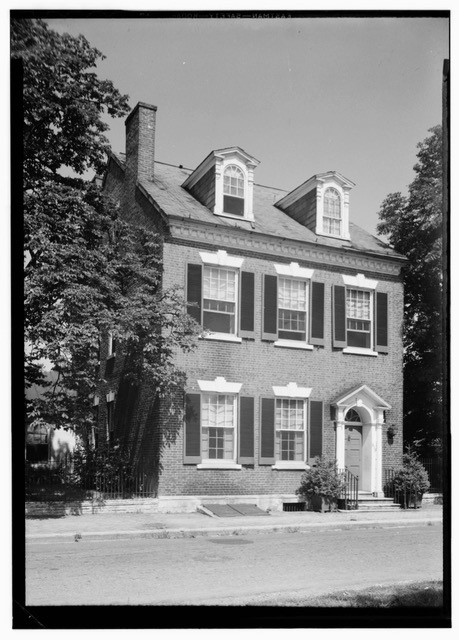

Justice Black’s house at center of Alexandria dispute

on May 9, 2019 at 5:12 pm

From 1939 until his death in 1971, Justice Hugo Black lived in Alexandria, Virginia, at 619 S. Lee Street.

On Tuesday, the Alexandria City Council will consider a proposal by the current residents to work on parts of the existing structure and build additions in the property’s extensive gardens and open space.

The issue comes to the city council on appeal by the Historic Alexandria Foundation, together with other interested groups and citizens, from the Old and Historic District Board of Architectural Review, which approved the plans. The foundation maintains that, among other violations, the homeowners’ plans are inconsistent with the preservation easement Black imposed on the property under Virginia’s Open Spaces Land Act.

Whatever happens with 619 S. Lee Street, the moment shines a small light on Black’s domestic life.

Supreme Court scholar A.E. Dick Howard, a Black clerk for two terms from 1962 to 1964 and the Warner-Booker Distinguished Professor of International Law at the University of Virginia School of Law, wrote a letter to the Alexandria mayor and members of the city council, urging them to reject the plans.

“I have vivid recollections of Justice Black’s house,” Howard writes. He recounts spending hours, “especially on weekends,” at 619 S. Lee Street, where he and the justice “compared notes on petitions for certiorari, worked on drafts of his opinions, and had long conversations about law and life.”

“Sometimes we worked in his library,” Howard adds, one “especially rich in history – Polybius and Tacitus, Gibbon and Carlyle, the teachings of Whig history.” He describes Black as “[o]ne of the best-read Justices in the history of the Supreme Court.” (Black’s collection, consisting of over 1,000 volumes, is at the Bounds Law Library at the University of Alabama School of Law, from which he graduated in 1906.)

“In good weather, we would sit in his garden,” Howard continues. “In a town where open space was at a premium, Justice Black took special pride and pleasure in the garden, tennis court, and greensward.”

“Dick,” the justice used to remark to his clerk, “this place is a little piece of Eden.”

“Here was a Justice who left his imprint across the board in important areas of the law, especially in cases interpreting and applying the Constitution,” Howard writes in praise of Black’s jurisprudence. Howard also singles out seven landmark opinions, characterizing them as follows:

- Gideon v. Wainwright, “holding that in felony cases a state must provide counsel to a defendant who is unable to hire one”

- Everson v. Board of Education, “holding that the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause applied to the states”

- Torcaso v. Watkins, “holding that religious tests may not be used to decide who holds public office”

- Engel v. Vitale, “declaring that the state may not compel the recitation of a state-composed prayer in schools”

- Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, “ordering the County to reopen and fund public schools which had been closed during the era of “Massive Resistance’ in Virginia” to Brown v. Board of Education, which Black had joined

- Wesberry v. Sanders, “holding the Constitution’s command that the House of Representatives be elected ‘by the People’ requires that congressional districts be equal in population”

- New York Times v. United States, a concurring opinion in the Pentagon Papers case that’s a “classic exposition of why the free flow of ideas and information is a staple of a free society”

Although in his letter Howard does not mention Black’s authorship of Korematsu v. United States, allowing the forced internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, he has stated that the opinion is “unquestionably an indelible stain on the jurist’s career. But, however bad that opinion, it does not alter Black’s status as one of the great justices in the history of the Supreme Court.” (Another former Black clerk, John Kester, notes in his own letter to the mayor that Korematsu “also established for the first time that ‘all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect’ and ‘courts must subject them to the most rigid scrutiny.’”)

Howard claims that Black “stands with figures like John Marshall, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Louis Brandeis, and William Brennan who have genuinely shaped the Court’s jurisprudence.” The homes of the first three of those justices are all National Historic Landmarks, as are those of at least six other justices:

- Justice Louis Brandeis (Chatham, Massachusetts)

- Justice David Davis (Bloomington, Illinois)

- Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (Beverly, Massachusetts)

- Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes (Washington, D.C.)

- Chief Justice John Marshall (Richmond, Virginia)

- Justice John Rutledge (Charleston, South Carolina)

- Justice Joseph Story (Salem, Massachusetts)

- Chief Justice William Howard Taft (Cincinnati, Ohio)

- Chief Justice Edward Douglass White (Lafourche Parish, Louisiana)