Troy Davis and the appeal puzzle

on Oct 22, 2010 at 12:22 pm

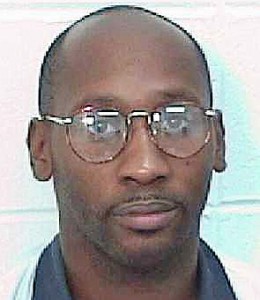

The Supreme Court has taken a special interest in the case of a Georgia death-row inmate, Troy Anthony Davis, using an unusual source of power to give him a new chance to press his claim that he is innocent, and that someone else killed a Savannah policeman 21 years ago. But, in the process, the Court appears to have created a puzzle: now that a federal judge has ruled against Davis’s plea of innocence, where does he appeal next? There appears to be no clear answer.

The Supreme Court has taken a special interest in the case of a Georgia death-row inmate, Troy Anthony Davis, using an unusual source of power to give him a new chance to press his claim that he is innocent, and that someone else killed a Savannah policeman 21 years ago. But, in the process, the Court appears to have created a puzzle: now that a federal judge has ruled against Davis’s plea of innocence, where does he appeal next? There appears to be no clear answer.

On Tuesday, the U.S. District Court in Georgia sent a letter to the Supreme Court, delivering a copy of an order District Judge William T. Moore, Jr., had issued on Oct. 8, finding that Davis may only appeal to the Supreme Court — not to the Eleventh Circuit Court — to pursue his case further. The Tuesday letter is under seal, but Judge Moore’s six-page order can be read here. In August, Judge Moore, reviewing the case on orders directly from the Supreme Court, had ruled that Davis is not innocent. (That ruling is discussed in this post.)

Davis was convicted and sentenced to death for the 1989 shooting death of Savannah Officer Mark Allen MacPhail, while the policeman was working a part-time security job outside a fast-food restaurant in the Georgia city. In recent years, seven of the prosecution’s key witnesses at Davis’s trial had recanted what they said at the trial, and several individuals have suggested that the prosecution’s chief witness actually did the killing.

But, by April of last year, Davis had run out of legal options in the lower courts, when the Eleventh Circuit refused to let him file a new habeas challenge in those courts. So, Davis’s lawyers turned to the Supreme Court, asking the Justices to issue what is formally called an “original” writ of habeas corpus — that is, one that the Court itself would issue with no involvement by a lower court.  The Court had not done so in nearly 50 years, so it was a long shot.

However, on August 17 of last year, over the dissent of two Justices (and with one Justice not participating), the Court transferred Davis’s petition to Judge Moore’s District Court “for hearing and determination.” The Court’s order said that the judge was to “receive testimony and make findings of fact as to whether evidence that could not have been obtained at the time of trial clearly establishes” Davis’s innocence.  Judge Moore carried out that order, holding a hearing in June, with new witnesses offered by Davis’s lawyers, and soliciting new briefs on how one might prove innocence. At the end of the process, the judge on August 24 issued a 172-page decision concluding that Davis “is not innocent.”

In the course of his ruling, the judge expressed some puzzlement about what kind of authority he was exercising. He suggested, in a footnote, that since the case had come to him directly from the Supreme Court, he was functioning “as a magistrate for the Supreme Court, which suggests appeal of this order would be directly to the Supreme Court.” He added, however, that he “has been unable to locate any legal precedent or legislative history on point.” Even so, he said, he was sending a copy of his decision to the Justices.

Davis’s lawyers soon filed two formal notices of appeal — one to the Eleventh Circuit (found here) and one to the Supreme Court (found here). The lawyers indicated that they had done so because they doubted that Supreme Court rules or precedent would allow a new appeal to the Justices. Separately, his attorneys asked Judge Moore to issue a “certificate of appealability” — a necessary document if the appeal were to go to the Eleventh Circuit. (That document is here.)

In denying that application on Oct. 8, Judge Moore concluded that it would violate federal habeas law for the case to go to the Eleventh Circuit, since that court had previously refused to allow Davis to pursue a new habeas claim. In fact, the judge said, if the Supreme Court were acting in its appellate capacity when it ordered a new review of Davis’s case, it would not have had the authority to do so because that route was not open to Davis. Since the Supreme Court was using its original jurisdiction authority, the judge said, the Justices had taken the only option that Davis and his counsel had left to them.

Accepting Davis’s argument that an appeal to the Eleventh Circuit is now open to him, the judge said, “would require this Court to believe that the Supreme Court can implicitly act in a manner expressly forbidden by Congress. The Court is unprepared to make such a ruling.” Thus, the judge decided, no appeal remained open to the Eleventh Circuit, and no certificate would be issued to permit such an appeal.  Any new review of Davis’s original habeas case, the judge said, “must be conducted by the Supreme Court.”

At this point, it is unclear just what procedural route Davis’s lawyers would take to get the case back to the Supreme Court. The options appear to be simply to notify the Court that the judge’s ruling on the habeas petition is now back before the Justices for review on the merits, or to file a certiorari petition asking permission to appeal to the Court, or to file a “jurisdictional statement” suggesting that the case formally is being appealed.

The Court’s rules do not appear to settle that procedural question. It would be up to the Court, then, to make up its own mind on how — or even whether — to go forward.