Argument analysis: Moral responsibility for death sentences

on Oct 13, 2015 at 7:27 pm

Analysis

In the nearly four decades since the Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty as constitutional, the Justices and lower courts have created an unusually complex, interwoven set of legal processes for capital cases. One result of that is that it sometimes is very difficult to pinpoint where, in the system, lies the moral responsibility for sending someone to death row. It became quite clear on Tuesday, though, that the Court wants that responsibility to be with the people who sit on juries.

As the Court, hearing Hurst v. Florida, talked its way through the Florida death penalty system, which uniquely among thirty-one states goes far to pare down the role of the jury, it took a great deal of discussion of the intricacies of that system before the moral question arose. But it did arise.

The lawyer for death-row inmate Timothy Lee Hurst stayed close to one quite simple theme: Florida leaves juries with almost no sense that they are making the ultimate choice. The lawyer for the state, by contrast, had to make his way through a wide array of technical questions serving mainly to illustrate how little can be known about the choices the jurors did make in any given case.

The case is about a brutal murder in a fast-food restaurant in Pensacola, but it reaches the Court as a clear-cut test of what the Justices had in mind in the 2002 decision in Ring v. Arizona. That ruling seemingly enhanced the role of the jury in capital punishment cases, assigning them the crucial task of deciding the facts that make a person accused of murder eligible to be put to death.

The Florida Supreme Court has taken the position that the Ring decision does not even apply to its death penalty system — a position that its lawyer — state Solicitor General Allen Winsor — did not repeat on Tuesday, even as he argued that the system fully satisfies that ruling. It would be Winsor who would, before the hearing ended, face the hardest questions about moral responsibility.

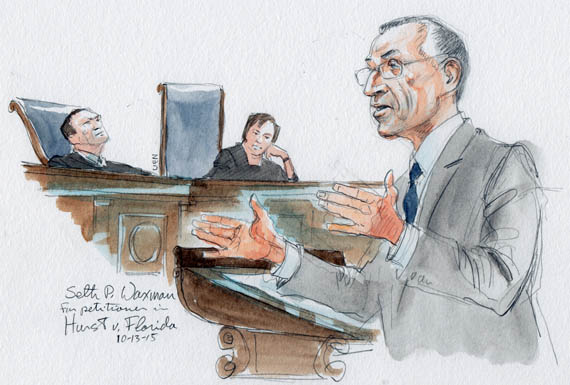

Hurst’s lawyer, Washington, D.C., attorney Seth P. Waxman (a former U.S. Solicitor General), left no doubt from the outset that he was aiming to put Winsor on the defensive on the jury question. “Under Florida law,” he began, “Timothy Lee Hurst will go to his death despite the fact that a judge, not a jury, made the factual finding that rendered him eligible for death.”

Under Florida law, no one can be put to death unless there is a finding of one “aggravating factor” — usually, some fact about the crime or the way it was committed that would justify the ultimate penalty. The jury, Waxman noted, only offers an advisory opinion to the judge about such factors, and then suggests either life or death.

Waxman quoted from Florida law, noting that the judge makes the crucial finding of aggravating factors “independently, and, quote, ‘notwithstanding the jury’s recommendation as to sentence.'” For most of his argument, he never strayed far from that point or from his secondary point that Florida is the only state to do it in that way. The Justices, as usual, tried a few hypotheticals to test the way the Florida arrangement actually works, but the sidelining of the jury was almost always a part of Waxman’s answers.

From the moment that Florida’s Winsor took the lectern, arguing at first that his state’s system was constitutional before and after Ring v. Arizona, he was almost constantly bombarded with probing questions about what juries actually did under that system. Justice Sonia Sotomayor was perhaps the most aggressive questioner.

Winsor sought to show that the task given to Florida juries was a serious one, but the questions from the bench continued to suggest that, no matter what the jury did or recommended, it could be overridden by the final choices that are assigned to the judge. At some points, it appeared that the state’s lawyer was making at least some concessions that part of the system would not satisfy the Ring precedent.

For a time, it seemed that the whole of Winsor’s time would be taken by talk of the technical details of the interaction between jury and judge. But then Justice Antonin Scalia moved into the center of the exchanges. “Is it clear to the jury,” he asked simply, “that they are the last word on whether an aggravator exists or not?” It was the moral question in the form of a process inquiry.

The state’s lawyer answered that the jury would have had to find an aggravating factor for there to be any chance of a death sentence. But Scalia countered: “They’re also told that the judge is ultimately going to decide whether your recommendation stands, or not.” Winsor started to answer, but Scalia interrupted: “But shouldn’t it be clear to the jury that their determination of whether an aggravator exists or not is final? Shouldn’t that be clear?”

In a moment, Scalia made his underlying point clearer: “I’m talking about what responsibility the jury feels. If the jury knows that…., if we do find an aggravator, it must be accepted. That’s a lot more responsibility than, just, you know, if you find an aggravator and you weigh it and provide for the death penalty, the judge is going to review it anyway.”

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy soon used a series of questions about hypotheticals to make the same point.

It was no surprise that, when Waxman rose to offer a rebuttal to Winsor, he immediately referred to Scalia’s questions about moral responsibility. He commented: “Was the jury told — and doesn’t a jury have to be told — that as to death eligibility, the element of the crime of capital murder, that it makes the decision? The answer is: it does have to be told that. It certainly can’t be told the opposite, and it absolutely was not told that. It was told over and over, consistent with the statute, that its decision was purely advisory.”