Ask the author: Floyd Abrams & his fighting faith

on May 17, 2013 at 4:05 pm

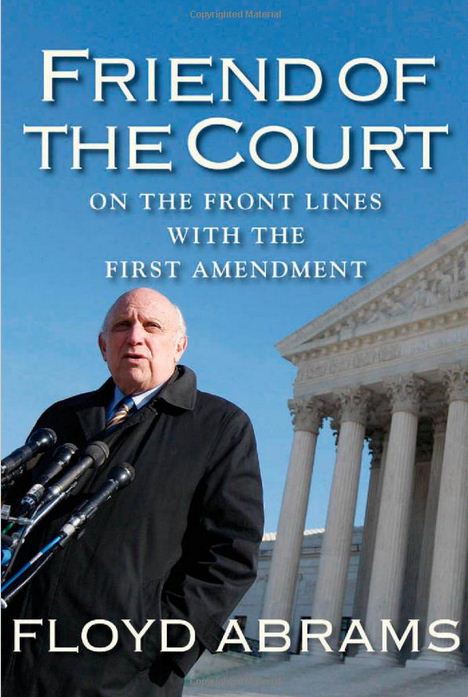

The following is a series of questions posed to Floyd Abrams by Ronald Collins on the occasion of the publication of Abrams’s new book, Friend of the Court: On the Front Lines with the First Amendment (Yale University Press, 2013).

Welcome, Floyd. Thank you for taking the time to participate in this Question and Answer exchange for our readers. And congratulations on the publication of your second book.

Question:

You’re seventy-six years old and still quite active in litigating First Amendment cases. And now another book about your life in the law, the law of the First Amendment, that is. Would it be fair to say that you love your work?

Answer:

Yes. I’ve been very lucky in a lot of ways — my family, my law firm, and my good fortune in being able to devote a good deal of my professional and personal time to seeking to protect and expand First Amendment principles.

Question:

The title and subtitle of your latest book suggest that you are venturing, on the one hand, to help the Court better understand the First Amendment while, on the other hand, battling those who would undermine the First Amendment. Can you say a few words about your roles as educator and combatant?

Answer:

I think it is possible to play both roles — educator and litigator. Indeed, some litigation, particularly on constitutional topics, necessarily and inevitably educates and sometimes even enlightens. But the role of a litigator, after all, is to seek to prevail — the litigation equivalent of Justice William Brennan telling his law clerks that the most important thing for a member of the Court is to know how to count to five. I also, and independently from my appearances in courts, have given a lot of speeches, written a lot of articles and engaged in a lot of debates, many of which are set forth in Friend of the Court. It is in those documents, far more than what I say as counsel, that my own views are set forth.

Question:

In the Introduction to Friend of the Court you mention the gulf between the First Amendment bar and those who in the legal academy who write about the First Amendment. Share with us some of your thoughts on that subject and how law schools train their students.

Answer:

My core criticism of the legal academy, at least in its First Amendment teaching, is not that it’s too “academic”; it’s that it doesn’t take the First Amendment — at least as I understand it — seriously enough. In my book, I quote twice from a passage of Isaiah Berlin in which he observed that “[e]verything is what it is: liberty is liberty, not equality or fairness or justice or culture, or human happiness or a quiet conscience.” In this country, I would substitute the words “First Amendment” for “liberty.” That does not mean that equality and other significant values necessarily lack constitutional or other legal support; it does mean that when we speak of the First Amendment, we should be speaking of individual liberty and not of a watered-down version drafted to accommodate those other interests — ones which can generally be protected without intruding into areas protected by the First Amendment.

Question:

The legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin, who died recently, admonished: “we must take care not to convert the First Amendment from a matter of principle to a pointless mantra that subverts rather than sustains democracy.” What is your answer to that?

Answer:

Ronald Dworkin was a great student and teacher of both philosophy and law and we should be grateful that he has left so significant a body of work for us to continue to learn from. But I think he erred greatly in maintaining that First Amendment cases should be decided on the basis of our view — or the Supreme Court’s view — of whether or not the speech at issue in a case advances “democracy.” That was one basis for his disapproval of the Citizens United ruling.

My view is that suppression of speech, particularly but not exclusively political speech, is inconsistent with what the First Amendment is most clearly and importantly about. That does not make the First Amendment a “pointless mantra”; it is the point of the First Amendment to prevent government from determining who can speak and what is worth saying.

Question:

If you can forgive my indelicacy, how do you respond to the charge that you do the bidding for big-money corporate America? You stand with them, so the indictment goes, on copyright law, on campaign financing, and on advertising, even tobacco advertising! By that measure, one might dare to ask the “Devil’s advocate”: “Have you no conscience, sir?” When you get such questions, as I trust you do, how do you reply?

Answer:

I reply by saying that I have spent a good deal of my professional life representing corporations, usually with no critical response by those who are offended at the identity of others of my clients. The corporations my critics seem to like (or forgive me for representing) publish newspapers, broadcast on television, own museums and the like. The ones they take offense about are more purely commercial and thus, I suppose, less deserving in the view of these critics of First Amendment protection.

I accept none of this for three reasons. First, I do not believe the First Amendment should be limited to particular classes of speakers. Second, I do not believe the First Amendment protects speakers as much as it protects speech — regardless of its source. Third, I am a lawyer who is willing and indeed pleased to represent a wide range of clients with a wide range of problems; that is, after all, what lawyers do.

Question:

Thirty years ago you wrote a piece in The New York Times Magazine (reproduced in your book) expressing serious concerns about the government’s efforts to control information. In McBurney v. Young, decided a few weeks ago, a unanimous Supreme Court, in an opinion by Justice Samuel Alito, declared: “This Court has repeatedly made clear that there is no constitutional right to obtain all the information provided by FOIA laws. . . . It certainly cannot be said that such a broad right has ‘at all times, been enjoyed by the citizens of the several states which compose this Union, from the time of their becoming free, independent, and sovereign.’” The Court also added that no such right was recognized under the common law, and early American history does not support that notion, either. Moreover, the current administration, like its predecessors, seems bent on controlling more and more information. What is your reply to all of this?

Answer:

I do not believe the First Amendment itself requires the government to disclose much in the way of information. Looking at the issue broadly, I agree with Justice Potter Stewart that the First Amendment is neither an Official Secrets Act nor a Freedom of Information Act. That said, I do believe that the government should be far more transparent than it is, that it should release far more information than it does and that there is a continuing problem of vast over-classification by the government.

Question:

In Friend of the Court you write a lot about various attacks on the press, both historical and current. I trust you saw the May 13, 2013 AP story in which it is alleged that “the government seized . . . records for more than twenty separate telephone lines assigned to AP and its journalists in April and May of 2012.” Are you familiar with this and do you have any comment on it?

Answer:

The Department of Justice’s action in obtaining vast amounts of telephone records of the AP at multiple sites for a two-month period is deeply disturbing. I have no reason to doubt the good faith of the government; the leak was obviously about highly sensitive matters. But I can think of no good reason why the DOJ could not have conferred with the AP and ultimately let the courts decide the issue, if judicial action was sought by either side. From my perspective, what occurred is not different conceptually from the FBI sending agents into the AP and demanding the immediate turnover of its telephone records.

The inhibiting effect — the word “chilling” has become a one-word cliché but it is applicable here — of this sort of behavior by the DOJ is obvious here — on the press, on potential whistle-blowers, and the like. And I cannot give the DOJ or this administration the benefit of the doubt: there have been too many leak investigations, too zealous an approach to them, too little attention paid to the dangers in the government invading a newsroom.

Question:

You are on record as being a staunch defender of the holding in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010). You devote an entire chapter to it in your book. Last August, President Obama expressed an oppositional sentiment: “Over the longer term, I think we need to seriously consider mobilizing a constitutional amendment process to overturn Citizens United.” How would you respond to the President?

Answer:

I would urge the President to review Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinion for the Court in Citizens United. I would ask him what his answer is to Justice Kennedy’s three hypothetical questions in that case: “The Sierra Club runs an ad, within the crucial phase of 60 days before the general election, that exhorts the public to disapprove of a congressman who favors logging in national forests; the National Rifle Association publishes a book urging the public to vote for the challenger because the incumbent U.S. Senator supports a handgun ban; and the American Civil Liberties Union creates a web site telling the public to vote for a presidential candidate in light of that candidate’s defense of free speech. All that advocacy,” Justice Kennedy wrote, “would be criminal under the statute that the Supreme Court has now held to be unconstitutional.”

I would ask the President if he agreed that such speech could constitutionally be banned. And I would ask him if he really wants to be remembered as the first president who proposed a constitutional amendment narrowing the scope of the First Amendment.

Question:

In a recent interview on this blog, Marcia Coyle said this: “I have tremendous respect for Floyd Abrams. He is a hero to many of us in the media and I’m not surprised at all at his view of the case. He is a true champion of the First Amendment. I do think Citizens United was an aggressive decision. Citizens United had abandoned its facial challenge to the relevant provisions in the lower court so there was no record. The majority was ready to issue a decision overruling Austin and the provision in McCain-Feingold without briefing or argument, and there were narrower grounds on which to rule, alternatives offered even in Citizens United’s brief. Calling the decision aggressive does not necessarily mean that I thought it was wrong.”

Was Citizens United an “aggressive decision”? What is your reply to Ms. Coyle?

Answer:

Of course Citizens United was an aggressive opinion. So, as I pointed out in my oral argument in the case, was New York Times v. Sullivan. The Court did not have to go as far as it did. But as in Sullivan and too many other cases to cite here in which the Court concluded that a broad opinion was necessary, it provided one. I feel obliged to add that an awful lot of academics who seemed unconcerned at (and even celebrated) the breadth of many decisions of the Warren Court seem terribly preoccupied by the scope and procedural history of Citizens United.

Question:

You close your book with the following words: “Is it really too much to ask that those who claim they care about the First Amendment – everybody that is – stand in favor of free speech even when the speech at issue pains them ideologically?”

We as a nation have certainly made progress on that score. But do you really think we can make yet more progress? And what will it take for us to do so?

Answer:

It’s so hard to say. And in the so very polarized world in which we live today, it is hard to be optimistic. But we have to keep trying.

Question:

I hear you have another book in the works. True? What can you tell us about that?

Answer:

True. And I have nothing to say about it.