TRIBUTE TO JUSTICE BREYER

Learning from Justice Breyer’s vision for solving problems in a pluralistic nation

on Feb 4, 2022 at 12:36 pm

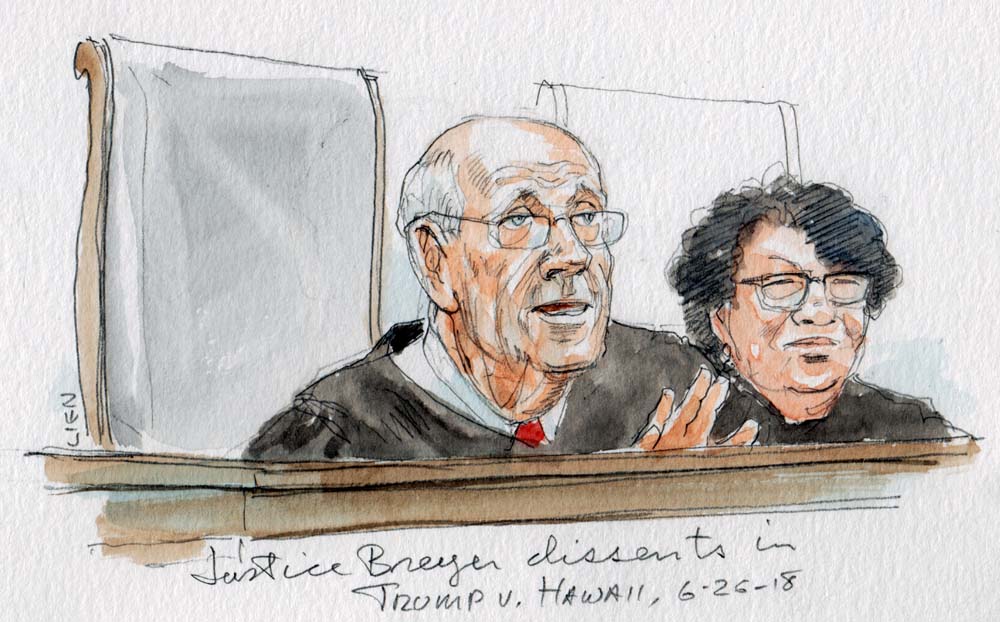

This article is part of a series of tributes on the career of Justice Stephen Breyer.

Carolyn Shapiro is a professor of law and founder and co-director of the Institute on the Supreme Court of the United States at Chicago-Kent College of Law, and she is of counsel at Schnapper-Casteras PLLC. She clerked for Breyer during the 1996-97 term.

One of the pleasures of reading and watching the many tributes to Justice Breyer in recent days has been to see, over and over, his law clerks, colleagues, and others describe his commitment to democracy, to the institutions of government, to the rule of law, and to finding common ground. These qualities were on full display during his speech at the White House last week, including when (to my delight!) he quoted his mother:

[T]his is a complicated country. More than 330 million people. My mother used to say, it’s every race, it’s every religion — and she would emphasize this — it’s every point of view possible. It’s a kind of miracle when you sit there and see all those people in front of you. People that are so different in what they think. And yet they decided to help solve their major differences under law.

Justice Breyer’s commitment to our ability to solve our “major differences under law” manifests not only in his speeches, conversations with students, and interactions with colleagues. It’s right there in his opinions.

Take his dissent in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, which has come up repeatedly in discussions of his tenure. In that case, Justice Breyer insisted that there is a significant difference between race consciousness in the service of segregation and subjugation and race consciousness used to combat racial isolation. He rejected the majority’s conclusion striking down the school districts’ modest use of race consciousness to maintain integrated schools.

But in so many ways, his dissent also exemplifies his deep commitment to and optimism about the democratic process. Rejecting the rigid certitude of some in the majority, Justice Breyer explained (my emphasis):

I do not claim to know how best to stop harmful discrimination; how best to create a society that includes all Americans; how best to overcome our serious problems of increasing de facto segregation, troubled inner-city schooling, and poverty correlated with race. But, as a judge, I do know that the Constitution does not authorize judges to dictate solutions to these problems. Rather, the Constitution creates a democratic political system through which the people themselves must together find answers.

Not only did Justice Breyer insist that the court respect good-faith efforts to solve challenging problems through the democratic process, he also saw the school districts’ efforts as essential to maintaining our democracy. The school districts’ race consciousness was justified by three compelling interests, he said. The first was remedying longstanding de facto segregation and the second, providing children the educational benefits of integrated schools. But there was a third, broader, and more fundamentally democratic justification:

Third, there is a democratic element: an interest in producing an educational environment that reflects the “pluralistic society” in which our children will live. … It is an interest in helping our children learn to work and play together with children of different racial backgrounds. It is an interest in teaching children to engage in the kind of cooperation among Americans of all races that is necessary to make a land of 300 million people one Nation.

For Justice Breyer, democracy can help our diverse nation solve our problems – but it does not happen magically. It requires education, effort, and the willingness to listen to and learn from people different from ourselves.

We can see these commitments in action in Van Orden v. Perry. (I haven’t seen Van Orden get as much attention as Parents Involved, perhaps because in Van Orden, Justice Breyer provided the fifth vote for a “conservative” result – to uphold a Ten Commandments display on the Texas State Capitol grounds.)

Justice Breyer’s opinion concurring in the judgment in Van Orden started by noting the “basic purposes” of the First Amendment’s religion clauses, which he said are to “assure the fullest possible scope of religious liberty and tolerance for all” and to “avoid that divisiveness based upon religion that promotes social conflict.” He rejected “absolutism,” and in fact, the same day, he joined the Van Orden dissenters in striking down a different Ten Commandments monument.

In deciding whether the Van Orden display violated the First Amendment, Justice Breyer looked at whether it was in fact divisive. He discussed the secular and historical purposes and origins of the display; he explained that it was in a setting with a number of other undeniably secular monuments. But he gave “determinative” weight to the fact that the monument had been there for 40 years apparently without controversy. “Those 40 years suggest that the public visiting the capitol grounds has considered the religious aspect of the tablets’ message as part of what is a broader moral and historical message reflective of a cultural heritage.” He concluded that the court should embrace and promote that tolerant and accepting perspective as consistent with the First Amendment’s religion clauses.

If you had asked me before the case was decided, I suspect I would have sided with the dissenters. But Justice Breyer’s opinion persuades me. It reminds us that a functioning democracy in our diverse, pluralistic society – with “every race, … every religion, … every point of view possible” – requires tolerance, flexibility, and generosity of spirit. These qualities are in unfortunately short supply in our public life these days. May we all learn from Justice Breyer’s example.