Argument preview: Justices to consider stale claims in consumer bankruptcies

on Jan 10, 2017 at 2:05 pm

Next Tuesday’s argument in Midland Funding v. Johnson brings the justices to the sordid world of consumer debt collection. In that world, a small group of relatively large “debt buyers” have come to amass portfolios that include the past-due obligations of millions of consumers, representing billions of dollars of unpaid obligations. The problem comes from the reality that a large share of that debt is not legally collectible because the statute of limitations (typically six years) has expired. The debt has value (at least to the extent of several cents on the dollar) because of the possibility that the debt buyer ultimately will persuade the consumer to make some payment on the obligation even though the opportunity for legal enforcement has passed.

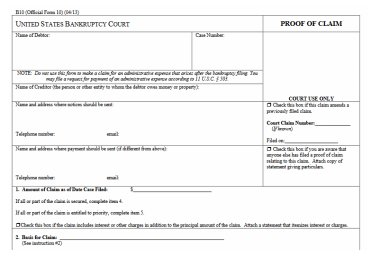

Over the last decade, an increasingly common strategy for those debt buyers has been to file proofs of claim for that debt in the bankruptcy proceedings of the insolvent consumer debtors. Taking advantage of modern information technology, those debt buyers have been much more vigilant and assiduous than were past creditors in presenting claims for the time-barred obligations, resulting in a massive increase in the volume of claims filed in routine consumer bankruptcies.

The legal problem for the justices is a classic one – analyzing the overlap between the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, which regulates the activity of the debt buyers, and the Bankruptcy Code, which defines the process in which the problematic upsurge of filings has arisen. For its part, the FDCPA prevents creditors from “us[ing] any false, deceptive, or misleading representation or means in connection with the collection of any debt.” Lower courts routinely have held that debt collectors violate that ban when they file suit to collect a debt that plainly is barred by a statute of limitations.

For their part, the debt buyers argue that the Bankruptcy Code validates everything they do in the bankruptcy process. Their claim filings are not false in any way: The filings accurately note the date of the relevant credit transactions, making it in most cases easy to see if the transactions are beyond the statute of limitations. Moreover, because the code’s definition of “claim” is so broad, it is hard to argue that even a time-barred debt falls outside the process. Thus, the debt buyers contend, filing a claim in the bankruptcy process should be treated differently under the FDCPA than filing suit. Essentially, they argue that the bankruptcy process provides debtors all the protections they need and that it makes no sense to impose FDCPA sanctions on creditors for honest participation in the statutory process for final resolution of the debts of insolvent consumers.

The logic of the debt buyers’ argument has considerable appeal, especially in its delineation of separate domains for the FDCPA and the Bankruptcy Code. But the emphasis of the debtor, Aleida Johnson, and the “friends of the court” who have filed briefs on her behalf on the practical realities of consumer bankruptcy well might give the justices pause. Under the code, a creditor’s proof of claim is presumed valid; claims are disallowed only if a trustee expends the time, effort, and resources necessary to file an objection, persuade the court of its merit, and obtain an order disallowing the claim. Unrepresented debtors (a common phenomenon) rarely will succeed in that process, and trustees acting on their behalf face resource constraints that make it a challenge to interpose routine objections even to the most flagrantly untimely claims. The truth is, the only reason it makes economic sense for the creditors to take the time to file claims that plainly are stale is the reality that they often receive payments on those claims.

For me, the key thing to watch at the argument will be what the justices think about the action of filing a claim. The last time the justices heard an FDCPA case (last term’s Sheriff v. Gillie), they were deeply skeptical of a broad application of the FDCPA’s proscription on “misleading” communications. The task for the debt buyers here will be to persuade the justices that filing a truthful proof of claim is similarly innocuous.