Argument preview: Justices to hear second set of arguments on reservation status of eastern Oklahoma

on Apr 30, 2020 at 11:30 am

McGirt v. Oklahoma will bring the justices a pronounced sense of déjà vu, as they hear argument for the second time in two years about whether the eastern half of Oklahoma is an Indian reservation.

Given the obscure historical problems that dominate Indian law, the doctrinal terrain of the issue is remarkably clear-cut. Ordinarily, status of land as an Indian reservation brings with it a variety of consequences that are important for regulatory and criminal enforcement. Among other things, the Major Crimes Act allocates responsibility for prosecuting major crimes committed by Indians on a reservation to the federal government rather than state authorities. Traditionally, the Supreme Court decides whether land is a reservation first by asking whether the land ever was a reservation (usually a pretty simple question), and then by asking whether a federal statute explicitly ends the land’s status as a reservation.

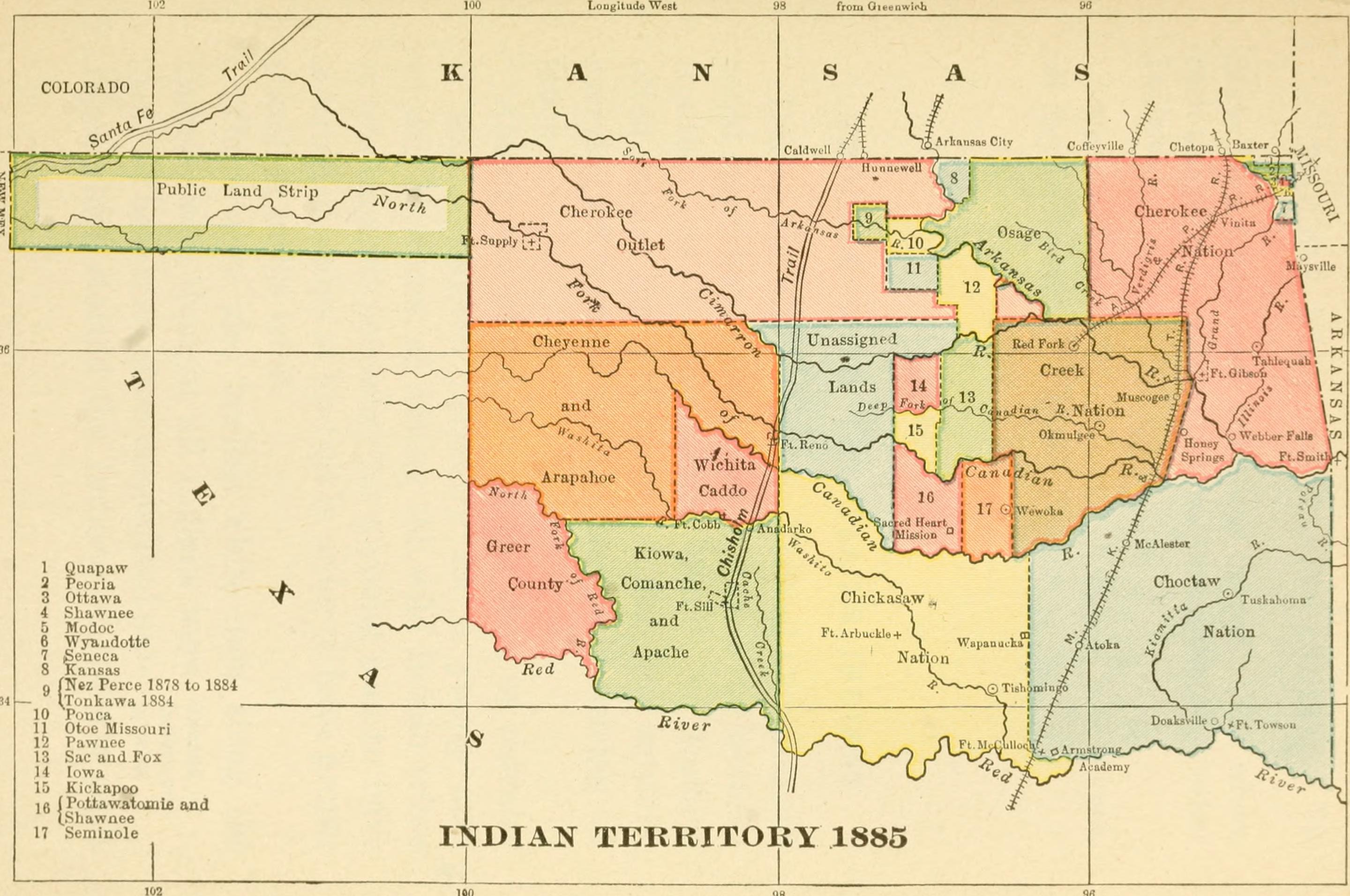

Application of those rules to the present situation seems uncomplicated at first glance. The Creek Nation was one of the Five Civilized Tribes forcibly and brutally relocated in the 1830s from Georgia, Alabama and Florida to a large Indian Territory that included what is now the eastern half of Oklahoma. It has long been understood that the Indian Territory was a reservation at least until 1906, when the state of Oklahoma was formed. State and federal authorities since 1906 have operated on the assumption that the land lost its reservation status at that time, though it is not easy to identify a federal statute terminating that status with anywhere near the level of clarity the court has sought in previous cases. Accordingly, it is fair to say that a straightforward application of the court’s prior cases readily would support the conclusion that the land in question remains an Indian reservation to this day.

Enter Carpenter v. Murphy, later retitled Sharp v. Murphy after a change in personnel at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, a case involving the conviction by the state of Oklahoma of a member of the Creek Nation named Patrick Dwayne Murphy for a murder committed in the eastern part of the state. When a lower court vacated Murphy’s conviction on the theory that eastern Oklahoma remains a reservation, and that Oklahoma therefore did not have jurisdiction to prosecute the case, the Supreme Court granted review and heard oral argument on that question in November of 2018. As summarized in my post at the time, several justices reacted with incredulity to the idea that the entirety of eastern Oklahoma (including all of Tulsa) could be an Indian reservation, raising concerns about the consequences of such an outcome for criminal justice, taxation and regulatory authority in that part of the state. For example, the chief justice wondered at length about problems such as the possibility that the Creek Nation might choose to ban the sale of alcohol within its reservation. The attorney representing the state ended the argument by emphasizing that a ruling for Murphy would call into question the validity of numerous state criminal convictions for numerous murders, rapes and crimes against children.

The first sign that the justices may have been struggling to resolve the case came a few weeks after the argument, when they called for more briefing as to whether Oklahoma might retain prosecutorial authority over crimes involving Indians in eastern Oklahoma even if that area remains an Indian reservation. Those briefs were filed over the winter, but no decision was forthcoming. Finally, on the last day of the term in June of 2019, they set the case for re-argument in October Term 2019.

Strangely, though, when the argument calendars for the fall of 2019 appeared, they did not include an argument for Murphy. Rather, the justices eventually granted review in McGirt, in which the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals upheld the conviction of Jimcy McGirt, a member of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, for sexual assault allegedly committed within the 1866 boundaries of the Creek reservation. One likely explanation is that Justice Neil Gorsuch was recused in Murphy, apparently because he participated in the case as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, so only eight justices were available to resolve that case. In contrast, a bench of nine can hear argument in McGirt, a significant distinction if the justices deadlocked 4-4 in Murphy. McGirt was set for argument in the ill-fated March session, cancelled because of COVID-19. Now it has been included in the small group of cases from March and April that will be argued remotely in May.

Understanding how we got to this point provides a good glimpse of the path between Scylla and Charybdis the justices will seek to traverse when they hear argument in McGirt. On the one side lies a strong doctrinal argument for recognizing continuing reservation status of a tribe victimized by one of the most shameful incidents in our nation’s history. On the other side lie the sobering practical ramifications of upending a century of prosecutorial and regulatory understandings about what would be the most populous Indian reservation in America, with 1.8 million inhabitants.

The other important development is that Oklahoma has changed its position on an issue central to both Murphy and McGirt. Although it agreed last year in Murphy that the Indian Territory originally was a reservation and argued that Congress disestablished the reservation when it formed Oklahoma, the state now maintains that the Indian Territory was never a reservation in the first place. Rather, Oklahoma argues, the former land of the Creek Nation was a separate type of enclave known as a “dependent Indian community,” which passed into statehood without ever attaining reservation status. It is difficult to assess how seriously the justices will take that argument. In the typical case, a last-minute shift of position would be understood by all as a sign of weakness, and we would expect the justices to afford little or no credibility to the late-discovered argument. On the other hand, the justices might be searching for a lifeline that would avoid the consequences of imposing reservation status on eastern Oklahoma. I expect we will know a lot more after the oral argument about the extent to which the justices are willing to explore Oklahoma’s newfound position.