. The oral argument in Golan v. Saada was the latest case asking the justices to interpret the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, an international agreement adopted in 1980 to deal with international child abductions during domestic disputes. During just over 80 minutes of deliberation, the justices searched for a solution that would provide standards for lower courts but also lead to the speedy resolution of cases – a difficult task indeed, particularly in cases involving domestic violence.

Under the Hague Convention, children who are wrongfully abducted from the country where they live must be returned to that country, so that custody disputes can be resolved there. The rationale behind this mandate is that a parent should not be able to gain advantage in a custody dispute by abducting the child and taking her to a different country. The convention carves out an exception to that general return requirement, however, for cases in which there is a “grave risk” that returning the child would expose her to physical or psychological harm.

A federal court in New York ruled that the son of an American mother, Narkis Golan, and an Italian father, Isacco Saada, would face such a risk if he were returned to Italy, where he was born in 2016 and lived until his mother returned with him in 2018 to the United States, because Saada had been abusive toward Golan throughout the couple’s marriage. But under the law of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit, the trial court was also required to consider measures that would reduce that risk, and in this case the trial court ordered the return of the child, known as B.A.S., to Italy with a variety of measures in place to protect him. Golan came to the Supreme Court last year, asking the justices to review her case.

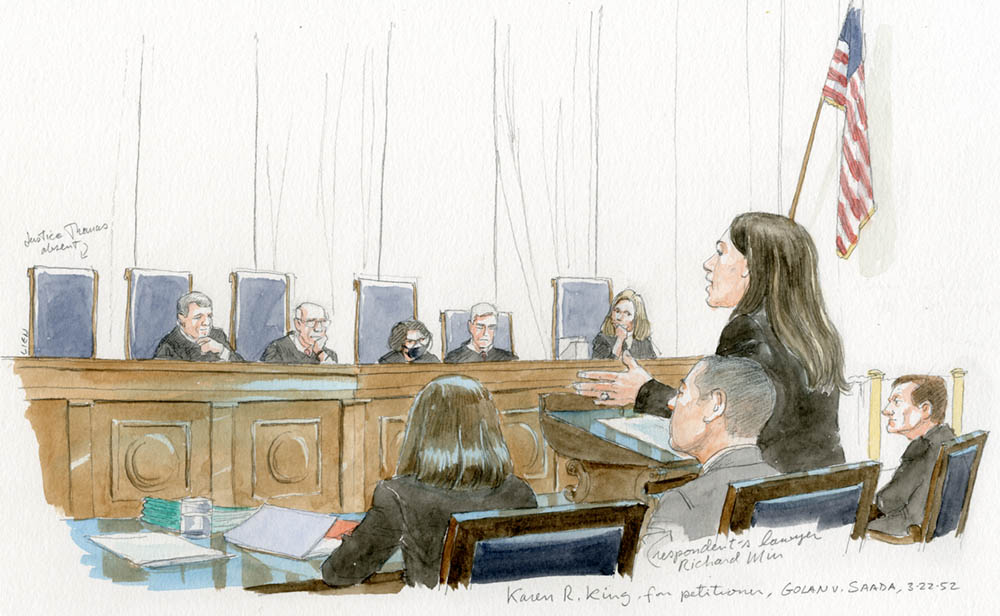

Representing Golan, lawyer Karen King argued that the 2nd Circuit’s rule requiring courts to “examine the full range of potential ameliorative measures and return the child if at all possible” was incorrect because, among other things, it has no basis in the convention’s text and is contrary to the convention’s goal of returning abducted children expeditiously. If the Supreme Court agrees, King told the justices, it should reverse the 2nd Circuit’s ruling and give B.A.S. – who, she noted, “is almost six years old” and “has spent the vast majority of his life in legal limbo” – “the safe and swift closure he deserves.”

Justice Elena Kagan suggested that King’s rule might be using the wrong analysis altogether. King, Kagan noted, had framed the task of the court as a two-step inquiry, looking first at whether there is a grave risk to the child if he is returned and then, if so, at whether there are measures that can reduce that risk. But wouldn’t the better approach, Kagan asked, be to consider risk-reduction measures as part of the original inquiry into whether there is a grave risk?

King conceded that there is “some overlap in the inquiry,” but she insisted that, at bottom, the two analyses should be separate. “If you combine the two,” she asserted, “you run the risk of making this trial extremely lengthy and wading into issues that a Hague expedited proceeding should not be wading into.”

Chief Justice John Roberts saw the issue differently. Two separate analyses, he contended, would take longer. Roberts repeated his concerns about delay later in the argument, when Frederick Liu, the assistant to the U.S. solicitor general who argued on behalf of the federal government, urged the justices to send the case back to the trial court, which would then reconsider whether B.A.S. faces a grave risk without the 2nd Circuit’s presumption that it would have to consider all possible measures to facilitate his return.

Justice Neil Gorsuch echoed Roberts’ concern. The trial court found a grave risk of harm after a nine-day trial, he noted. If the justices agree that the 2nd Circuit’s rule is too rigid, Gorsuch said to Liu, why wouldn’t the best course of action be to simply reverse the court of appeals and rule that the child should be allowed to remain in the United States, which would “at least allow the parties in this case to move on with their lives?”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor observed that beyond the goal of expedited proceedings, the convention’s primary goal “is an intent to return a child to its habitual residence.” Courts “can’t just eliminate” that goal when they find a grave risk of return, Sotomayor stressed.

Justice Samuel Alito objected to the idea that trial judges would have discretion to decide whether to return a child to a country where she would face a grave risk of harm. But if that’s the case, Alito continued, courts need standards to guide them in making their decision, even if the bright-line rule established by the 2nd Circuit has “gone too far.”

Justice Stephen Breyer voiced similar concerns. He told King that, despite the convention’s preference for the child’s return, “there will be a tendency to keep the child here” when the judge finds that she will face a risk of harm at home. “And I think what the 2nd Circuit wants to say” with its bright-line rule, Breyer suggested, “is remember the overall purpose of” the convention. If so, Breyer asked King, what rule could the Supreme Court adopt that would serve the same purpose without the “overkill” of the 2nd Circuit’s rule?

Justice Brett Kavanaugh asked Liu whether risk-reduction measures should be a possibility in cases, like this one, involving domestic violence. Although Golan contends that such measures “will almost never be appropriate in the context of domestic violence,” Liu declined to endorse a bright-line rule, noting that “even domestic violence cases vary in terms of their facts and circumstances.”

Arguing on behalf of Saada, lawyer Richard Min told the justices that the 2nd Circuit’s categorical rule best promotes the purpose of the convention and “ensures consistent results here in the United States and expectations for U.S. children abducted abroad by providing courts clear guidance on how to evaluate this expectation” that children will be returned to their home country.

Roberts, who had earlier expressed concern about the possibility of delays arising from the consideration of risk-reduction measures, noted that the convention doesn’t say anything about risk-reduction measures at all. Instead, he stressed, it merely indicates that a trial judge can decline to return a child who would face a grave risk of harm in her own country.

Just as he had with King, Breyer pressed Min to articulate what rule the Supreme Court should establish. Min stressed that even if the trial court is required to consider risk-reduction measures, its inquiry can be a relatively limited one. He noted that “there is a distinction between consideration and implementation of ameliorative measures.” And a court can consider risk-reduction measures very quickly – indeed, almost instantaneously, Min suggested. Moreover, he added, the 2nd Circuit’s “case law is very clear that they have not remanded cases historically” simply because trial courts have not considered all possible risk-reduction measures.

Gorsuch then asked Min whether, under his rule, courts are required to consider risk-reduction measures that might allow the child’s return even if neither parent proposes them. Isn’t that, Gorsuch asked, “the fundamental problem with the 2nd Circuit’s approach” – that it “seems to suggest that the district court had to go out and investigate measures on its own”?

Min pushed back a little, countering that the court would have to consider “obvious, readily accessible available remedies” even if the parents did not necessarily suggest them. But in general, he suggested, the court would only have to consider risk-reduction measures proposed by the parents, and the burden would fall to the parent who is opposing the child’s return to “overcome the presumption that the courts in the system are capable of protecting children.” And considering risk-reduction measures, Min added, wouldn’t take any extra time regardless of whether the consideration was mandatory or discretionary.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett outlined a road map for a possible solution. “Would it really be so bad,” she asked Liu, “if we send it back, offer something in the way of guidance, even if it is simply to say, yes, district courts have discretion that should be exercised consistent with” federal law and the convention. However, she continued, “given these concerns and how often they are present in domestic violence cases, use caution before going forward with them in that context?”

A decision in the case is expected by summer.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.